We enter to a mystery. On a screen, slow-motion footage of people gazing off at something just outside the frame. An older man with glasses and a salt-and-pepper goatee stands still, watchful. A Sikh man with a turban and an American flag pin looks on, and a woman with a face mask over her mouth and sunglasses clipped to her blue shirt shakes her head.

These are, we soon realise, American faces – faces of all colours, all races, all genders, gathered together to peer at a spectacle both edifying and terrible. Then music, lurking just under our mental awareness, floats up in the mix, and we hear The Star-Spangled Banner slowed, ghostly, spectral.

A quick glimpse at the pamphlet for filmmaker Laura Poitras’s new show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Astro Noise, informs us that the gazers are standing near the pulverised remains of the World Trade Center in the weeks after two airplanes were flown into the buildings by terrorists. We read into every face we see, intent on crafting their inscrutable visages into a message, a perspective.

Is the man in the baseball cap with his camera in his hand shaking his head at the horror of what he is photographing, or is he momentarily distressed by a bad snapshot? Is the middle-aged man whose lips are tightly pressed together in a manner immediately reminiscent of then-president George W Bush wiping his eyes in sorrow, or in patriotic rage? Is the Sikh man’s flag pin a tragically necessary inoculation against home-grown bigots intent on seeking revenge on those they believe to be Muslim?

Poitras, an acclaimed documentary filmmaker who is making her museum debut with the Whitney show, provides us with no answers with O’Say Can You See, only more questions. For as we watch this loop, pressed against the walls of the darkened gallery, we can see a crowd assembling on the other side of the room, gathered to watch a video on the verso side of our screen.

The setting makes us instantly curious, our paranoia kicking in as we wonder what the others might be watching. Eventually, we drift to the other side, and are faced with grainier footage from a grainier time and place. Flashlights frame the outline of a body and a face.

We must pass by the watchers of the fallen towers to see the interrogations. More crucially, the two screens are conjoined, impossible to be glimpsed simultaneously. We can only ever take in one view at a time, even as the sound of the ghostly national anthem drifts onto our brief, fragmentary vision of other places.

“November 2001, Afghanistan,” the words on the screen tell us, and we come to understand that these two scenes, happening in opposite quadrants of the world, are taking place at one and the same time.

They are two halves of a single whole. We must venture beyond the inward-gazing patriotic view to see the damage being done in its name. And those keeping an eye on the Twin Towers are actually facing the wrong way, their backs turned to the criminal behaviour of their compatriots. They cannot see it, and perhaps, Poitras seems to be saying, they are intent on not being able to.

Astro Noise asks us to proceed through darkened corridors and switchbacks, never allowing us a glimpse of the lay of the land, or to anticipate what surprises might lurk for us around the next corner.

Poitras has created a physical space intended to replicate the ideological and intellectual space of permanent warfare, of the national security state run amok.

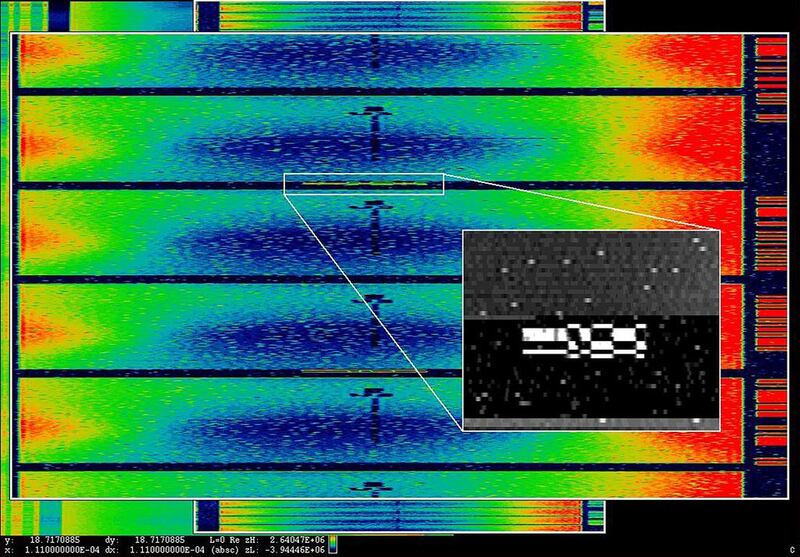

The strangely soothing Bed Down Location asks viewers to lie down on an oversized ottoman and gaze up at the gallery ceiling, where we can watch the night-time sky slowly scroll by overhead. The effect is strangely soothing – when do New Yorkers ever get to see the stars? – and yet the recorded chatter playing in the background is unsettling, as if the quiet over Yemen and Pakistan might be shattered at any moment by a murderous drone.

