A year ago, The National reported on the Barefoot College, a school in the Indian state of Rajasthan that invites illiterate grandmothers from rural parts of Afghanistan, South Sudan, Peru and elsewhere in the world to take a six-month course on solar engineering, with the intention that they will return home ready to create sustainable electricity systems and pass on their skills.

Now, two Egyptian-born filmmakers have made a documentary about Rafea, a Jordanian Bedouin woman who is chosen for college but is forced to struggle against the prejudices of her unemployed husband and deal with her own feelings about leaving her young children behind.

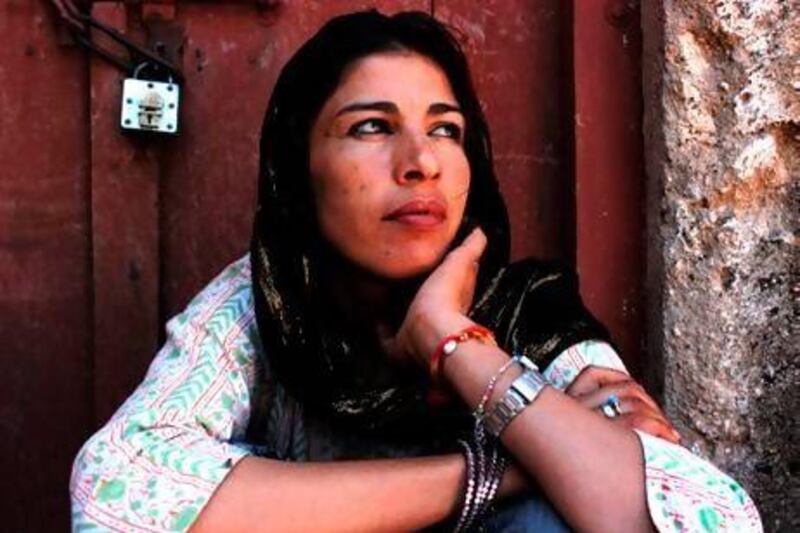

Rafea is funny, bright and resilient but she faces enormous obstacles as she tries not only to change the economy of her village but also to inspire the women around her to seize control of their lives.

Ahead of its UK premiere at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in London, Mona Eldaief, one of the -directors of Rafea: Solar Mama, talks about the highs and lows of capturing the story on film.

How has the film been received?

We just showed it in Jordan on International Women’s Day in an enormous theatre and it got a standing ovation. The audience was roaring and crying the whole time. It was amazing.

Why do people relate so strongly to Rafea?

She is such a magnetic, inspirational character; she just pulls herself up again and again. If she’d been born in a different situation, she would be running a country.

At what point did you know she would become the film’s focus?

Originally, we were going to follow three women from three different continents, but [Rafea’s] drama happened on the spot while we were filming.

When she returned to Jordan – after her husband said: Come back or I’ll divorce you and steal the kids while she was giving her mother a lecture and saying: We can’t just sit around and smoke cigarettes, there are 300 people unemployed [in the village] – at that point I called the producer and said: We have the story right here. This woman is incredible. She’s going to get herself out of this situation.

Were you torn between wanting to get involved and staying impartial?

Oh, I got involved. When I went back to New York, Rafea’s husband would call me and complain about his wife and I tried to knock some sense into his head.

Of course, that didn’t make a bit of difference. We’d keep telling Rafea that she is a brave woman and just praise her constantly.

Did that relationship help when it came to capturing the film’s most intimate moments?

When I was in her village, the camera became like a witness: Can you believe this is happening? This is the situation I’m in.

Yesterday [Rafea] was on stage at a community screening and a very conservative woman said: How can you expose your husband like this? Aren’t you ashamed?

Rafea answered: There’s nothing shameful about the truth. And that’s what the camera did – it documented the truth. This film is for everybody out there in a similar situation, to see that they’re not alone.

Is Rafea’s story relevant to life outside these rural communities?

The domestic male-female relationship is similar all over the world, [as is] the want to make something of yourself and provide for your children, but at the same time being torn between this and caring for your young kids. That has struck a universal chord, for sure.

What were the most rewarding moments while you were shooting?

Rafea’s humour stands out, and the woman in the Barefoot College bonding with her without language. They keep in contact by phone in broken English: I love you, I miss you. They come from different cultures but they all come from poverty and repression; they had a shared experience of transformation.

What’s next for you?

We want to show the film in local communities throughout the Arab world and have an NGO on the spot locally that promotes women’s empowerment, so that people don’t just watch the film and think: Oh, she’s such an inspirational character and she got lucky, but our lives are doomed. If they want to sign up to build houses, weave rugs or start their own candle business – whatever the NGO is – they’ll have an opportunity after the film is shown.

• The Human Rights Watch Film Festival will be held at venues across London from today until March 22. The screening of Rafea: Solar Mama and Q&A with filmmakers will be on Friday and Saturday. Visit www.ff.hrw.org for more details