Exit the Colonel: The Hidden History of the Libyan Revolution

Ethan Chorin

Public Affairs

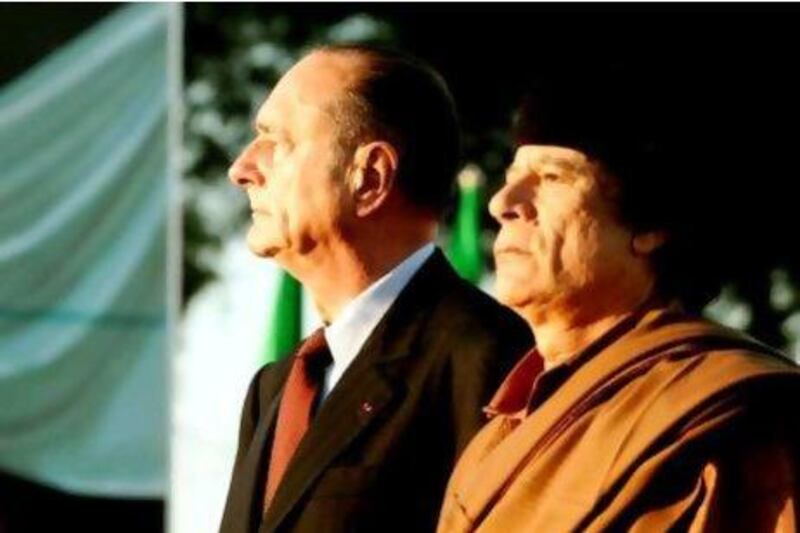

In the United States and Europe in the early 2000s, the name Muammar Qaddafi typically summoned up snorts of derision and mental images of Libya's "buffoon" dictator, given his predilection for wild hairdos and wacky outfits.

But fashion statements were only the start: Qaddafi would show up at official events flanked by Amazonian female bodyguards; sought New York City officials' permission to pitch his tent in Central Park (denied); implored Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian prime minister, to hire him 200 models, to be paid £53 (Dh312) to listen to his lecture on Muslim women, then join him in drinking warm camel's milk under the stars.

Qaddafi was also the self-appointed "king of kings of Africa", less flatteringly dubbed the "mad dog of the Middle East" (Ronald Reagan) and "the wild man" of the region (Anwar Sadat). So it's probably not surprising that a week after the colonel's violent end on October 20, 2011, by a rebel mob, he was not so much mourned as parodied: on the popular US television programme Saturday Night Live,"Ghost Qaddafi" reported from "hell" that he'd learnt: "First, never dare people to kill you." Second: "Never refer to your people as 'rats'."

Qaddafi did both and much worse during his 42-year reign. In his final years, he found support from western nations that sought oil and weapons contracts. But, less obviously, they were also eager to use Libya as a political showpiece.

So enamoured were the world's powers of these advantages of the western-Libyan alliance that they apparently could brush aside such Qaddafi horrors as the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in December 1988; the bombing, of France's UTA Flight 772 over Niger in September 1989; and the torture and imprisonment of untold thousands in Libya's prisons (unless they were student protesters in Benghazi and Tripoli, in which case they were unceremoniously strung up in public and left to die).

While these events brought international sanctions against Qaddafi's government in 1992, those measures were lifted in 2004. The colonel's western allies then tried mightily to get back to normal; all that oil awaited them. Yet once the revolution against Qaddafi began in earnest in early 2011, the West changed course and aligned against him as one. What caused such radical policy changes in the region? This is the intriguing question the Middle East scholar Ethan Chorin tackles in his detail-rich book Exit the Colonel: The Hidden History of the Libyan Revolution.

"Much of what happened to Libya is the result of negligence - negligence on the part of Libya's leadership and the international community, particularly the United States and Europe, which paid attention to what was happening in the country only when it was politically or economically expedient," writes Chorin, one of the first American diplomats posted to Tripoli following the lifting of sanctions.

In Libya, Chorin worked as a US economic and commercial attaché until 2006, later serving as a diplomat in the UAE. Today, he still works on Libyan issues as a business developer for a company in Dubai and as cofounder of an NGO constructing a trauma centre in Benghazi. So he has the cultural and historic background to weigh in on just what happened between the West and a nation that once seemed so irrelevant to world affairs.

In his book, which starts out ponderously slow but picks up at the point of the revolution and the colonel's exit, the author assesses just why Libya under Qaddafi's rule was relevant to the world: oil of course was a factor (Libya's reserves rank it first in Africa, ninth worldwide); another was Qaddafi's fabulous wealth and the power it gave him, alarmingly for the West, to prop up terrorist groups and revolutionary movements around Africa and the Middle East.

Chorin's third reason for Libya's "relevance", however, is his most intriguing. "Libya became the field on which the West was able to take a decisive public stand in support of the Arab Spring," he writes, noting how this "decisive" stand occurred amid an internal US government conflict pitting Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (pro-intervention) against (anti-) Secretary of Defence Robert Gates and set the stage for a key policy speech President Barack Obama delivered on March 28, 2011, explaining US action in Libya.

