Considered one of the highest accolades an author can receive, the Nobel Prize for Literature has awarded an eclectic array of international writers over the last five decades who published various forms of prose ranging from novels memoirs, stage plays to song. Despite their different disciplines their approach to their craft is united over the notion that writing is as about discipline, observance and good old fashioned imagination.

2017 winner Kazuo Ishiguro, author of the novel Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go

"I would, for a four-week period, ruthlessly clear my diary and go on what we somewhat mysteriously called a "Crash," he told The Guardian newspaper in 2014. "During the Crash, I would do nothing but write from 9 am to 10:30 pm, Monday through Saturday. I'd get one hour off for lunch and two for dinner. I'd not see, let alone answer, any mail, and would not go near the phone. No one would come to the house. (Ishiguro's wife) Lorna, despite her own busy schedule, would for this period do my share of the cooking and housework. In this way, so we hoped, I'd not only complete more work quantitatively, but reach a mental state in which my fictional world was more real to me than the actual one. The goal was method writing, essentially: to create an environment, through force of will, in which the author and his story might be merged into one. It was a plan that demanded intentionally de-romanticising the act of writing. Throughout the Crash, I wrote free-hand, not caring about the style or if something I wrote in the afternoon contradicted something I'd established in the story that morning. The priority was simply to get the ideas surfacing and growing. Awful sentences, hideous dialogue, scenes that went nowhere—I let them remain and ploughed on."

2013 winner Alice Munro, author of short story collections Dear Life and Who Do You Think You Are

“Sometimes I get the start of a story from a memory, an anecdote, but that gets lost and is usually unrecognisable in the final story,” she said in supplied interview by publishers Knopf Double Day. “Suppose you have—in memory—a young woman stepping off a train in an outfit so elegant her family is compelled to take her down a peg (as happened to me once), and it somehow becomes a wife who’s been recovering from a mental breakdown, met by her husband and his mother and the mother’s nurse whom the husband doesn’t yet know he’s in love with. How did that happen? I don’t know."

2006 winner Orhan Pahmuk, author of the novels My Name is Red and The Museum of Innocence

“Forty years of devotion to the art of the novel taught me one thing, that is to pay attention to people's lives, to pay attention what you hear about people's lives,” he said in a YouTube video by the cultural organisation The Big Think.” The secrets of writing is rewriting, self-editing, reediting, reading to your beloved ones, to your wife, to your daughter, to your partner and hearing the story from other people's point of view never giving up your high standard of criteria, of good writing, and continuing on and on and on and on and editing and editing and taking out, no matter how much time you gave to that beautiful page, perhaps that can also be cut out.”

2001 winner V.S Naipaul author of the novel In a Free State and the travel memoir Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions among the Converted Peoples.

"Do not use big words. If your computer tells you that your average word is more than five letters long, there is something wrong," he said in an interview with the Indian magazine Tehelka. "The use of small words compels you to think about what you are writing. Even difficult ideas can be broken down into small words.

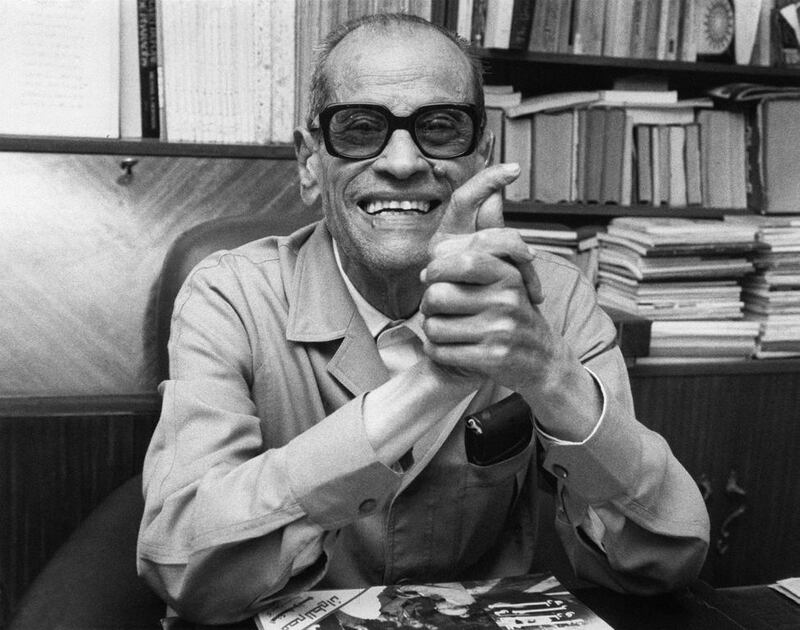

1988 winner Naguib Mahfouz author of the novels Palace Walks and Children of Gebelawi

"When you spend time with your friends, what do you talk about? Those things which made an impression on you that day, that week . . . I write stories the same way," he said in an interview with The Paris Review. "Events at home, in school, at work, in the street, these are the bases for a story. Some experiences leave such a deep impression that instead of talking about them at the club I work them into a novel."

_______________

Read more:

[ Nobel Literature Prize 2017: British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro wins award ]

[ The ice queen thaws: interview with Margaret Atwood ]

[ Leonard Cohen poems to be published in final book ]

_______________