Rob Ryan is one of the UK's most sought-after artists, whose delicate, romantic paper cuts have earned him both commerical success and artistic acclaim. Lydia Slater meets the man leading the revival of an ancient art form and inspiring a new generation of cutters. I've never met the artist Rob Ryan, but I know exactly what he's going to look like. On my way to his workshop in the East End of London, I imagine an Adrien Brody type; slender, long-haired, poetic-looking. Such, after all, are the silhouettes that people his astonishingly delicate and romantic paper-cut artworks.

Amid landscapes of twining flowers or tossing trees, surrounded by birds and bells, shaggy-haired young couples swing, embracing, from branches, paddle hand-in-hand through water-lily ponds and cuddle in rowing boats. Such decorative sentimentality is undercut by the thought-provoking and often melancholy words that are cut into the images, creating irresistibly poignant art. A father plays in branches with his two children; etched among the twigs is his fearful prayer, "Please God don't let me have too much", emphasising the fragility of his happiness. In another image, a delicate nest of spring twigs contains a clutch of five eggs, each bearing a bitter reproach: "Where are you", "Waited and waited", "How could you do this to me"? What will hatch from those eggs? Vipers?

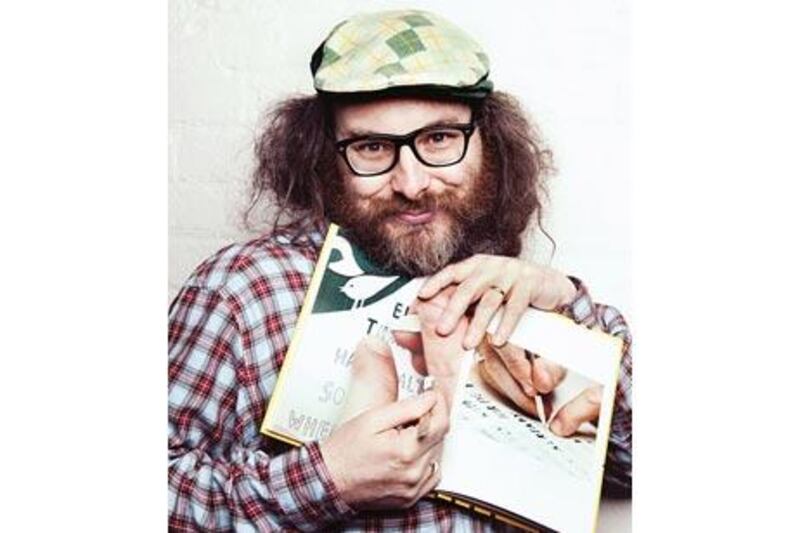

Anyway, when I climb carefully up the appropriately jigsaw-cut staircase to Ryan's studio, I'm quite taken aback to meet a burly, balding and bearded middle-aged chap in thick glasses, sporting a curly mullet. Five minutes in his company, however, are enough to reassure me that I am in the presence of a genuine, if alternative, romantic. "What I'm interested in is people, and how they connect with each other," he says. "Talking about love isn't sentimental, it's telling stories about how you feel and how you want people to like you."

We are sitting on a sofa with a denim patchwork cover, made from several pairs of Ryan's worn-out jeans by his wife of almost 30 years - "we've been together since I was 18 and I'm 47 now, so maybe that's a proof of my romantic nature," he says smiling. As we talk, two young women assistants are painstakingly using scalpels to trim stacks of greetings cards that have been laser-cut from his original template. The fruits of their labour will be sold in Ryan's East London gallery-cum-shop, Ryantown, a glorious little boutique selling everything from one-off artworks to china, cushions and even teddy bears, all bearing his unmistakable silhouettes and slogans. Dropping by in the interests of research, I was transfixed with desire for a simple roll of exquisitely detailed white-on-black sticky tape. Even the shop's paper carrier bags are covetable.

The immediately appealing nature of his work means Ryan is constantly in demand to collaborate with designers. He has produced a range of clothing and textiles with Paul Smith and jewellery with Tatty Devine; his designs adorn the glossy pages of Vogue and the windows of the London department store Liberty, as well as a limited-edition camera for Urban Outfitters, a product range for Japan's Sazaby company that includes scarves and bags, and cut-outs turned into appliqué for the US fashion design group Project Alabama. I realise I already own a Rob Ryan without knowing it - he was commissioned to laser-cut a wintry palace into the cover of Fortnum & Mason's Christmas catalogue and I found the tiny cut-out image so striking that sI kept it.

The commercial nature of Ryan's work doesn't prevent him being taken seriously as an artist. He's just had a major exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, for which he created 11 huge window decals. Now, he's working on an illustration for the poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy's forthcoming children's book The Gift, which he says is all about death - "very beautifully told and quite dark in places".

He opens a folder and takes out one of the paper cuts to show me. It's a delicate, astonishingly detailed depiction of a flower-covered meadow, through which a little boy is leading a herd of cows. Behind him, a medieval town can be glimpsed through a forest of pine trees. The work, fragile as lace, hangs swaying from his fingers. I long to touch it myself but I don't dare. Any thoughtless pressure and days of painstaking craftsmanship will be destroyed.