The author walks us through the history to that point: how, in 1969, Qaddafi, a semi-educated junior military officer, staged a bloodless coup against Libya's King Idris. How, in the 1970s, the colonel bought time for the ad hoc solutions he implemented to confront Libya's problems, most of which failed; how he also worked to "sow confusion" to keep associates and other countries guessing about his motives. Qaddafi also raised concerns about sociopathic tendencies with his brutal put-downs of perceived slights, his acts of stagecraft (allowing goats to wander through high-level meetings), three-hour speeches, and announcements that "feeble-minded individuals must be weeded out" and "a cultural revolution must be staged" to rid Libya of "poisonous" ideas.

In those first years he spent generously on health and education but also purged virtually all of his former fellow revolutionaries. By 1975, the "gloves [really] came off", Chorin says, of those student hangings and "revolutionary committees" which spied on everyone. Worse: Qaddafi tried to take over neighbouring Chad and became pals with Ugandan strongman Idi Amin. His list of outrages was long, causing the US to cut ties with him in 1981. Then came Lockerbie, resulting in the imposition of UN sanctions in 1992 (lifted in 1999).

US diplomatic ties remained severed. But as the threat from Al Qaeda deepened, and despite (as one Clinton administration official put it) "a healthy scepticism that Qaddafi could be reformed", US policy, in 1998, shifted. Libya, after all, might prove helpful on the terror front; its Islamic Fighting Group, which Qaddafi despised, had links to Al Qaeda and the embassy bombings of that time.

Qaddafi signed up wholeheartedly for rapprochement: he paid at least US$1.5 billion (Dh5.51bn) in claims to the Lockerbie and UTA families and agreed to discontinue his WMD programme. Accordingly, the US got friendlier; oil companies rejoiced; the kickbacks machinery fired up again. And the author and other diplomats revived the US presence in Tripoli, where they were housed in a hotel built over a Jewish cemetery (while the local officers club was adjacent to a foul sewer pipe) - Qaddafi-style reminders of who had the power.

The honeymoon soon ended, Chorin writes, but there were interesting highlights along the way: one was Qaddafi's son, Saif Al Islam who, unlike his seven siblings, seemed bent on reform. Standing in for his father, he invited to Libya advisers with western training in the sciences and administration, to convince the West that reform was really happening. At the same time, Saif bolstered his own credentials, pursuing a doctorate at the London School of Economics, which prompted an investigation about the British government's influence in his schooling, the huge sums of money he forked over and the academic tests he may not have taken himself.

Other highlights include Qaddafi's relationship with Berlusconi and Tony Blair, the British prime minister - where again, magnificent sums of money greased the skids (Italy paid "reparations" for its long-time control of Libya in exchange for construction contracts; Blair pursued contracts for British business. Another Chorin topic of note: the "ghost flight" renditions of terrorism suspects from Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo to Libya for interrogation (always with "assurances" that their human rights would be respected).

Libya's human rights record, of course, was abysmal. Beyond the ghost flights and student hangings were events like the government's massacre of 1,200 political prisoners at the Abu Selim prison in 1996 and its bizarre 1999 charges that five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor in a Benghazi hospital had deliberately infected 453 Libyan children with HIV (the European Union saved them from execution).

Here also is where the book gets really interesting, as Chorin details the conflict in Washington once the Arab Spring sparked Libya's rebel movement in 2011, along with Qaddafi's vicious response. Should the US intervene by enforcing a no-fly zone? High profile "humanitarian hawks" - most of them women - lobbied to impose a new doctrine called Responsibility to Protect (R2P), whereby the international community is held responsible for protecting citizens against their own countries' genocidal policies.

R2P won out, and "Clinton and Obama appeared, to their credit", Chorin writes, "to be looking at Libya as a key piece in convincing the 'Arab Street' that the US interests and commitments, while rooted in security and economics, had a moral dimension …". In fact, Obama recognised that US credibility itself was at stake. On March 28, 2011, he outright endorsed the Arab Spring, stating that "wherever people long to be free, they will find a friend in the United States".

In short, Libya provided the perfect stage (as Syria never could) for this policy stance.

Still, the warm and fuzzy feelings this move engendered had an underside of failure, Chorin argues: this was the massive amount of weaponry Qaddafi acquired as a direct result of the 2003 rapprochement - and used against his own people. Why did the West risk these weapons seeping out into the hands of extremists, the author ponders.

"In the final calculation," he writes, US and key members of the EU and Arab League intervened in Libya not for oil, not for humanitarian reasons, though these were important, but because Libya was "one of the few Arab Spring countries in which the US had freedom to act without upending long-standing and economically and politically valuable relationships".

Libya's "irrelevance" thus became an impetus for action, Chorin says. Western leaders won by not appearing impotent in front of the "Arab Street". But that win had a steep price: an estimated 25,000-50,000 Libyans perished in the process.

And that terrible loss led right to the next big question: how does the Libyan model of western intervention pertain to Syria?

Joan Oleck is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York.