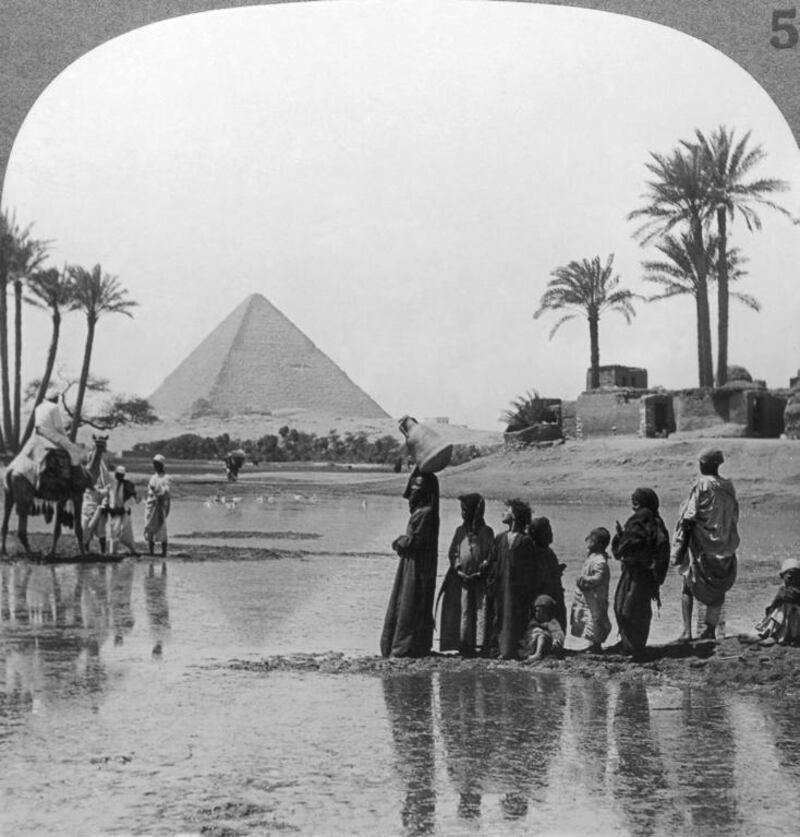

Egypt, Herodotus wrote, “is an acquired country – the gift of the river”. Toby Wilkinson, the Cambridge Egyptologist, goes the ancient Greek historian one better. “Without the Nile,” he writes in his spirited historical travelogue, The Nile: Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present, “there would be no Egypt.” In a country that is 95 per cent barren desert, the great river has been a literal life spring of peoples and cultures: “It has shaped Egypt’s geography, controlled its economy, moulded its civilisation, and determined its destiny.”

The river has seen the rise and fall of empires, religions, kings and pharaohs. Greeks, Romans; Christians, Jews, Muslims: all have left their mark on the river, and have, in turn, been influenced by its flowing currents and annual floods, which nourished crops and enriched the soil. Traders sailed up and down the river hauling goods for exchange. The felucca, the distinctive vessel with a curved mast and a single triangular white sail, is still a sight on the river today, “a stalwart of Nile travel”.

Though he is prone to florid declarations – the grandeur of the desert landscapes meeting the water, the brilliant sunsets and ancient monuments, hold Wilkinson rightly in awe – the author is an ideal guide to the terrain. From its headwaters, the Nile flows from south to north, where it empties into the Mediterranean. Wilkinson starts his journey in Aswan, site of the famous High Dam and the crashing waters of the First Cataract, making his way northwards via obvious sites – Luxor and western Thebes – and sundry other spots that might not be familiar to the general reader. One of the strengths of the books is how Wilkinson goes well beyond the usual tourist’s itinerary, highlighting lesser-known rulers and out-of-the-way destinations.

One such place is Nagada, “a poor, undistinguished community of dusty streets, grubby children, hard-pressed adults, scratching chickens and semi-feral dogs”. Present day Nagada may be a backwater, but it was at an ancient burial site here, excavated in the late 19th century, that the very beginnings of pharaonic civilisation can be traced. “Unbelievable as it seems today,” Wilkinson observes, “for several heady centuries in the early and middle parts of the fourth millennium BC, Nagada was one of the two or … three most important places in the whole of Egypt.”

Wilkinson, the author of the much-praised The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, keeps his eye firmly on the past. He is an expert on antiquities and the Egypt of the pharaohs. At times, The Nile is less about the Nile than about the country’s ancient past. (Then, it is this past that generates huge revenue for the Egyptian economy.) Wilkinson sniffs a little at the tourism trade at Luxor, but he still writes well about the glories of Karnak – “the greatest religious complex in the world” – as well as the haunting Valley of the Kings, where some of ancient Egypt’s greatest rulers, among them Amenhotep III, are buried.

