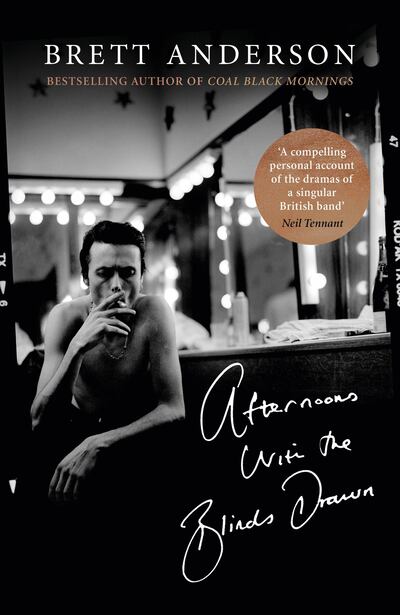

Brett Anderson begins Afternoons with the Blinds Drawn, his second volume of memoirs, with an admission. "So here I sit writing the book I said I wouldn't write, talking about the things I said I didn't want to talk about. I suppose it was inevitable." That nicely ironic punchline nods towards several things. The success of part one, Coal Black Mornings, which narrated his story from deprived childhood to the singer-songwriter and flamboyant spiritual centre of '90s Britpop pioneers Suede. His self-confessed habit of acting against his best interests. And, finally, a vow he made to the reader in that first volume: "The very last thing I wanted to write was the usual 'coke and gold discs' memoir with which we've all become so familiar."

If you need an example of what Anderson means here, you could do worse than read The Heroin Diaries by Motley Crue bassist Nikki Sixx. This hymn to heavy metal excess (biting members of AC/DC, years of addiction and more near-death experiences than a mayfly) can be summarised by the one-liner: "Anything worth doing, is worth overdoing."

Anderson, by contrast, wants to write rock-star autobiographies without the cliches, a tension that could describe his entire musical career. When Suede became stars in 1992, seemingly overnight, they did so by taking classic poses – David Bowie's androgynous theatrics, Sex Pistol John Lydon's alienation, Morrissey's mournful vulnerability, Lou Reed's sordid bohemianism – and disrupting them to their own mischievous ends: raucous tales of doomed romance and death, set in an enticingly squalid, cut-price Britain, all of which Anderson delivered in a stylised cockney whine.

What Anderson performed onstage, he has essentially realised on the page. "This is a book about failure," he wrote at the start of Coal Black Mornings, before excavating an isolated, cash-strapped upbringing, his formative salvation through art and music, his on-off love affair with London's demi-monde and his evolution into the most charismatic singer Britain had produced in years. Having scaled pop music's heights with swagger, Anderson's most predictable, and therefore tedious, stunt was to slide straight back down the same greasy pole into a miasma of drugs, drink and dreaded musical differences.

Could anyone relate this familiar story of break-ups, comebacks and comedowns without resorting to stereotypes? To Anderson's credit, his intelligence, wry humour and unflinching self-criticism all ensure that Afternoons with the Blinds Drawn largely succeeds. For example, when he explores how he confused his flamboyant onstage persona with his previously retiring off-stage personality: "I staggered between bizarre dalliances and sticky gaudy dramas, my private life becoming increasingly odd and rootless. For a while it felt like I was trapped inside a Futurist painting, restless and kinetic as I ricocheted around locked within a strange new dissonant version of reality."

This mixture of pretension and insight will be familiar to any Suede fan, and proposes Anderson as one of a new breed of rock memoirists – the alt-rock memoirist, perhaps – who fights the commonplace with both their prose and songwriting. Take the moment in Coal Black Mornings when Anderson mockingly recalls "self-important celebrities such as Cher and Peter Gabriel mincing around in their ridiculous costumes while we just smoked and laughed with the make-up girls at the utter naffness of it all".

The emergence of this new wave of autobiography owes something to timing: the guiding lights of punk, post-punk, indie, grunge and hip-hop are now at an age when time, ego and money tempt them to reflect.

This has resulted in a different sort of rock narrative – one less concerned with fame and fortune than disclosing the intimate stories that make people want to write songs in the first place. The goal is not to impress, shock or to sanctify, all of which might be aimed at the airbrushed Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody, but to enlighten, confide and confess.

The trend began (like so many others) with Bob Dylan. His Chronicles was a revelation precisely because Dylan refused to kiss and tell about the so-called headlines of his life, offering instead meandering yarns about his upbringing and early days in New York.

Similarly eye-opening was Tao of Wu by RZA of hip-hop collective Wu-Tang Clan. Alongside freestyling advice, one can read meditations on religion, mathematics, philosophy, chess and his beloved kung fu. "I'm always down to learn," as RZA notes modestly. Anderson's more obvious peers include his own heroes. Lydon gave full vent to his seemingly infinite contradictions and antagonisms in Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs: "Sometimes the absolute most positive thing you can be in a boring society is completely negative. It helps." Morrissey's Autobiography, which he demanded be published by Penguin Classics, strikes a note of eerily familiar anti-establishment grandiloquence. His memorial to Headmaster Mr Coleman – "Convincingly old, he is unable to praise, and his military servitude is the murdered child within" – all but renders The Smiths's Headmaster Ritual in prose.

It is hard to miss how many of alt-rock's finest autobiographers are women (Patti Smith, Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon), who inevitably shake up the form by shining startling lights into the darkest, least examined corners of their craft: sexism, violence and exploitation on the one hand, but also family, friendship and home. Slits guitarist Viv Albertine offers eloquent proof that punk's most radical voices existed beyond the movement's macho provocateurs in her book Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. By playfully highlighting the book's most scurrilous sections in her introduction, she frees readers to absorb her tales of emigration, abusive fathers, surviving cancer and excelling as a woman in a man's world. Love of music is never far from rage, as when she returns to Earth after hearing John Lennon sing You Can't Do That: "I look up and down the street as if someone might pop out of a doorway and whisk me away, but all I can see are houses, houses, houses, stretching off into infinity. I feel sick. I hate them."

If Kristin Hersh's Rat Girl, previously published as Paradoxical Undressing, reads with the unguarded intimacy of a diary, that's because to all intents and purposes it is one, recording how between 1985 and 1986 she moved to Boston with her band Throwing Muses, made a classic, if wonky debut album (also Throwing Muses), was diagnosed as bipolar and discovered she was pregnant. All when Hersh was just 19. Her impressionistic, aphoristic style sharply convinces why swimming is better than drugs: "Swimming sweetly reflects the human condition: we're never on solid ground. And there's a whole story down there, like a love life." The punchline follows a sentence or two later: "I've never found anything better than water for putting out fires."

Similarly bracing alt-memoirs will be released within weeks by Debbie Harry, Liz Phair, Wilco's Jeff Tweedy, Mark Lanegan and Flea, of Red Hot Chili Peppers. Equally intriguing, if more mainstream offerings include autobiographies by Elton John and Wham's other half, Andrew Ridgeley. If these considered, challenging and invigorating narratives are not your bag, there is always a new book by Francis Rossi of Status Quo, whose band name perhaps says it all.