He Named Me Malala

Director: Davis Guggenheim

Starring: Malala Yousafzai, Ziauddin Yousafzai

Three stars

UAE audiences finally get to see the much-awaited Image Nation-produced documentary, He Named Me Malala, when it hits cinemas Thursday November 5.

Directed by Oscar-winning documentary maker Davis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth; Waiting for Superman), the film tells the story of the now-18-year-old Malala Yousafzai – Pakistani activist, advocate for girls' education and youngest winner of the Nobel Peace Prize (2014) – who was shot in the head by the Taliban when she was 15.

The movie recounts the teenager’s ordeal, her recovery in a UK hospital (a UAE-provided hospital plane flew her from a Pakistani military hospital to a specialist unit in Birmingham), her tireless crusade to make education available to children all over the world, and her family’s efforts to settle into their new home after being granted asylum in England.

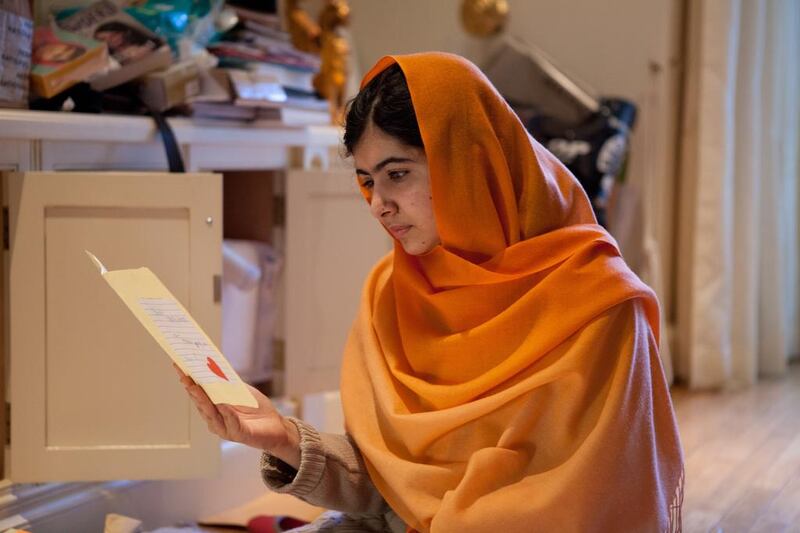

Guggenheim’s access to the family home shows us a side to Malala that is not often apparent in news reports. From the media portrayal of Malala, one could perhaps be forgiven for thinking she is some kind of miracle in her Swat Valley town.

But the film reveals that she is very much a product of her home environment. The firebrand public speaker turns out to be a typical teenage girl who quarrels with her brothers, likes watching The Minions, and swoons over pictures of tennis star Roger Federer.

Her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, a teacher and dedicated activist spreading awareness about the right to education, is the “He” in the film’s title, and a particularly interesting revelation is the exact extent to which he has influenced his daughter.

And while it is enlightening to look past Malala’s speeches at the United Nations and visits to refugee camps shown on television, one can’t help wondering if Guggenheim couldn’t have dug a little deeper, given such open access. Guggenheim has undoubtedly crafted a valuable and informative film, but his desire to tread softly around his revered subject leaves us with a sense of dissatisfaction. This is apparent in a section showing “men on the street” in Pakistan decrying Malala as a western stooge. The scene is quickly skimmed over, when it could have been another perspective to explore.

In the end, He Named Me Malala tells an important and engaging story. Given the pedigree of the director and the relevant-as-ever subject matter, it was no surprise to see it make the Oscar documentary longlist.

cnewbould@thenational.ae