The more we communicate, the faster the English language changes. It won't have escaped anyone's notice that the 10 years we've just lived through was the first full decade of the smartphone and of social media, two innovations that prompted us to find new ways of expressing ourselves. We did so with new euphemisms, slang and abbreviations; by bending grammar into different shapes and using pictures to enhance meaning. These kinds of changes are always resisted by traditionalists, but it's part of a perfectly natural evolution. "If a community of speakers is using a word and knows what it means, it's real," says professor Anne Curzan in a Ted Talk. "That word might be slangy, that word might be informal … but that word that we're using, that word is real."

Many words have come into popular usage to represent inventions appearing in the world around us. The first consumer drone appeared 10 years ago. Few people knew what Bitcoin was in 2010, let alone fidget spinners. Fracking and vaping became commonly used verbs, contactless payments went from rare to everyday, and people began sporting onesies, manbuns and athleisure clothing.

We found ourselves indulging in new activities that needed new words to describe them: taking selfies, binge-watching TV series and ghosting people we no longer wanted to be in touch with. We saw the rise of the Scandinavian lifestyle trend known as hygge, the pursuit of squad goals, wealthy start-ups referred to as unicorns, and the (dreadful) word nom being used to describe something tasty.

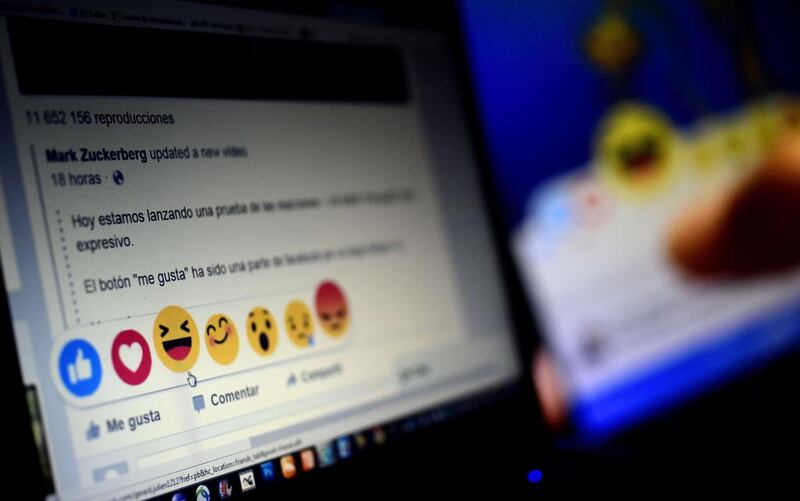

But perhaps the biggest shift in communication in the past decade has been the popularisation of the emoji. In October 2010, Unicode, the consortium that decides the world's standards for computer text, established the first set of 722 emojis. From then, as far as online communication was concerned, emojis were on a par with the traditional Roman alphabet and they quickly became indispensable. In 2015, Oxford Dictionaries' Word of the Year was an emoji – the Face With Tears of Joy one – much to the horror of language purists. But emojis can be more complex than they appear. By the decade's end that symbol had gained many meanings, including derision rather than delight. Gifs became another popular tool of expression, with ironic conversations conducted via short animated sequences from popular films and TV shows.

This yearning for brevity also yielded a new batch of abbreviations and acronyms. Ask Me Anything (AMA) became one of Reddit's most popular communities, while ELI5 (explain like I'm five) became shorthand for needing to have something clarified as simply as possible. Yolo (you only live once) became a rallying cry, and Fomo (fear of missing out) was the social media-induced feeling that everyone else was Yolo-ing and you weren't. About halfway through the decade we saw the emergence of Doge, a picture of a shiba inu dog with some grammatically dubious captions in a Comic Sans font (for example "So scare"). No meme has had such a profound effect on online grammar; from then on, awkward two-word combinations were instantly understood for what they were. Such amaze. So respect. Much wow. Meanwhile, another video meme by a Chicago woman describing her perfect eyebrows gave us the phrase on fleek. And it hasn't gone away yet.

The often bizarre developments taking place in online communities required dozens of words to describe what was unfolding. Trending may not have been a new word, but it gained new meaning around 2011 as various topics surged to prominence on social media. Humblebragging (2011), catfishing (2013) and photobombing (2014) all made it into various Word of the Year lists. As the technology around us slowly changed, we became familiar with adblockers, chatbots and, if you dared, the dark web. More recently, the impact of charismatic youngsters on YouTube and Instagram gave birth to the term influencer, and attempts to dislodge them from their pedestals by accusing them of questionable behaviour was an example of so-called cancel culture.

The intensity of online discourse brought new terms to prominence such as mansplaining and incel. The most resonant hashtags of the decade were #BlackLivesMatter (dating from the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman for the shooting of Trayvon Martin in Florida) and #MeToo, following the sexual abuse allegations against film producer Harvey Weinstein. One political wing found itself labelled as the alt-right, another as Antifa. Many people were accused of being woke for showing too much sympathy with progressive causes, and others of cakeism (stemming from the phrase "have your cake and eat it"). Occupy, Brexit and Youthquake all found themselves in the news as social change unfolded around us.

The election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016 had a curious impact on language. His fondness for communicating directly with the public via Twitter, and the enormous attention bestowed upon those tweets by the media, meant even his slip-ups entered lexicon (for example "Covfefe", from a tweet in May 2017, an apparent mistyping of coverage.) But his dismissal of unfriendly media as "fake news" was the dawn of an era in which any position could be adopted and any opposition refuted, as long as you did it brazenly and boldly enough. As black was stated to be white and reality openly doubted, words such as post-truth, gaslighting and deepfake were used with increasing frequency.

But amid all the unsettling changes that can make our world feel so disorientating, there has been plenty to lighten the mood. South Korean singer Psy gave us Gangnam Style, and was subsequently recognised by the UN for his skill of dancing as if riding a horse. Twerking wasn't recognised by the UN, but everyone now knows what it is. A 16-year-old American schoolboy, Russell Horning, became famous for flossing, and it wasn't long until the world was flossing, too.

Ten years ago, none of this would have made any sense. But making sense of our world is what an ever-changing language is all about.