Paper cutting is an ancient form of art. The earliest existing paper cut is Chinese and dates from the sixth century, but the art is still popular there today, hung around the house as a bringer of good luck. Across the globe, there are different techniques and styles used in cutting paper. In India, for instance, the paper cut is often used as a stencil through which coloured paints are sprayed, a technique adapted by graffiti artists such as Banksy. Eighteenth-century Europe saw a rise in the popularity of silhouette art, cut from black cardboard and mounted on white paper. It was not only a cheap and comparatively easy form of portraiture, it also tended to be a more flattering form of depiction.

Hans Christian Andersen was a prolific paper cutter who left hundreds of examples of his whimsical and detailed work for posterity. He liked to cut as he told stories to children, ensuring their complete attention. His modern equivalent is Jan Pienkowski, whose fantastical, delicate silhouettes adorned the favourite fairy tales of my childhood. Latterly, the American artist Kara Walker has used the technique to create shocking and highly politicised images confronting thorny issues of race and gender.

Walker's art aside, this rich history was virtually unknown to Ryan when he started paper cutting seven years ago. "The appeal had something to do with its very simplicity. Instead of having a canvas and adding paint to it, you start with a piece of paper and take bits of it away, so you have to make it less to create your image." The other factor in its appeal is a mechanical one: for a paper cut to work, everything in it must connect physically, must interlink, from a bird flying through the sky to the tears falling from a face. "Doing a large expanse of sky is quite difficult," he says. "You have to invent bits and pieces to hold it together."

Is it too fanciful to speculate that a rootless upbringing has left him with a longing for this kind of universal connection? He was born in Cyprus to Irish parents. "My father was in the RAF for years and we travelled around the world constantly," he says. "It's not easy when you're a kid - you couldn't even start making friends. I went to six different primary schools and I was always the new kid. By the time I'd managed to make friends, I'd have to break away again. This is where we tread into heavier territory, but if you always move, you do feel isolated. I suppose I did begin to live inside my head a bit more than the average seven-year-old."

His two brothers are both significantly older than him, so he would spend hours drawing pictures alone. This solitary pastime led to his taking a BA in fine art at Nottingham Trent Polytechnic, followed by three years of printmaking at the Royal College of Art. When Ryan graduated in 1987, he began painting, but his pictures were always full of words. "In the end, they were becoming almost a whole page of words with no pictures at all. I wanted to go back to a purely visual medium." So to try to banish this attraction to text, he decided about eight years ago to start cutting images into folded paper, inspired by a book of Swiss paper cuts he owned. "If you included any words on them, they would be repeated back to front and it looked silly. I didn't put any words in for a year or so, but then they came back - I found loopholes." Instead of cutting from folded paper, he would cut an almost symmetrical image ("I do like symmetry, putting the world in order") but out of a single sheet, then carve phrases in the image with a scalpel rather than a brush. It is the words, he believes, that are his "X factor". "Maybe it's because there's a certain authenticity about them. They're not written from a sentimental point of view."

To his surprise, he found that the people responded more to this fragile, decorative art, than to a painting for which he had, as he put it, thrown his "guts on the gallery wall". He hasn't lost his own fascination for the technique. "That's the great thing about doing something you love. It keeps you company your whole life. My work is like my friend. I am quite nervous and paranoid," he adds, suddenly confessional. "I do this because this reassures me. It's the words, but also the process, because you do drop down to a certain pace." Ryan uses a special kind of paper - a large-format smooth, white stock usually used for Bibles - and draws and redraws the image on it carefully until he is satisfied, which is the lengthiest part of the process. The drawing is then cut out with a scalpel, starting with the tiniest details and ending with the biggest expanses, which can take up to three days of concentrated work. Once the cutting is completed, the paper is sprayed to the desired colour. "But we can be quite fast if we have to be. There have been times when we've wanted to do a big paper cut for the shop window and we've had five people working on it at once, fighting for elbow space, because we needed to have it done by the end of the day. It can be quite nice - you get rough edges and it looks a little bit different." Ryan is in the comfortable, comparatively rare, position for an artist of being able to make a decent living from his work alone. His screen prints sell for about US$400 (Dh1,500) on the craft website Etsy.com, and special commissions can run into thousands. Demand for his work consistently outstrips supply, which is partly why he's going into licensing a range of Rob Ryan products, including the ceramics which he is currently working on. The other reason he is doing it is to deter the copycats. "I feel bad saying this, but my work is very easy to copy, and I felt it could almost get to a point where I'd have to stamp my identity on it. People blatantly lift my work and put it on their websites as their own. The more people know my work, the harder it is for someone to copy." More positively, his creations have inspired a new generation of paper cutters. "When I first started there was only me and a couple of other people, and now it's sort of exploded," he says, shaking his shaggy head in wonderment. "I suppose these things come in waves but I went to give a talk at a college last week and there were about 40 people all doing paper cutting. I don't see myself as a paper-cutting artist. I'm an artist. Paper cutting is just a very simple way to express what I want to say." Examples of Rob Ryan's work can be seen at www.misterrob.co.uk, and bought and shipped worldwide from www.etsy.com