William Gibson coined the term "cyberspace" before any of us knew what the internet was. His first novel, Neuromancer, speculated with such accuracy on the information age now come to pass that he's valued as much as a visionary business consultant as for his literary ingenuity. But since the 1990s Gibson has stopped writing science-fiction, saying that contemporary life has overtaken it for strangeness and technological assimilation and that any story he might want to tell could be plausibly set in the present. The seductive corollary, of course, is that people don't mind being seen reading literary fiction in public. Thus Zero History concludes an exhaustively of-the-moment "branding" trilogy which the author began in 2003 with Pattern Recognition, a novel whose heroine was literally allergic to corporate logos.

Gibson novels typically make original use of the MacGuffin as central plot device and in the present case it's the brilliantly inconsequential Gabriel Hounds label, a "secret brand" who make beautifully designed jeans and jackets, highly sought-after and expensive not least (perhaps chiefly) as a result of their rarity. Having lost a lot of money in the recent market crash, Hollis Henry, former lead-singer of "semi-famous" band The Curfew, once again lends her services to the preposterously named Hubertus Bigend and his marketing agency Blue Ant. Bigend wants to find the secretive designer behind Gabriel Hounds; he's trying to break into military uniform contracting (it's recession-proof) and wants outside help. In an all too plausible feedback loop, the military is trying to compete with the contemporary streetwear it influenced but now lacks the tailoring expertise to replicate. The bitesize chapters alternate between Hollis and Milgrim - a likeable loser emerging from a decade-long "brown out" during his addiction to painkillers - as they embark on Bigend's quest.

Milgrim, having missed 10 years, is a blank canvas, able to ask penetrating questions about the technologies everyone else takes for granted. He isn't the only one making enquiries, though. With military contracting comes federal-agency interest and sinister arms dealers, naturally, and Bigend's crew soon find themselves in over their heads. The resulting wild goose chase takes in Paris and London with a vivid supporting cast of musos, fashionistas, federal agents, Russian gangsters, conceptual artists and deluded co-conspirators. Both Hollis and Milgrim are unsure as to Bigend's motives, even whether he really has any. At one point he is described as a producer "but without the hassle of having to make movies", a dilettante with contacts.

The lightness and self-conscious arbitrariness of all this is, of course, the point. As Hollis reflects listening to the news: "Nothing of catastrophic import since she'd last listened, though nothing particularly positive either. Early 21st-century quotidian, death-spiral subtexts kept well down in the mix." This could describe the whole trilogy. The success of Zero History hinges on its convincing portrayal of the cultural concerns and artefacts of the day: I had never before seen Twitter used as a vital plot device in a published novel, for instance. Further modish references abound - to boutique labels, Ponzi schemes, iPhones, base jumping, darknets, post-skate trainers. This ephemera reaches its climax in the pop-up shop, a temporary clothing outlet which springs up overnight and disappears just as quickly; its appearance signals the novel's dénouement.

What could feel trivial or self-satisfied has an odd ring of authenticity in a world where even a club's toilet paper can been chosen for its "retro" feel. Gadgets are integrated seamlessly into the lives of the characters. Clothes are lovingly described to the point where you can almost feel them and desire them as much as their fictional demographic. Made-up bands (in film as well as literature) are so often embarrassingly crass, blunt satires or glamorisations of some weak simulacrum of an already passé original. It helps here that Gibson knows the world he's talking about - he often collaborates with esoteric groups, wacky designers, performance and visual artists.

Hollis's former band, The Curfew, is an entirely plausible art-punk outfit. Her knowing cynicism is a necessary leavener as she researches Gabriel Hounds: "Everything, she knew, had already been the title of a CD, just as everything had already been the name of a band. This was why bands, for the past 20 years or so, had mostly had such unmemorable names, almost as though they'd come to pride themselves on it." Isn't this how we think now, suffused as we are with adverts and design? Half our brain is always wondering how X might work as a title, a name, a brand.