Disposition Matrix is a series of letterbox-sized cutouts in a darkened room, each with a photograph or document or short film hidden inside its mouth. Viewers must crane and bend to see each secret compartment.

The blips of information are delivered without context or initial explanation. Why are we looking at suburban golfers playing a round? What is this video of celebrants at a Yemeni wedding? Some of the items on display here are deceptively banal, while others, like the crude drawings of torture implements, are immediately jolting. As we learn when we arrive at the tail end of Disposition Matrix, almost all of the documents and films on display here come courtesy of Edward Snowden, the NSA (National Security Agency) whistleblower who was the subject of Poitras's last film, Citizenfour. Poitras is making art out of the found materials of current events.

It is not until the very last installation, November 20, 2004, that we are provided with any insight into Poitras’s motivations, or her own history. We hear her voice as she tells us that she had been “the target of a classified national security investigation conducted by the FBI and undisclosed intelligence agencies”, after witnesses saw her filming a surprise attack on American soldiers.

“The government never asked to see what I filmed that day,” she informs us in a never-ending loop. “This footage is unedited.”

The eight minutes and 16 seconds consist of Poitras looking down on an Iraqi family that is itself looking out from a rooftop on a chaotic scene below, with American tanks circling, and unseen Iraqi fighters lurking. The gallery’s video screen is surrounded by heavily-redacted American government documents pertaining to Poitras, arguing that the filmmaker “may have been involved with anti-coalition forces”, and another with a checked box for “DISSEMINATION OF INTELLIGENCE TO FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS”. The result is quietly chilling. A government that could be so wrong about Poitras, we understand, could be wrong about anything.

The entirety of Astro Noise takes place through the looking glass, penetrating the thin scrim of post-9/11 patriotism and paranoia, and digging through the archives of American national security excess. Poitras’s voice is vivid and compelling, and the documents are a reminder, if any was needed, that she knows this world as intimately as any other chronicler. She has made a surprisingly smooth transition from screening room to gallery.

But there remains something troubling about Poitras's hybrid role. With Astro Noise, as with Citizenfour, Poitras is blurring the distinctions between artist and activist and documentarian. What does it mean to go from making a documentary about Snowden to displaying his documents in an art museum? Does aestheticising the global war on terror neutralise the critique on offer?

Poitras is not just a chronicler of the ongoing national security state, but a victim, and her critique is coloured, as it rightly should be, by her own experiences. Where Citizenfour had been troubling for shielding its subject from reasonable criticism, Astro Noise is similarly disconcerting in its desire to render the very source material of an empire in ideological disarray as an aesthetic experience.

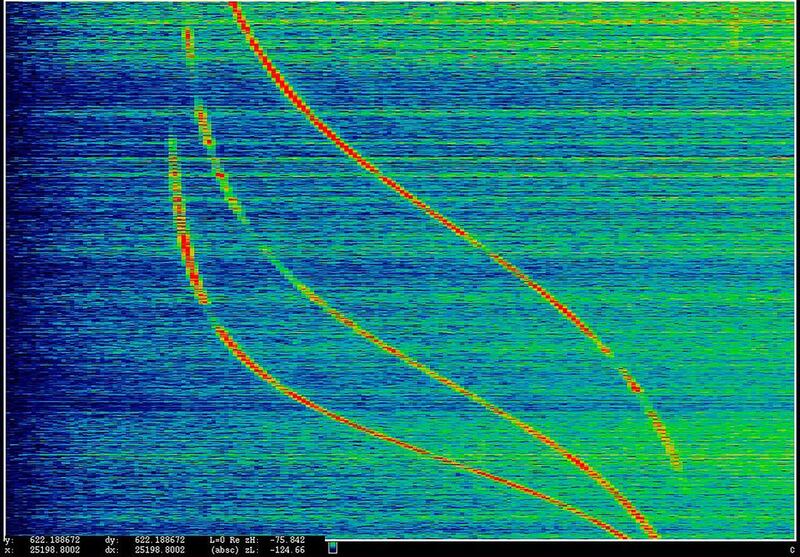

Can Poitras transform drone flight patterns into Barnett Newman zips without fatally compromising her advocacy, or advocate while in search of an artistic truth? On our way out the door, a computer running a programme called Wi-Fi Sniffer tracks viewers’ mobile use as they pass through the galleries. Like it or not, Poitras is reminding us, we are all being watched now.

• Laura Poitras: Astro Noise is open until May 1 at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Saul Austerlitz is a regular contributor to The Review.