Director: David Fincher

Starring: Ben Affleck, Rosamund Pike, Tyler Perry, Neil Patrick Harris

Four stars

The predominant image throughout David Fincher's work, from the uncovered horrors of the film Se7en to the Machiavellian manoeuvrings of the TV drama House of Cards, has been a torch beam cutting through the dark.

In his latest, the Gillian Flynn adaptation Gone Girl, he shines it into the deepest depths of neither a serial killer's mind nor a schizophrenic's madness, but on a far more terrifying psychological minefield: marriage.

In Gone Girl, Fincher has crafted a portrait of a couple rivalled in toxicity only by Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and one with just as much — if somewhat more subtle — role-playing. The results are a mixed bag of matrimonial mayhem, but an engrossing, wonderfully wicked one.

Despite its shifting perspectives, Gone Girl might be too male in its viewpoint. And the schematic set-up of Flynn's screenplay does sap some of its force. But Gone Girl is a delicious suburban noir.

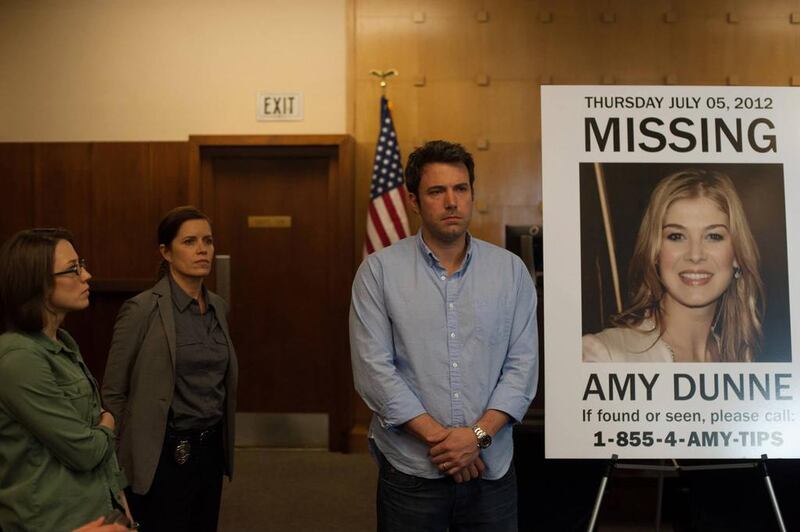

It begins with Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) caressing the head of his wife, Amy (Rosamund Pike), and wondering to himself: “What are you thinking?” It’s the film’s unsolvable mystery: the impossibility of knowing another, even someone who shares your bed.

On a regular morning in North Carthage, Missouri, albeit one kicked off with an early drink at Nick’s bar with his bartender twin sister, Margo (an excellent Carrie Coon portraying the movie’s voice of reason), Nick returns home to find Amy missing and scenes of a struggle. Even as she cheerfully pledges to help, detective Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) sticks notes around the house, marking areas of suspicion.

As the investigation turns its attention towards Nick and the glare of the TV media finds his concern for his wife unconvincing, we get an autopsy of the couple’s marriage.

In flashbacks narrated by Amy’s journal, she recalls their fairy-tale beginnings and — despite earnest intentions to avoid becoming “that couple” — their gradual dissolution.

This is the mischievous game of the movie, which hopes to sway your sympathies with each twist in the story.

The manipulation of image, both in public opinion and in private relationships, shapes the story, with Tyler Perry (in a spectacular performance) swooping in as the narrative-controlling lawyer Tanner Bolt.

Pike, in the fullest performance of her career, struggles to make Amy more than an opaque femme fatale. But — and it’s a big but — she does lead the film to its staggering climax, a blood-curdling sex scene: the movie’s pièce de résistance, the consummation of its noir nuptials.

Fincher’s sinister slickness and dimly lit precision has sometimes been considered a double-edged sword, a complaint that strikes me as missing the point. Mastery isn’t a negative.

Gone Girl doesn't give the director the material that The Social Network did. But you can feel him — aided by the shadowy cinematography of Jeff Cronenweth and the creepy score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross — moving closer to the disturbed intimacies of Roman Polanski.