Gibson's writing is as fine as ever. Browsing through the bric-a-brac of a coastal souvenir shop is "like being on the bottom of a Coney Island grabbit game". Emerging from the channel tunnel, the French countryside appears "as if a switch had been thrown". Even car chases, normally a disaster in prose, are handled well: "To either side a blur of abstracted London texture, as free of meaning as sampled skins in a graphics program." Gibson works the human/machine imagery with customary brio. Milgrim "sympathises" with his phone's "kernel panic" - an evocative name for crashing - in stressful situations. Bigend speaks of Milgrim's recovery in cybernetic terms: "There's always more of him arriving, coming online." It's also rather wonderful that any writer can have a character "draped, clearly terrified, back in the lift grotto, next to the vitrine housing Inchmale's magic ferret" in a commercial novel. Gibson has an eye for detail and a poet's ear for unusual phrases, modern and archaic: slut's wool, herf gun, paradoxical antagonist.

This may sound like an alienating terrain but Gibson has always written with an empathetic imagination. Take Meredith, a fashion buyer who passionately recalls the line of shoes she designed, currently entombed in an unreachable warehouse due to the label going bankrupt. She's primarily there to provide an inside edge on the fashion industry ("Everyone was waiting for their cheque. The whole industry wobbles along, really, like a shopping cart with a missing wheel") and a potential lead on the Gabriel Hounds designer. Yet her story exemplifies Gibson's genuine curiosity and interest in human experience - he's done his research and relays his affection for his numerous subjects with infectious enthusiasm. Alas, by the time Hollis's ex-boyfriend shows up - a base-jumping conceptual artist bankrolled by a shady millionaire "motivated by a sense of Swiftian rage" - this enthusiasm is harder to share.

And that's the crux of all that's right and wrong with the novel: Gibson clearly loves all this stuff. A zealous fervour for Festo's penguin-shaped dirigibles (which you can look up on YouTube), the hyper-intellectualisation of trouser design or the latest killer app pervades the pages like a watermark. By the time the thriller plot makes good on its promise and the threats become palpable, a high-tech counterattack has already been in progress for several chapters. If it's what got us into this mess, it's also going to save the day. There are some mild twists and reveals up to the last page, but the ending is as relentlessly cheerful as that of a comic opera: everyone "comes through", revealing their physical and mental potential in a climactic set-piece; the medication was a placebo all along, the bad guys are exiled, the good pair off and marry. Much ado about denim.

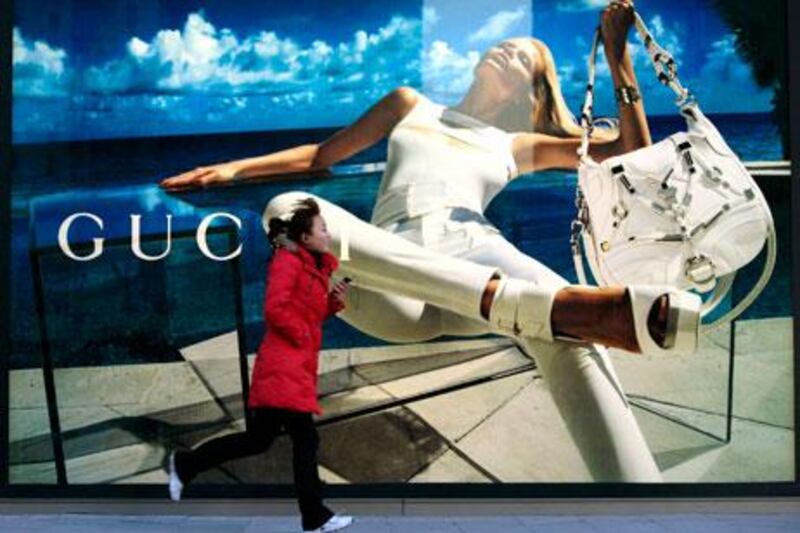

It's a striking move in the dourly circumspect genre of speculative fiction to have all the corporate espionage, surveillance paranoia and escapist psychosis finally undercut by romantic love. Perhaps Gibson simply means to reproduce the commercial logic that he's spent the novel satirising. Yet his cyberpunk aesthetic is beginning to feel distinctly less nihilistic and more hopeful. In 1993's Virtual Light, he gave us a gritty dystopia set in the near future where the middle class has died out altogether, leaving a society of super-rich corporations and the beleaguered working-class majority. In Zero History the middle classes are the artists, the musicians and designers, finding their power in the ready availability of technology. It's our world, in a sense, but it seems lighter and more virtual than science-fiction. By its end, the novel resembles nothing so much as a piece of well-designed, feel-good advertising.

Luke Kennard's third poetry collection, The Migraine Hotel, is published by Salt.