"I've always responded to the history of my times," declares the protagonist of E L Doctorow's slippery and beguiling new novel. It is an avowal that could double as a mission statement for Doctorow's fiction over his 50-plus-year career. The Book of Daniel (1971), an account of the Rosenberg atomic secrets conspiracy, is his most famous book that deals with that history – specifically that of 20th-century America. But Doctorow doesn't confine himself to epochs he has lived through. Ragtime (1975), perhaps his most-loved book, charts family tensions in the run up to the First World War, and The March (2005) harks even further back to the final days of the Civil War.

Each time, Doctorow appropriates a historical setting or drama and employs a cast of largely fictional characters to re-enact it.

Which makes it all the more surprising to find Andrew's Brain a marked departure from this standard practice. Instead of an allocated time and place, Doctorow takes the reader into the mind of a man and "the depthless dingledom" of his soul, exploring his life in all its tragedy and analysing how his brain has functioned.

The novel opens with a short but stunning scene. A man called Andrew knocks on his ex-wife’s door one snowy evening and presses upon her his new baby, imploring her to look after it.

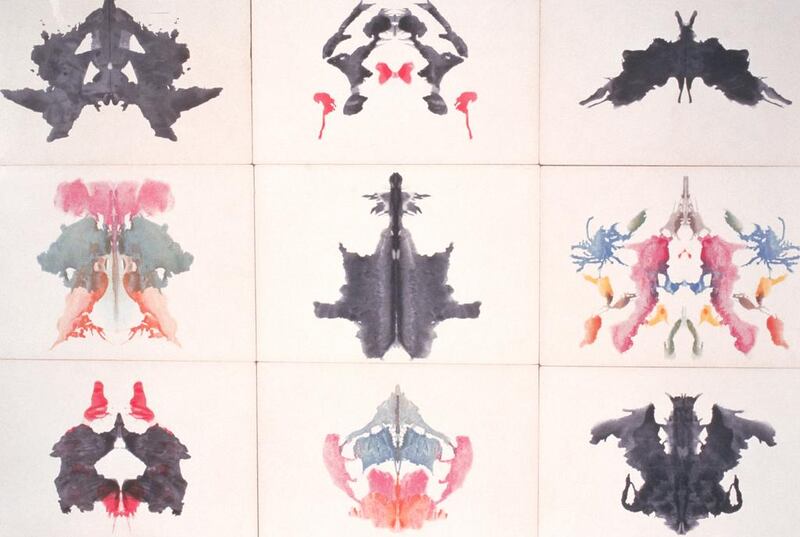

Doctorow teases us by bringing in another speaker and dropping some clues – “talking cure”, “hearing voices” – from which we extrapolate that Andrew is a patient unloading his soul to a psychotherapist. Here and there we get a kind of reciprocal stupefaction – Andrew griping at his interlocutor’s obtuseness; the interlocutor recoiling at Andrew’s no-holds-barred confessions – but otherwise the conversation flows, with one man eliciting, the other volubly responding.

Andrew takes us back, explaining how his marriage to his first wife imploded when he accidentally killed their sick child by administering the wrong medication. He slinks off into self-exile, losing himself in teaching jobs. One of his Brain Science pupils captivates him and, following a professor-student affair, they settle in New York and have a child. However, Andrew’s redemption is short-lived. She disappears without trace on 9/11, leading a desolate Andrew to hand their child over to his ex-wife as a replacement for their dead one.

Bound up in this chain of events are Andrew’s childhood reminiscences, diary extracts and his “adventures with the race of women”. We encounter vaudeville dwarfs and a drunken opera singer in full czarist regalia. Dreamscape frequently encroaches upon reality, prompting the analyst to check whether Andrew has stepped over the line.

More so, though, science impinges upon reality, with Andrew dilating on consciousness and other mind-matter, and decoding and deconstructing the thoughts that led to his deeds. He is a cold customer, a self-professed man without feeling, able only to summon “a faint tinge of regret for dead babies, dead wives, for the fires I’ve inadvertently started”.

This clinical recourse to rationalising sounds like little fun, but while Andrew may not endear, his complexity renders him intriguing.

The mystique is heightened towards the end when Doctorow jolts us with the suspicion that Andrew may be an unreliable narrator who has hoodwinked us all along. Did he really share a room at Yale with the future president and later work in the basement of the White House? Where is the boundary between confabulation and deception? "You don't know everything about me, Doc," he sneers, "you're only hearing what I choose to tell you." Not for nothing has his nickname been Andrew the Pretender, and it certainly accounts for the many schizophrenic switches from first to third person. English novelists have had mixed success incorporating science in fiction. Ian McEwan's Saturday and Sebastian Faulks' Human Traces were marred by chunks of cut-and-paste fact and indigestible exposition. American writers seem to do it better, and, indeed, Andrew's Brain wears its research well – smartly standing out but not flamboyantly taking over. The whole book has the feel of Philip Roth at both ends of his career: the story-as-psychoanalytic-session recalls Portnoy's Complaint while the psychological depth condensed into a slender volume is redolent of Roth's last works.

At 83, Doctorow has entered his late period and this tale of a headshrinker trying to interpret mind-expanding truths is simultaneously a surprise turn and a welcome new direction. The scintillating prose remains the same, as do the characters shaped by history or, in this case, dislocated by each new chapter. “Are you traumatised?” the interlocutor asks at one point. “Only by life,” Andrew answers.