Jeffrey Sipe previews the biennale's film programme, which includes a uniquely engaging offering from Iran's leading director, Abbas Kiarostami, in which the audience and their emotions take centre stage. Unlike the films shown at the local cinema, which are dependent on box office success, those screened at the Sharjah Biennial are part of a larger programme dedicated to examining artistic processes, re-imagining old narratives and looking at the role of the audience. The films, as well as other performances, have been selected by the section's curator, Tarek Abou el Fetouh under the title Past of the Coming Days.

"I am not putting together a film festival," says el Fetouh. "I was asked to put together a programme of film, performance and talks that are interconnected. "You will see in the films that many utilise other works, other forms. It is important, I think, to take works that have been made in the past and incorporate them into new works. I am very interested in looking at how art is made. I like art that investigates the creation of other art forms."

From a piece by renowned director Abbas Kiarostami to a documentary about an eccentric Tunisian filmmaker, the result is a collection of works that re-examines and, hopefully, renews the foundation of various art forms. It may be an intellectual undertaking - art, after all, has no obligation to entertain - but the result can be both challenging and tremendously engaging.

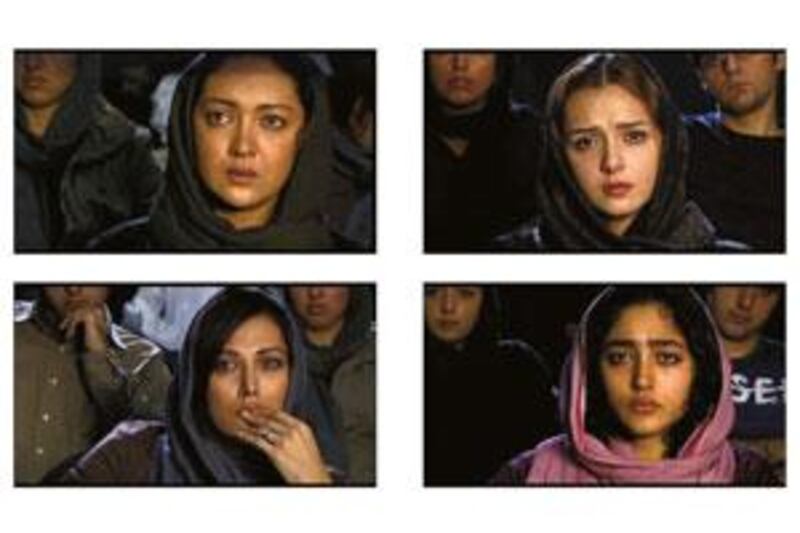

Winner of the Cannes Palm d'Or for Taste Of Cherry in 1997 and president of the jury in 2005, Abbas Kiarostami is by far the best known and most influential filmmaker to come out of Iran. Jean-Luc Godard has said that "film begins with DW Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami", and Martin Scorsese has said of him, "Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema". In Shirin, Kiarostami turns the tables - or more specifically the camera - by filming an audience of 115 women (one of whom is the Oscar-winning French actress Juliette Binoche) watching a stage performance of the 12th-century Iranian legend Khosrow And Shirin, the story of a woman loved by two men.

You never see the play and are privy only to the dialogue and sound effects. Instead, the women and their faces become the story that you follow. Whether you understand the Persian dialogue coming from the stage or read the subtitles, the result is the same. Eventually, the play's story fades as you realise that as a viewer in a darkened room staring at the screen, you are reflecting the actresses' faces. It seems obvious but the revelation comes with some force. It is no less forceful when you find yourself with the same expression as one of the women on screen - your hand on you chin or smoothing your hair, or a finger gently rubbing an eye. Many may identify with the woman whose eyelids slowly begin to droop until they close for just a second before she opens them and refocuses her attention. You have basically two choices while watching Shirin: fall asleep or sink deeply into thought about the symbolism of the images. It may not sound too exciting, but it is a fascinating depiction of the nature of narrative art. One hundred and fourteen of the actresses are professionals from Iran and the 115th is Binoche, whose recent dance performance in Abu Dhabi is further proof of her desire to explore how the arts interconnect. Beyond Binoche, though, as you watch actresses watching actresses, both under the guidance of an unseen director, relationships blossom. Your will find yourself not simply watching a film but being an element of a work of art. In one sense, you become the work.

In much of the Arab world there is lament over the lack of local filmmaking, which is blamed primarily on the lack of funding. Countering this is Moncef Kahloucha, a Tunisian force of nature who has embraced the do-it-yourself ethos by making homemade videos on VHS. He produces, he writes, he directs, he acts, he hires actors, he scouts locations, he films, he edits, he exhibits and he finally distributes the films himself.

