The February 14, 2019, car bomb in Pulwama was the deadliest since the start of the insurgency against Indian rule in Kashmir began three decades ago. But, there was another bomb in Pulwama that never went off. The one that could have killed me.

I was a young boy, aged about 12, and was accompanying my parents to a relative's place in the saffron town of Pampore. It was late autumn, in the mid-1990s. A joyous saffron harvesting season was crackling in the village, as the undiscovered bomb kept on ticking.

One day, while we were staying with my relatives, a man arrived at the door, begging for alms. I was told to fetch a bowl of rice for him from a container in the kitchen. As I reached in, I felt the grains of rice, along with a more granular, stony object. It was a hand grenade, which I know now, but then I did not.

The object poked at my childish curiosity. I held it. I flung it between my hands like a little juggler. I called upon the strength of my spindly little arms to remove its rusty pin, which wouldn’t budge. Now, I look back, and I don’t want to imagine what could have happened if the grenade had gone off in my bare hands. The two-storey house had me, my parents, my siblings, all my cousins, my aunts and uncles and a motley group of friends and neighbours inside it. I owe a lot to that stubborn grenade pin.

It’s a memory that reminds me so much of my beautiful Kashmir, a place I call home. Kashmir is also counting on its bruised luck, every day, as it waits for nuclear-armed India and nuclear-armed Pakistan to pull away its pin.

We were close to a war last week. If it hadn't been for the return of wing commander Abhinandan Varthaman, the Indian pilot captured by Pakistan, it could have been a reality. His fateful crash landing into Pakistan after his jet was shot down was like a miracle for the Kashmiris. His safe return to his country, dressed in a seamless navy-blue blazer, finally brought down the fever of a four-day war hysteria, and saved us and the region the agony of a conflict nobody can afford. At least for now.

There was a moment when the captive Indian pilot was asked by a Pakistani soldier if he liked the cup of tea he had been offered. The pilot replied, smiling, and said "The tea is fantastic, thank you". I had a sinking feeling as I watched this unfold on TV. Here was an Indian soldier who, until a little while ago, was on a mission to kill his enemies, but was now momentarily befriending them, even it was just for the cameras. It's this kind of absurdity and irony that's characteristic of the India-Pakistan relationship Kashmiris have been caught in the middle of since the 1947 partition created the two separate dominions.

Srinagar: growing up in the shadow of conflict

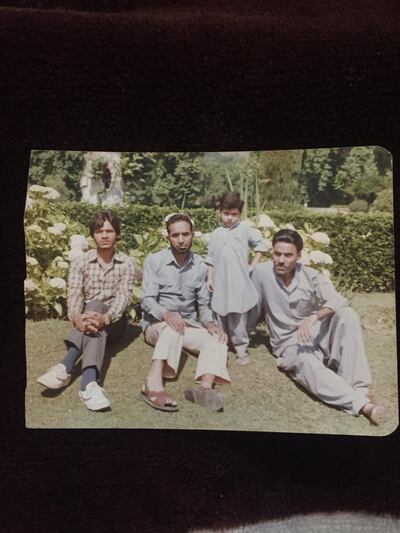

I grew up in the city of seven bridges. Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir, is an old place, with old wounds. I can vividly recall, as would most Kashmiris born in the 1980s, what growing up in the shadow of conflict was like. Today, I wonder how it shaped our psyche.

Now, when the self-appointed foot soldiers of India’s right-wing nationalist party demand obedience of a Kashmiri, they forget the history of abuses the troops have historically imposed. And then Kashmiris are asked to fall in love with India.

Watch: a history of Kashmir dispute

In the aftermath of the Pulwama attack, hysterical mobs attacked Kashmiri students who are studying across different parts of India. These incidents portray a general feeling in the country, which shows they want Kashmir minus Kashmiris.

And, why not? Kashmir is exceptionally beautiful. Away from the arid heat of the Indian plains, it provides a cosy backdrop of four seasons for millions of Indian tourists. It has lots of water that feeds into India's hydroelectric grid. And has huge snow-capped mountains that are a natural bulwark against Pakistan.

But, where does a Kashmiri fit in among all this? More than half a million Indian troops are stationed in Kashmir because Kashmiris, for three decades, have been asking the same question: what about us?