Wilkinson is strong on the accretion of cultures that have grown up alongside the Nile; he is deeply attentive to the rich cultural mixings and minglings that have defined the civilisations of the Nile over several millennia. He is keen on the pluralism of Egypt’s past. In Aswan, he notes “how every period of history has left its traces. The attentive visitor can observe a palimpsest, with remains from pharaonic, Ptolemaic, Roman, Christian, Islamic, colonial and post-colonial times to be found side by side or one upon each other.” Here, in the Cataract region, Egyptian and Nubian peoples intermingled, “across a permeable frontier as far as people were concerned”.

Aswan is the site of two epic projects to harness the Nile and control its annual flood. The first, completed in 1902, was guided by British engineers and capital. It helped propel Egypt into the modern world, giving it the ability to irrigate valuable export crops such as cotton. Then, later in the century, president Gamal Abdel Nasser spearheaded the building of the famous High Dam. This massive endeavour meant the end of the annual inundation, but it also meant the containing of the rich sediments that made the soil of the Nile flood plain so fertile. Lake Nasser, Wilkinson notes, changed the climate in southern Egypt, bringing more rain, which has meant more mosquitos, and thus more malaria.

Wilkinson’s tour of the Nile is punctuated with frequent accounts and reflections of Egypt’s famed ruins, which can be found up and down the river. Farther upstream from Aswan, the Luxor Temple, the core of which was built during the reign of Amenhotep III around 1395BC, has been a site of devotion and worship for several religions. “Nowhere else on Earth,” Wilkinson writes, “not even the temple at Jerusalem – has seen such a continuity of worship, stretching back 3,500 years.”

The temple began as a “holiday home”, in Wilkinson’s words, for the Theban god Amun. Later, Alexander the Great was so taken with the indigenous rites he commissioned a granite shrine festooned with scenes showing him in phaoronic garb. The Roman emperor Hadrian also built a shrine devoted to the Greek-Egyptian deity Serapis. Such fusions and cross-cultural exchanges have defined ancient Egyptian religion. It influenced the iconography of early Christianity, Wilkinson notes – “the iconography of the Virgin and the child copied the imagery of Isis and Horus, while the key tenets of the Trinity, Resurrection and Last Judgement showed extensive borrowings from Egyptian ideas”. The Arab conquest of Egypt, from 639-641AD, brought Islam to Egypt, and the Luxor Temple found a role in Muslim culture that spread through the country. “If civilisation can be encapsulated in its monuments,” the author writes, “Luxor Temple represents the history of Egypt in microcosm.”

Wilkinson is also acutely sensitive about the Europeans – men and women – who came before him to study Egypt’s ruins and investigate its past. He is inspired by the journeys of Amelia Edwards, whose 1877 book, A Thousand Miles up the Nile, remains a classic. She was a pioneering Egyptologist, who strove to protect the country’s monuments from destruction. He also details the exploits of William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the excavator of Nagada and “the father of Egyptian archaeology”. Flinders Petrie was instrumental in putting his field on the proper scientific footing, and “excavated at more sites in the Nile Valley than any other archaeologist”.

But Wilkinson notes that discovery and digging was often bound up by the dictates of imperialism. After Napoleon’s venture into the Nile Valley, Europe’s powers competed for the spoils of Egypt’s ancient past. The British Museum benefited from the exploits of Giovanni Belzoni, who hauled off the statue of the Younger Memnon from the temple of Ramesseum. And the giant obelisk that used to grace the entrance of Luxor Temple today can be found at Paris’s Place de la Concorde. The European encounter with Egypt was mixed. For all those who came to preserve Egypt’s heritage, others came to take it away.

Wilkinson’s tour is rich and leisurely, filled with digressions galore. He enjoys the slow progression towards Cairo. His vision extends beyond the Nile into the vast, inhospitable reaches of the Eastern Desert, which has been touched by the river in mysterious ways. Here, “all in the middle of the desert with not a drop of water in sight”, are numerous scenes, dating back to the fourth millennium BC, painted on rocks, cliff faces and other surfaces, of boats of many shapes and sizes being hauled or propelled by crews of rowers. The meaning of such rock-art images are uncertain – are the boats for festivals or funeral ceremonies? No one is quite certain of their purpose, only that the Nile’s reach and influence is pervasive even in the barren desert.

Wilkinson’s journey ends, appropriately enough, in the great capital of Cairo, the largest city in the Arab world. He touches on Egypt’s political future and the events in Tahrir Square. Uncertainty reigns, but he casts his gaze to “the eternal friend upon which every generation of Egyptians can depend, the Nile”.

Matthew Price’s writing has been published in Bookforum, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe and the Financial Times.