VHS Kahloucha is about the one-man filmmaking machine. It's directed by Néjib Belkadhi who follows Kahloucha (a house painter when he is not making films) as he shoots, edits and exhibits his most recent work, Tarzan Of The Arabs. Kahloucha plays the wild-haired, loincloth-wearing hero who somehow has made a tourist village in Tunisia his home.

Countering this is Moncef Kahloucha, a Tunisian force of nature who has embraced the do-it-yourself ethos by making homemade videos on VHS. He produces, he writes, he directs, he acts, he hires actors, he scouts locations, he films, he edits, he exhibits and he finally distributes the films himself. VHS Kahloucha is about the one-man filmmaking machine. It's directed by Néjib Belkadhi who follows Kahloucha (a house painter when he is not making films) as he shoots, edits and exhibits his most recent work, Tarzan Of The Arabs. Kahloucha plays the wild-haired, loincloth-wearing hero who somehow has made a tourist village in Tunisia his home.

Shot on VHS, Kahloucha's films are hilarious and the production process bears traces of Hollywood. The films' stars become famous in and around the village where they live and work, while there is a young woman hoping for starlet status. Kahloucha and his sort-of producer get into creative arguments. And a bitter dispute erupts between a woman who wants to accept a role in Tarzan Of The Arabs and her husband, who forbids it. Against his wishes, she acts in the film and once it is finished, becomes infuriated when she spies her husband driving around town, loudspeaker in hand, drumming up business for the screening in a local coffee shop. Before he begins, of course, Kahloucha instructs him how he should do it. VHS Kahloucha is a straightforward documentary, but it also reflects the role films play in society everywhere. Shown to a group of expats in Italy, Tarzan Of The Arabs prompts both laughs and the warmth of recognition of filming locations. It is the screening in the village that is most eye-opening, however. Despite all the crudeness of the production, the audience watches wide-eyed, mouths agape and joyfully immersed. VHS Kahloucha is tremendously entertaining but challenging, too. If there is one film at the Sharjah Biennial that you absolutely must not miss, this is it.

Composed of scenes from Egyptian films made since the ascendancy of Hosni Mubarak to the presidency in 1981, The New Film is set almost entirely in police stations with Mubarak's portrait hanging in the background. The repeated use of images, which has become a feature of Egyptian cinematic vernacular, is likely to hit home with Arab viewers for whom Egyptian films have become a staple on television and in cinemas. At times funny, the repetition of near-identical scenes, dialogue and performances from decades' worth of film drives home the nature of commercial cinema. The omnipresence of Mubarak's image makes clear that there is a political message ingrained even in the most innocuous of films. Also showing is Yassin's Tonight, in which an Egyptian soap opera pushes the boundaries of television and ensnares viewers.

Like Yassin, Maha Massoun has carried out a mammoth research effort through archives of Egyptian film, assembling a collection of scenes that take place on or near the pyramids of Giza. There are love scenes, arguments, declarations of brotherly love - you name it. The film uses the images of the pyramids, surrounded by desert landscape that are familiar from big-budget Hollywood movies. No-one ever turns the camera in the other direction to show the developed community of Giza that fronts the monuments or the huge, sprawling Cairo just beyond. As implied in the title, by embracing the fairy-tale images of their country, Egyptians have created their own visual lexicon, making them tourists of their own identity.

Far and away the most difficult of the films to screen, Castellucci's is intent on delving deep into the archetypes of theatre. This work was performed in Marseille as part of a 12-city tour that saw him presenting different performances tailored to each city. There is nothing apparently narrative or representational in this other than the pure beauty of the images, a jarring mix of colours on a theatre stage. It will be worth attending Castellucci's talk, however, to hear what the film, and the abstract images, are all about.

One of the most traditional films in the programme, Sherif el Azma's examination of two very different singers - Moustafa Amar, a polished, produced pop idol and Dunia, a sort of working-class hero - evokes the manner in which popular culture reflects social realities in Egypt. Amar appears in well-lit, over-the-top music "videos" surrounded by bikini-clad women lacking any hint of reality, while Dunia, filmed in dim light, leads the same life of the taxi drivers and labourers who sing his praises.

Part of an ongoing series of reflections on a group of men in Beirut who swim in the sea every day, no matter what the weather. Al Sohl dubs her voice over those of the gruff men. Her reflection goes beyond the video to photographs, writings and lectures in an ongoing project with no apparent end.

In 2007, the Institute for Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London invited 26 artists to submit proposals for an Iraq war memorial. "The intention is not to find a definitive memorial to a war - a difficult task at any time, and especially in the context of an ongoing conflict," the ICA said about the project. "Instead, the exhibition explores different views of the Iraq war, and different perspectives on what can or should be memorialised." Iman Issa's film was one of the submissions." Created using found images and footage, the film focuses on one person's account of the war and the landscape of Iraq.

For show times and venues, visit www.sharjahbiennial.org