What do we really know of Cleopatra, the tragic final pharaoh of Egypt who seduced the two most powerful men of her era, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, and struggled to protect her empire from Roman domination?

Over the centuries countless creative works have fed the myth of the femme fatale and obscured the historical facts.

"Pretty much everyone thinks they know about Cleopatra, but they don't really know who she was at all," says David Nixon, the artistic director of Britain's Northern Ballet and creator of Cleopatra, a new full-length piece of dance theatre. "And that provides a choreographer with a great deal of scope." His aim was to get closer to the real Cleopatra.

"We don't even really know what she looked like or if she was actually a great beauty," he says. An Egyptian coin is the only confirmed image of Cleopatra, though a bust in a Berlin museum shows a woman who may be Cleopatra with her hair in the popular Roman style of the era.

And yet some of the most beautiful actresses of stage and screen have been cast to play this beguiling woman - stars such as Claudette Colbert and Elizabeth Taylor.

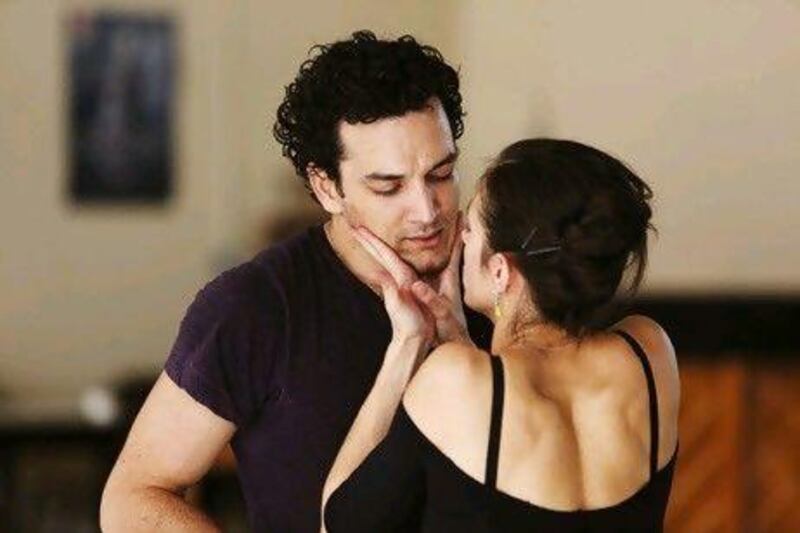

In the Northern Ballet production, a newer beauty plays the Queen, the American ballerina Martha Leebolt. Nixon built the ballet around the 28-year-old. Leebolt, who moved to Britain 10 years ago from her native California, has just won the award for Britain's Outstanding Female Ballet Performance by the Critics' Circle National Dance Awards of the United Kingdom. She sees Cleopatra as her career high point.

"What an amazing story," Leebolt says. "She is such an iconic woman. You couldn't really ask for a better part to be created on you - to have Cleopatra be your ballet. She was such a strong and powerful woman, especially for her time when men ruled everything. To be able to play such a commanding woman on stage is hard, but is really rewarding."

The music is by the French composer Claude-Michel Schönberg, whose successes include two international hit musicals, Miss Saigon and Les Misèrables. He first worked with Nixon 10 years ago when the Canadian choreographer took over as artistic director of the Northern Ballet.

The company is based in the Yorkshire industrial city of Leeds. Cleopatra is its first new ballet for two years and is touring Britain until the end of May, and will return for a short run this autumn. Nixon, one of Britain's most prolific choreographers, was awarded an Order of the British Empire last year for his work with the company and its dance academy.

Nixon and Schönberg's first collaboration was Wuthering Heights, originally intended for another dance company.

"I was quite new to the job and the chief executive said he had been sent this CD of a score for Wuthering Heights by Schönberg," Nixon says. "At first I was a little bit... I said, 'Well, who's that?' And he said, 'He is just the composer of Les Misèrables and Miss Saigon.' I thought, 'Oh my God!' Les Misèrables was my absolute favourite musical. So I listened to it and it was really beautiful music."

It was a big success and afterwards the two men agreed to collaborate again. Nixon had been nurturing the idea of a ballet about Cleopatra for some years. But the first scenario commissioned, from a German dramaturge, didn't work. The idea was put aside.

A decade later Nixon revived it and worked quietly with Schönberg before bringing in the company's long-term co-director, Patricia Doyle, to help rethink the story structure.

Schönberg became enthusiastic. He says: "When you talk about someone like Mother Teresa, you don't imagine her on stage, but with Cleopatra it is easy to imagine seeing her danced on stage. I wrote 10 minutes of music. He listened and loved it and I kept going and wrote and wrote music and so he surrendered and said, 'I am going to do it'."

So with a musical score and the lead dancer decided, Nixon had to grapple with translating the complexities of the history and the myth into a compelling piece of ballet theatre.

