A glamorous Cinderella is swept off her feet by a dashing gentleman, much to the consternation of the onlooking, envious and remarkably evil stepmother. But look again, and this heart-throb is not quite the bow-tied Prince Charming of legend. He is Harry, a pilot smartly dressed in uniform. We're at not a lavish ball in a sprawling mansion, but a Second World War dance in the UK during the Blitz. Meanwhile, Prokofiev's score is competing for attention with air-raid sirens and searchlights.

This, then, is no ordinary Cinderella ballet. But the choreographer Matthew Bourne's dazzlingly inventive relocation of the classic fairy tale to 1940 - which played to full houses last week at The Lowry in Greater Manchester and transfers to Sadler's Wells in London for a two-month run this week - makes sense. Cinderella ballets may usually be full of traditionally grand waltzes, but Prokofiev wrote the score during the Second World War. Bourne says in the programme notes: "Was this dark period in our history somehow captured within the music? I felt that it was, and the more I delved into the Cinderella story, it seemed to work so well in the wartime setting."

So he embarked upon fashioning a darkly romantic ballet, set in an era when love was suddenly found and cruelly lost, when time was everything. When, as Memphis Belle so evocatively portrayed on screen, the world danced as if there were no tomorrow. But such an approach does raise one question: should the classics be continually bent in this way to fit the whims of choreographers or film directors?

Bourne is one of the world's pre-eminent choreographers. His version of Swan Lake, which is also set in modern times and replaces the traditional corps de ballet with a male ensemble, garnered worldwide acclaim. So it's fair to say the future of ballet is safe in his hands. But there can be dangers in arbitrarily updating the classics.

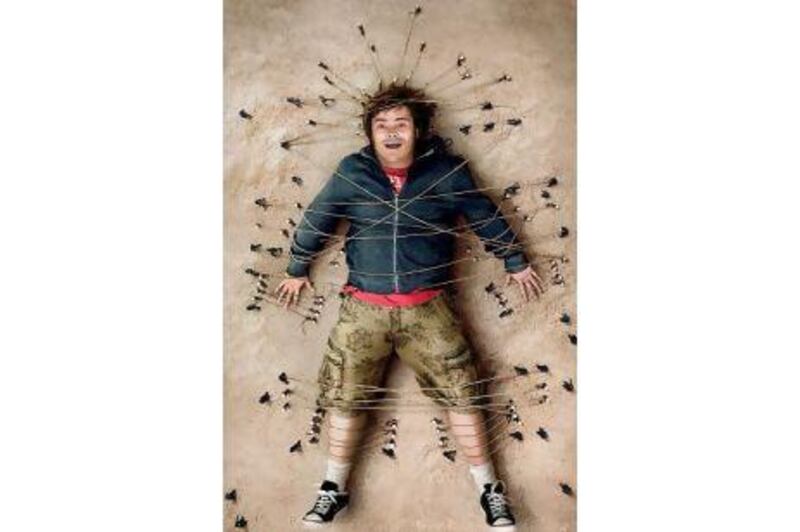

Next month, Jack Black plays the title role in a film adaptation of Gulliver's Travels, the 18th-century novel by Jonathan Swift. In the book, Gulliver is shipwrecked and finds himself in the middle of a conflict between the islands of Lilliput and Blefuscu, both inhabited by people less than 15cm tall. It's widely regarded as one of the cleverest, most satirical novels of its age. In the 2010 film, though, the trailers suggest that not one iota of that intelligence has survived the adaptation. The director of Shark Tale and Monsters vs Aliens may be within his rights in updating it, but one wonders what kind of person will be drawn to a film where the "hero" puts out house fires by urinating on them.

And while some might argue that there's nothing wrong with being so irreverent with the source material, particularly source material that's out of copyright, the real problem with treating Gulliver's Travels in such a cavalier way is that it won't encourage a new generation of readers to discover the book for themselves.

One of the most impressive and successful modern adaptations of recent times was Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, where the Montagues and Capulets were warring business empires and guns replaced swords. It looked stunning in its contemporary setting, and Luhrmann kept Shakespeare's dialogue intact.

Luhrmann's success with Romeo + Juliet in the mid-1990s was part of a wave of literary movie adaptations that updated the setting to high schools but retained the character of the originals. The superb Clueless, Alicia Silverstone's breakthrough film of 1995, was drawn from Jane Austen's Emma. Cruel Intentions, starring Sarah Michelle Gellar and Reese Witherspoon, was a 1999 take on Les Liaisons Dangereuses. And in the same year, Ten Things I Hate About You was an admittedly loose but nevertheless rather enjoyable version of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew.

Since then, the likes of Romeo Must Die and Ethan Hawke's Hamlet have hardly covered themselves in glory. But this year, the bar was raised once again by the wonderful Easy A - an update of Nathaniel Hawthorne's 19th-century romantic novel The Scarlet Letter.

The successful films are unquestionably those that respect the source material. After all, there is a reason why the classics are timeless. They speak not just to the people of the times in which they were written, but deal with issues and feelings that resonate across the centuries - love, war, family and friendship. The key to modernising them is to make the setting fit the story, rather than the other way around. So Cinderella works in the Second World War because it's a coherent, clever and illuminating backdrop. Poor old Cinders might be cowering behind the blackout windows, but she still wants to go to the ball.

Indeed, once Bourne knew it could work, he really went to town. There are also nods in his Cinderella to the classic mid-20th century films which match the ballet's atmosphere of longing and regret. So there's more than a hint of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1946 romantic fantasy A Matter of Life and Death, which starred David Niven. David Lean's Brief Encounter (1945) is also referenced in the final railway scene.

The result is a ballet that should genuinely convert newcomers to the form. And bringing classics to new audiences in exciting and innovative ways should always be the real motivation for those who would dare to take on some of the cornerstones of literature from across the centuries. Money-grubbing updates are about as welcome as, well, an evening out with the ugly sisters.