To explain how this question has variously manifested over the years, depends on where you want to start. For me, I remember one morning, in the spring of 2002, when there was an announcement in our neighborhood that the Indian Army had laid a cordon. They were after a group of rebels, they said. I was afraid. All of the men in the area were asked to step out of their houses, while women and children were told to stay indoors. We were soon gathered in an open area.

The soldiers asked young men to step forward. Some of us were randomly chosen to go with them. I was one. It was terrifying. We had no idea if something nasty was going to happen to us. The soldiers soon gave us our task: we were told to go inside a group of houses that lay on the edge of our town. They thought there were gunmen inside those houses, so one officer instructed me to “go inside. If you see them, just wave at us.”

I went inside one house’s courtyard. It had a small, one-room outhouse. I was shivering but made my way towards it, anyway. There was nobody inside, but there was a large mound of husk left for drying and one pair of flip-flops popping out from the top of the mound. So, I waved at the soldiers.

When I look back at this incident, I always have this ghostly feeling that there was somebody hiding inside the mound of husk. It is stories such as these that have shaped a Kashmiri's relationship with India, and the world is surprised why they haven't fully embraced the world's largest democracy.

Being pushed to the brink of madness

India has failed to make Kashmiris fall in love with it. Its soldiers have failed to make Kashmiris fall in love with their country. Not that it was the soldiers' job to shower love on Kashmiris in the first place. In the past three decades, about 70,000 people have been killed in Kashmir. Thousands are missing. Hundreds have been blinded by pellet guns. In 2017, a Kashmiri man was tied to the top of a military jeep. Farooq Ahmad Dar, a shawl-weaver, was made into a human shield by the Indian Army. And to add salt to the festering Kashmiri wounds, the officer who dragged him as a trophy, in an ugly display of wanton force, was awarded a medal by the Indian government.

It is not just the cold statistics of Kashmiri killings, but these extravagant displays of military muscle by India that has pushed the place to the brink of madness. The whole of the ’90s played out to a backdrop of armed insurgency in Kashmir, openly supported by Pakistan. Those armed asked the same question: what about us?

In the '90s, we were alone. There were no phones, no internet. Those ominous days when the thud of military boots grew louder and louder, a Kashmiri couldn't tell his story through social media. All of the stories of injustice died in that dark, unconnected, silo.

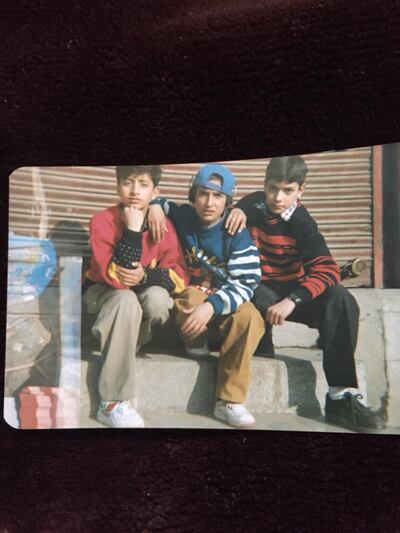

In the '90s, thousands of Kashmiri boys ran away to cross the high mountains into Pakistan to get arms training and return to fight the Indian troops. For those of us who were kids, it was thrilling to see those big boys with big guns. We would follow them into the cobblestone streets of Srinagar, until they would disappear into some shady by-lanes. India soon brutally crushed this armed rebellion. Then it was eerily quiet until 2008.

The black and white binary picture painted of Kashmiris

In 2008, I was a young intern in one of India’s top TV news channels based in New Delhi. That’s when I found myself editing a video clip that came from Srinagar. Protests had broken out. Young Kashmiri men were pelting stones at the Indian troops. In the clip, amid the smoke of tear gas, a silhouette of a young Kashmiri man was making what my editor told me were vulgar hand gestures towards the troops. It was a poignant realisation that Kashmiris had moved on in how they wanted to fight. The gun had been replaced by a stone. But they were still asking: what about us?

When I recall these memories, and ask why Kashmiris are made into such villains merely for asking for their rights, I see two prominent anti-heroes: India's Bollywood and its fervent, nationalist media are equally to blame. While most Bollywood movies end up showing the world a cherubic, pastoral Kashmir with roses and lilies blooming on its verdant hills, a Kashmiri is often reduced to a shadowy figure who is either a terrorist or supporting one.