Cleopatra VII was a member of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since the death of Alexander the Great. Her wider fame came after she began romances with Julius Caesar, with whom she had a child, and after his murder with Mark Antony. This was her undoing. After losing his rebellion against Rome, Antony killed himself. Cleopatra then ended her own life, famously by clasping a snake to her bosom.

The West has focused on this romantic tragedy, largely ignoring her struggle to preserve a dynasty and an empire. But Medieval Arab scholars often referred to her as "the virtuous scholar", according to the London-based academic Dr Okasha el Daly, and marvelled at her intellectual prowess - a mastery of alchemy, philosophy, mathematics, languages and even town planning.

In re-imagining Cleopatra, Nixon and Doyle did extensive research. So did Leebolt.

"There is a lot of information, but how much is really concrete? There are a lot of myths," Leebolt says. "So in preparation I read a lot and saw as many films about her as I could. Even looking at pictures can get your mind going. You make your own character by taking information from so many different places. I became really intrigued with her. You wonder how she did what she did - to rule Egypt and have love affairs with the two greatest men of her time? She must have been very intelligent. She must have had more than just her sexuality to achieve what she did."

Nixon says: "I don't think beauty alone could sustain her fame for 2,000 years. To hold these two powerful men in her hands, there must have been much more. They must have felt she was equal in many ways or perhaps even superior. For me Cleopatra is epic, like Alexander the Great. She had qualities above the normal and that includes intelligence. She spoke between seven and 11 languages and was trained as an orator and she would have used her training in how she spoke to these people. She was certainly more educated than Mark Antony, possibly more than Julius Caesar. And at the same time, she was a woman, a mother and a lover. Although she is often portrayed as a whore, there is no evidence she was unfaithful to either of them."

Getting to the truth about Cleopatra has challenged scholars for centuries. The Roman poet Horace first created the notion of her as a great seductress, and the popular perception of her has been dominated by William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw's great plays about her love life.

The first account of her life was written by the Greek Plutarch 200 years after her death. There are only a handful of accounts by people who actually met her and their objectivity is doubtful.

The newest biography of Cleopatra is by the American writer Stacy Schiff, who says she deserves to be remembered not as a sexual adventuress but "as the sole female of the ancient world to rule alone and to play a role in western affairs".

But Schiff adds: "She descended from a long line of murderers and kept up that tradition." Cleopatra was one of six siblings. Her father killed the eldest and Cleopatra was behind the death of the others.

Schiff says that by the standards of her time Cleopatra was fairly well-behaved. If the Romans had not defeated her, her own son might eventually have plotted her killing.

Nixon's ballet doesn't avoid this darker history. There is a graphic portrayal of her killing of the brother with whom she jointly ruled. Nixon says he wanted to tell the story of her whole life, not simply offer another version of the love story.

Leebolt says: "Cleopatra was willing to do anything to be Queen and take care of her country. There are parts about her you do admire because she is so strong, but parts you certainly don't want to have in your own character."

How do you compress such complexity into dance, which must tell its tale through movement, gesture and music without words?

Nixon says: "You can't get everything across in a ballet over a couple of hours. The point of the piece was to give an overview of her. From that we arrive at the legend. We get the differences in her loves, that she is a woman who knows grief and sorrow and success. We get elements of her intelligence through the decisions she makes. We have given her the premonition before the Ides of March. She sensed the mood of the people and she was very protective of her child and she had to flee when things went wrong. I never profess that in dance we can tell everything, but it is the physical image of a woman in movement that captures something extraordinary - and in dance you can capture that element of Cleopatra better than in any other genre."

The production draws heavily upon Egyptian iconography. Leebolt adds: "A lot of the Egyptian characters use vocabulary in their movements that is slinky and fluid with hand gestures drawn from hieroglyphics. But not too much otherwise it would be clichéd. The Egyptians are very fluid and the movement never ends. The Roman men are much sharper and more angular."

Cliché is also avoided in the music. Schönberg eschewed familiar dashes of Orientalism in his score or the use of trumpets and brass for the Romans.

One of the ballet's most remarkable devices is to turn the snake the Queen used in her suicide into her personal god Wadjet, who tracks her from the beginning to the end of the play - a remarkable performance of serpentine sinuosity by the young Scottish dancer Kenneth Tindall.

The company went into rehearsal with Cleopatra at the beginning of this year after a visit to China. The first night was in Leeds in late February. Now the company is on the road with the show - an entourage of around 100 people.

For Leebolt 2011 will have been the year of Cleopatra, and she has no real sense of what role comes next. The life of a dancer is tough and injuries common. But the emotional commitment is equally intense.

"This is an exhausting role," she says. "You are on stage almost all the time and for all of the weeks of rehearsal and performance you eat, breathe and sleep Cleopatra - 100 per cent Cleopatra. On stage I am in Egypt and at night I dream about it. You have to live it."