A packed house attended the RichMix cinema in Hackney, London, to watch the Egypt in Focus event presented by Land in Focus on April 7 - an evening of discussion, debate, music and film, including eight short films, seven of them UK premieres. That the organisers had to arrange for more seats was a sign of how the recent events in North Africa have captured the imagination.

Land in Focus is a not-for-profit organisation that aims to showcase the films and culture of Africa, Latin America, Asia and Eastern Europe. The emphasis is on regions of the world that the organisation believes have been neglected by the usual exhibition channels in the UK.

The focus on Egypt became pressing when Alex Hands, the artistic director of Land in Focus, found himself in Cairo during the recent uprising and subsequent removal of the government.

Usually, the events offer a free platform for young directors to have their work theatrically exhibited to an audience that may otherwise be unaware of their work.

The interest in Egypt meant that this year the organisation hosted a talk on Egyptian cinema and the short films being shown, led by Dr Marie Hammond, lecturer in Arabic popular literature and culture courses at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

In focus were the eight short films being shown that night. With the exception of the 1975 work, The Sandwich, by director Atteyyat el Abnoudy, all of the shorts were made in the past four years and were receiving their UK premiere. The Sandwich was also the only film that was made outside of Cairo, highlighting how the metropolis has come to define the Egyptian art scene and cultural life.

Hammond admitted she did not usually specialise in short films, as she gave a potted history of Egyptian cinema that included reminders of some key dates in Egyptian history such as the revolution in 1952, the Six Day War in 1967, the release of Night of Counting Years (aka The Mummy) in 1968 and the appointment of the director Shadi Abd Al Salan as the director of The Experimental Film Unit in Cairo. This, she noted, preceded a creative period in the arts wherein there was a revolution in documentary stereotyping in which Egyptian documentary filmmakers stopped using voice-over narration and instead allowed the images to speak for themselves. Similar attitudes prevailed in America and France, with the direct cinema and cinéma verité movements. Hammond argues that the 12-minute-long The Sandwich was born from this experimentation and its depiction of the city of Al Abnoud.

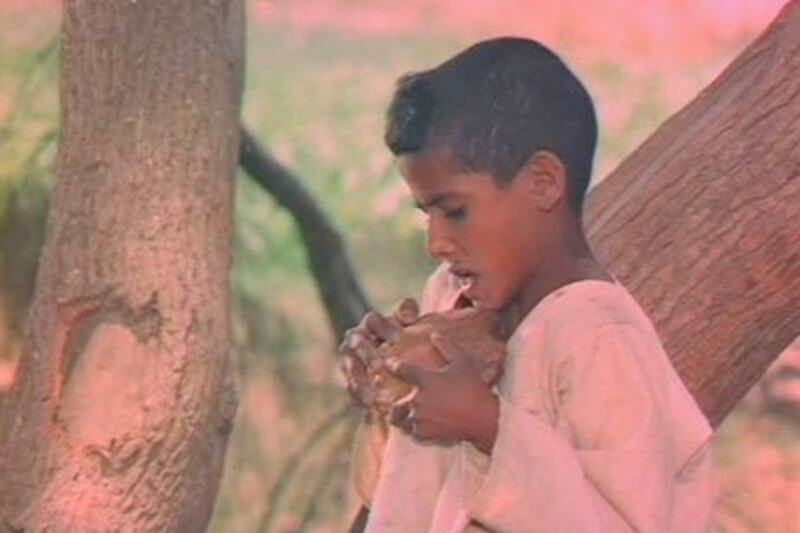

The Sandwich is a rather clever film about the battle between modernity and tradition - especially in a rural setting. It starts with an announcement that the village depicted is 600 kilometres south of Cairo on the way to Luxor, but the train does not stop there. Yet in the village it's clear through the process of bread-making and the goats running around that this is a life that is on its last legs and unsustainable. The centrepiece of the film is a compelling scene in which a young boy milks a goat in an attempt to ensure that the bread of the sandwich that he wants to eat is not dry.

Hammond pointed out that of the seven new films to show in the UK, most were easily decipherable except Mount of Forgetfulness, the 2010 film from visual artist Hala Elkoussy. The commentary was particularly helpful in deciphering the abstract production that had echoes of the work of Elia Suleiman, which took tales from Egypt's rich oral storytelling tradition and mixed musical interludes in a patchwork of scenes. Key events in the history of modern Egypt are alluded to in the film that is about the death of storytelling and features a character called Rawi, a name that means storyteller.

The quality of the films was extremely high, proving that in times of change, artists often respond with intriguing works. What's also interesting about short films is that because of the lower budget associated with the shorter format, the artists have been able to make films without the traditional structure and have responded with movies that question the position of Egyptians in present-day society.

The first film shown was Solo by Laila Samy, and like several of the works, it featured a female as a protagonist. It was a tale of frustration with life and tradition and the life on the street and is told in the moments before the protagonist takes her own life.

Setting Egypt in context with the rest of the world was Rise and Shine by Sherif Eben, which is an adaptation of a Dario Fo play about a desperate mother's search for her lost keys. The symbolism of the baby and keys and the lack of men all play into the sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Another intriguing work about the battle between modernity and tradition was Pale Red by Mohammed Hammad, about a girl trying to buy more modern underwear after her friends laugh at her old pair. Her new choice meets with the disapproval of her grandmother.

The nature of storytelling was a strong theme in all the films and is a feature of both Salam ya Salam by Abdelsalam Moussa and the excellent The Chair Carrier by Tarek Khali. Made months before the revolution, The Chair Carrier is based on the short story by Yusuf Idris and is about the refusal of the power elite to recognise the problems with tradition and refusal to accede power.

The final film of the evening, Clean Hands, Dirty Soap, is a 2008 film by Karim Fanous that had won several awards at festivals. It's about a bathroom attendant who falls in love with a belly dancer.

The evening ended with a music programme featuring singers, DJs and oud players to round off a night that seemed to indicate that Egyptian cinema may be on the road to critical acclaim once again.