The same is seen through India's media. Over the years, it has reduced a Kashmiri to an apologist who is forced to pick from two options: hail India or death to Pakistan. In this shallow, black and white narrative of binaries, nobody asks the original stakeholders: what about you?

And whenever a Kashmiri makes a murmur to answer this question or attempts to talk about India's injustices in the valley and the disillusionment and anger it has brought, it is confused, and often sugar-coated, and taken as his desire to join Pakistan. It is not.

What about the future? What about Heeba?

If you fly over the Kashmir valley, it looks like a bean-shaped sliver in the middle of the lofty Himalayas. If aliens were to fly by, they wouldn’t even pay attention to this small piece of land wedged between the three big countries: India, Pakistan and China. It is only when you set foot in it, that it grabs you – first by its sheer beauty and then by the oppressive air within its borders.

I have been away from Kashmir for at least a decade now. But every time I go home, almost once a year for a few weeks, I feel the usual air of siege. Since January 2018, nearly 600 people – including civilians, militants and soldiers – have been killed.

For me, the face of Kashmir’s unsolved dispute is found in 19-month-old Heeba. Last year, this Kashmiri toddler became its youngest pellet-gun victim. After a battle with Kashmiri rebels, Indian troops shot multiple pellet guns to disperse the protesting crowd. They also fired tear gas. At her home, Heeba’s mother couldn’t bear to see her children choking in smoke that had been snaking into their house. So, together, they ran outside to find shelter. That’s when Heeba got shot in the eye.

When Heeba grows up, should we ask her why she didn’t fall in love with India?

Jammu and Kashmir: the story behind the conflict

Katy Gillett details the history of the troubles

In 1947, following the British Empire’s exit from British India, and the formation of the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan, a partition plan provided by the Indian Independence Act left Kashmir free to accede to either nation. The maharaja, Hari Singh, chose India. It was an unpopular choice with Pakistan that led to a two-year war.

The matter finally went to the United Nations, which said a referendum should be held to decide Kashmir’s future, but neither India nor Pakistan has ever allowed it. When the war ended in 1949, the UN-backed ceasefire thensaw Kashmir split into a Pakistan-administered zone and an Indian-administered area.

A second war between India and Pakistan broke out in 1965, when the Pakistani Army attempted to take Kashmir by force. They were unsuccessful, and a stalemate was reached. in the Ind ia o-Pakistan War.

A ceasefire remained in effect until 1971’s Indo-Pakistani War, which began in December, spurred by India’s involvement in the Bangladesh Liberation War, or Pakistani Civil War. India supported the Bangladeshi bid for freedom, and opened its borders. A build-up of Indian forces on the border with East Pakistan ultimately led to a third war over Kashmir. It lasted less than two weeks, as Pakistan was defeated and the 1972 Simla Agreement turned the Kashmir ceasefire line into what is now known as the “Line of Control”.

In 1987, in Indian-administered Kashmir, disputed state elections gave rise to a pro-independence insurgency. From 1990, this escalated, and violence supported by both sides was commonplace throughout the decade. In 1999, the Kargil War took place between the two nations in Kashmir’s Kargil district. By this point, both India and Pakistan had declared themselves as nuclear powers.

The early 2000s were marked by a push and pull between peace and violence. Moves were made to boost national relations, but violence was still a reality. By 2008, major protests had erupted, and flare-ups have occurred regularly in Indian-administered Kashmir in the past decade.

In 2015, a coalition between India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the local People’s Democratic Party was formed. In June 2018, the BJP pulled out, leaving the state under direct rule from Delhi. This added more fuel to an already-burning fire.

The spark to a new armed rebellion came in 2016 after the death of the young Kashmiri rebel commander, Burhan Wani. He had a vast following on social media and his death became a watershed moment. Hundreds of Kashmiri youths joined militant ranks to fight the Indian rule.

In 2018, the death toll among militants and security forces reached its highest in a decade, with more than 320 killed.

Most recently, on February 14, 2019, 40 Indian soldiers were killed by a suicide bomb in the deadliest attack Kashmir had seen in three decades. India blamed Pakistani militant groupsfor the attack, and on February 26, it launched air strikes into Pakistani territory. It looked as though another war was about to break out, but when Pakistan safely returned an Indian pilot shot down over Kashmir, the clash de-escalated. As India is soon to go to the polls, the story behind the conflict continues.