In an ideal world, what kind of voice would you like your virtual assistant to have? Perhaps that of a furious police officer? A sarcastic taxi driver? No way. If we're going to enjoy our interactions with virtual assistants such as Apple's Siri, then we've got to be fond of them and a huge amount of research goes into bestowing them with attractive personalities. Siri was designed to be "friendly and humble", while Microsoft's Cortana is described as "not bossy, eager to learn".

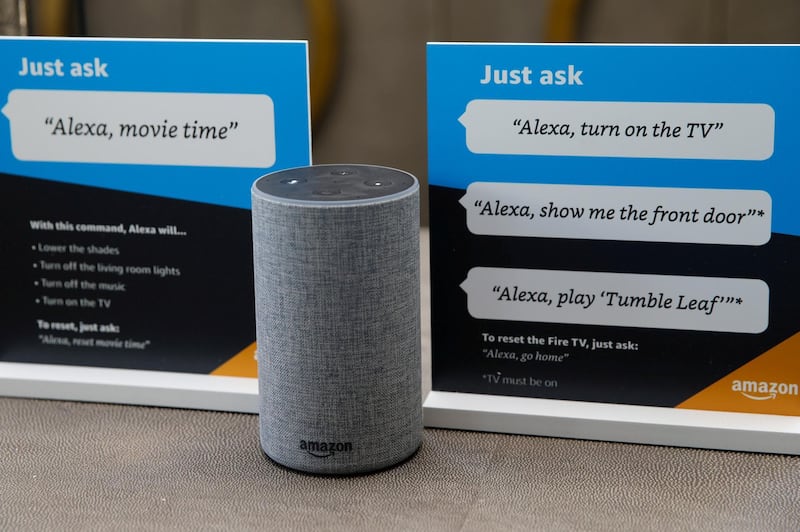

But regardless of these nuances, their voices are predominantly female. Siri and Google Assistant do allow male-sounding voices as an option, but they default to female in most languages. Cortana and Amazon's Alexa are female, too, with no choice offered. According to an Unesco report released last month, this design trend may be reinforcing real-world bias and prejudice against women.

The rise of virtual assistants

Virtual assistants started life as intriguing playthings on our mobile devices, but they are taking on a growing role in society, from booking our travel to assessing our health. To maximise their appeal, they're carefully designed to appear to work for us, obediently, for free. "At the core of design is the idea that you're not supposed to surprise people," says Chris Brauer, Director of Innovation at Goldsmiths, University of London.

"Surprising people makes them uncomfortable, so you try to create predictable things. As a result, female voices tend to appear in bots used in elderly care, hospitality and administrative roles, while in paralegal services and finance they will be male. The bot landscape is merely manifesting existing gender biases in the real world."

Tech companies that have dared to challenge these biases have come unstuck. The Unesco report highlights the example of a BMW vehicle launched in the late 1990s that was equipped with a female-voiced satnav, but ended up being recalled "because so many drivers registered complaints about receiving directions from a 'woman'". Female voices are, however, deemed appropriate for virtual assistants and in the eight years since the launch of Apple's Siri, this design trait has become widespread. Unesco says images that people draw online of Alexa, Siri and Cortana are mainly "of young, attractive women", while the fictionalised virtual assistant that featured in the 2013 Spike Jonze film Her was alluring enough to become a love interest. The idea that virtual assistants are passive, compliant and female has become firmly established.

Why female voices are a problem

The Unesco report outlines a number of reasons why this is problematic, beyond mere stereotype. The abilities of virtual assistants are, at present, highly limited and their responses tend to be vague and simplistic. This is a design necessity to distil complex information down to facts that are easy to announce, but as a result they also make, as the report puts it, "dumb mistakes". By returning wrong answers and misunderstanding queries in an upbeat female voice, the artificial intelligence projects itself as eager but fallible. The report says this leads to a subconscious association between "dumb mistakes" and female voices, thanks to our often-observed tendency to emotionally respond to computers as if they were human.

That tendency threatens to become greater as virtual assistants gain more lifelike qualities. We might find ourselves saying "please" or "thank you" when we don't really need to – or, more likely, express genuine anger at them when they fail to do our bidding. But if we happen to be rude to Siri, Alexa or Cortana, the female voices never chastise, they merely deflect, and Unesco warns of a possible link between our curt treatment of AI and the treatment of people. "The increasingly blurred perception of 'female' machines and real women carry real-life repercussions for women and girls in the ways they are perceived and treated, and in the ways they perceive themselves," it says.

Jonathan Gratch, director for Virtual Human Research at the University of Southern California, says he believes it's difficult to measure the effect bots being gendered as female has on society. "It's certainly valid to raise, though more difficult to establish," he says. "By analogy, it's similar to the question of whether violent movies and video games create a violent society."

But Brauer says what is clear is that emerging data that shows how badly we treat female virtual assistants in private is indicative of a strong undercurrent of gender inequality. "It's been happening in environments that we haven't been able to see," he says. "But now that these systems are in place it's clearly visible. We could change bot design to facilitate an improvement, but that's a responsibility these systems would need to take on."

So what's being done to combat the issues?

The response of technology companies to these issues tends to be one of denial. This even extends to the assistants themselves. When asked which gender they are, they tend to equivocate; Google Assistant cheerily announces: "I'm AI software, so I'm neither!" But Unesco says these bots clearly present as female in both tone and text. "The trend is so pronounced that focus groups find it unsettling to hear a male voice reading a female script, and consider it untrustworthy," the report says.

Brauer says this faithful reproduction of society's stereotypes is happening for one reason. "It's to sell us more stuff," he says. "That's the aim of the system. It's not meant to evolve mindsets, or to help us learn. But if it's not appropriate to ask the corporations who design these systems to take on these issues, then whose responsibility is it?"

Unesco has now called for the creation of virtual assistants that "do not aspire to mimic humans, or project traditional expressions of gender". There has been some work done in this field already; in March, Danish researchers created a genderless voice – which they called "Q" – specifically for use in virtual assistants (you can hear it at www.genderlessvoice.com). But at present there's little incentive for technology firms to change their approach. "Perhaps a broader regulatory landscape needs to be in place to encourage equality and diversity across the landscape of human-computer interactions, but regulators are historically unable to keep pace with changes in technology," says Brauer.

Gratch says the trend for creating human-like bots may one day be reversed if consumers become frustrated at their inability to accurately realise human characteristics. But in the meantime, that frustration is being borne by bots with female voices and Unesco suggests that the "repercussions of these gendered interactions" are only now beginning to come into focus.