Unsurprisingly, Omung Jumar's biopic PM Narendra Modi split opinion among Indian audiences and critics after its eventual release last weekend - the film was forced to delay its original release by the Indian Electoral Commission so as not to risk influencing voters in the country's now completed general election.

The film is certainly polarising. For Modi fans, it’s a stirring tribute to a great leader. For opponents, it is jingoistic hagiography on a grand scale. It’s not hard to work out which side of the fence the film’s star Vivek Oberoi sits on – he seems in awe of the character he plays from the moment he speaks about the PM at this week’s launch event for the film in Abu Dhabi: “Doing this film was one of those occasions when the journey was more beautiful than the destination,” he says.

Oberoi on how he managed to look like Modi

Of course, not everyone shares Oberoi’s opinion of the film: even before the film had started shooting, the actor himself took criticism from supporters and opponents alike – Oberoi admits that many people questioned his casting, stating that he would never be able to successfully convince audiences he was the PM.

The star says he gladly took on the challenge, and even took a leaf out of Modi’s book when it came to his approach.

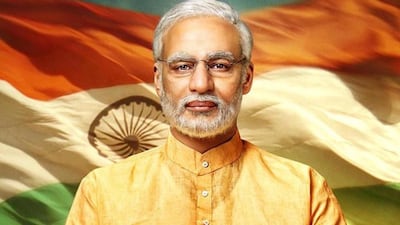

“We used lots of prosthetics to achieve the look, and the producers were saying we need to get someone in from Japan, the US, the UK. I said ‘No. It’s Modi – even the makeup has to be made in India,’” he reveals. “We had all Indian technicians. It was an eight-hour process with glue and silicon. You can’t move, eat, drink. The first time I got up after eight hours, I looked at myself long in the mirror and said ‘no it’s absolutely rubbish. Do it again.’”

Oberoi says it took 15 attempts to finally achieve the right look, but adds that all the hours and effort were worth it: “When people tell me that they went to the theatre and thought they were watching Modi on screen, that makes it all worthwhile for me,” he says. “It was a really emotional experience to watch people clapping and cheering. I’ve done 46 films in seven languages in my life and this is so special. It will leave an impression for rest of my life.”

Oberoi even went as far as cutting onion and garlic from his diet and rising each day at 4am to practice yoga to better get into the character of Modi. Indeed, his performance was one element of the film that received critical praise, though even critics who praised Oberoi himself were generally negative about the film’s status as a propaganda tool.

The Times of India's Renuka Vyavahare, for example, described the film as "lopsided," while The Indian Express' Shubhrata Das described it as "unabashed, unapologetic hagiography."

Oberoi refuses to take the reviews to heart: “Criticism usually bothers me, especially when you feel it’s unfair, but what I realised when I was researching this film is how much criticism Modi himself faced, and he never wavered from his focus. He kept going and he’s brought a new politics to India.”

Oberoi on what he respects most about Modi

“I’ve known him as a friend for a long time and it’s amazing that a man who hadn’t been to Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge or somewhere was talking about solar power years ago. No one was talking about solar at that time and he said ‘wait 10 years and it’ll be cheaper than coal and thermal energy.’ That’s what it’s become now. There’s energy independence for India, and this guy with no technical education background has become the face of the global solar alliance.”

It’s not only Modi’s prescient thoughts on solar power that seem to have caught Oberoi’s imagination. The oft-repeated, and equally disputed, story of Modi’s rise from a humble street urchin selling tea at the Vagnagar Railway Station in Gujarat to prime minister of the world’s largest democracy also has the star transfixed:

“In the film we press a button on a time machine and all of us get transported back to the 1950s or 60s and this little train that stops at one railway station and a small kid runs in and starts selling us tea from little clay pots. If anyone had said ‘one day that kid is going to be prime minister’ you’d say ‘no come on, not possible.’ But he made it possible purely on his merit, despite coming from a highly underprivileged background.”

Oberoi on the criticism towards the film

Indian PM Narendra Modi, who was re-elected to office last week, is, in common with his Western and Eastern counterparts Donald Trump and Rodriguo Duterte, a divisive figure.

His supporters find his populist stance and “India first” philosophy a rousing paean to a great nation. For his opponents, however, his nationalist tendencies and Hindu exceptionalism represent the Indian expression of a rising global tide of right-wing populism which presents an existential threat to liberal democracy.

And Oberoi insists that the criticisms aimed at the film have been purely political ones, not genuine criticism: “These are ideological reviews. Because their ideas don’t match with Modi's they decide to try and find something wrong with the film,” he insists.

“If people experience the truth, you can see the enjoyment coming out of them as they come out of the theatre having learned the truth about Modi. These reviewers are just purely ideological, because they hide behind a pseudo-liberal mask and try to find things to criticise. It’s a good film.”

Oberoi looks to another biopic about an Indian leader to further defend his own film from what he sees as unwarranted criticism. Richard Attenborough's 1982 classic Ghandi was one of the most successful films of the eighties, picking up 11 Oscar nominations and winning eight, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Oberoi notes that even that film had its doubters, however: "I think the greatest biopic ever made is Ghandi. It won every award going, but if you look at reviews from the time then were asking 'why you showed Ghandi as a great man? Why didn't you show him as a bad father?'"

He concludes: “Richard Attenborough gave the best response: ‘You saw a bad father. I saw the father of the nation.’ And this film is the same.”