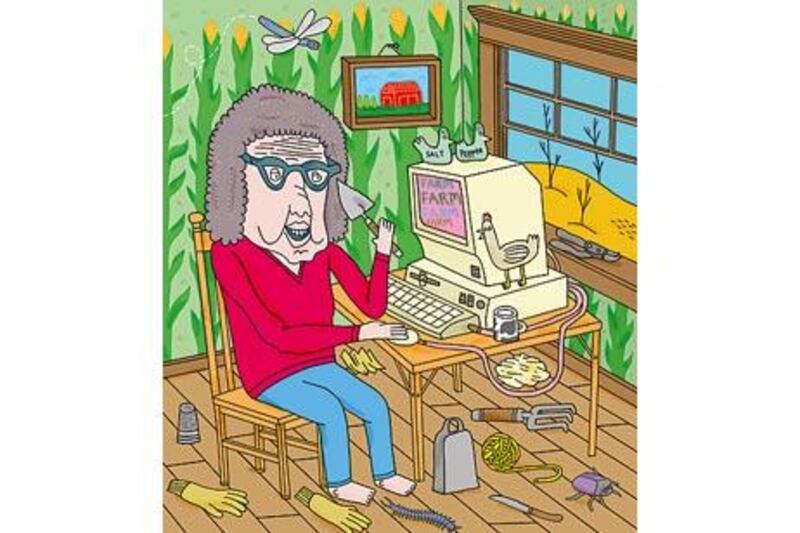

With 74 million players rushing online to tend virtual crops or herds of cattle, the makers of FarmVille have reaped millions from their free, pastoral and often addictive internet game. Jerry Langton explains the craze that some are calling the future of gaming. Jobi Thottungal and Hassan Waseem Dhami are typical of the guys you'll meet in the UAE. They're young and ambitious. They're both professionals - Thottungal in IT in Dubai and Dhami in sales in Abu Dhabi - and they're both farmers. Yes, farmers. They grow strawberries, broccoli and even raise cattle. They tend their crops every day and sometimes find themselves worrying about them when they can't get back in time - especially when a harvest is due.

But unlike those guys who grow melons and dates in Ras al Khaimah, their farms didn't cost them anything, they do not interfere with their social or professional lives, and they only take up the space of a laptop. That's because their farms are virtual. They - like 74 million other people around the globe - play FarmVille. It's an online game that can only be accessed through Facebook, and its phenomenal success has spawned dozens of competitors and has earned its maker - San Francisco-based Zynga - hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues.

It's a devilishly simple concept. The player signs up for free and receives six plots of virtual land. Two of them have strawberry and eggplant crops ready to be harvested, and the other four are ready for whatever the player would like to plant. Players can earn "farm coins" for selling harvested crops or "farm cash" for moving up an experience level. Both of those forms of virtual currency can be exchanged for seeds, trees, animals, buildings, vehicles and other items that make the player's farm more productive or attractive. Get enough currency, and you can even buy more land. And here comes the genius behind the game's incredible success: the easiest way to get ahead is to invite your friends to play.

Mark Skaggs, a vice-president at Zynga, says the company had low expectations when it introduced the game last June "just for a quick weekend friends-and-family test, with the expectation that after a few weeks, we'd roll it out to a general audience." They would have been pleasantly surprised if, after 24 hours, they had 2,500 players, but within that time, they had 25,000. Three days later, they had a million.

The huge size of the community, of course, encourages players to compete, and many of them become desperate to have a farm better than those of their friends. Some can get ridiculously elaborate. Friends can buy each other gifts - you'll need to get your credit card out for them, though - and consequently, they are highly prized among the serious FarmVille community. Of course, those players without the patience to build their farms the old-fashioned way can buy farm coins and farm cash. But many players, like Thottungal and Dhami, find that sort of behaviour to be a bit underhand. Neither has paid a dirham for their time on FarmVille, and neither expects they ever will. That's OK with Zynga, because they're making loads of money anyway.

Further amping up the addictiveness quotient is the fact that your farm needs you. Crops can go bad; unmilked cows can get sick. Players can get desperate about it, rushing home from meetings to make sure everything's OK at the farm. "At times it's almost psychotic because you think, I have to get home and milk the cows or they'll explode," says Robert Prowse, a Canadian television producer. Dhami is in the same boat. He always knows when it's harvest time and makes a point to rush back to his farm. "When the time comes for harvesting, I always play this game first, not any other game," he says.

Skaggs thinks FarmVille is a great success because people instinctively want to farm. "I think there's something fundamentally human about planting and growing, especially food," he says. "Maybe it's in our DNA and social consciousness, for some reason. It just feels good." I couldn't disagree more. Nobody today wants to be a real farmer - it is hard, dirty work, after all, and not always that lucrative. Still, more than 12 times the population of the UAE (or 14 times if you count the 15.1 million active users of the virtually identical FarmTown) is pretending to be one on their computers.

People have called FarmVille the future of gaming. It could well be. It's free, it's addictive, it's non-violent and it has a wide appeal. "A friend of mine, his 80-year-old parents play FarmVille," says Bill Mooney, another Zynga vice-president. "And I guarantee there aren't many 80-year-olds out there playing Halo 3."