Beginning a book on Lebanese cinema with the question of whether or not Lebanese cinema exists at all might seem like a risky rhetorical move. If the author expresses doubts about the topic on page one, who's to say that readers will bother turning to page two? But the film scholar Lina Khatib, in her new book Lebanese Cinema: Imagining the Civil War and Beyond, clearly believes in her subject, and by the end of her 200-page study, readers will too.

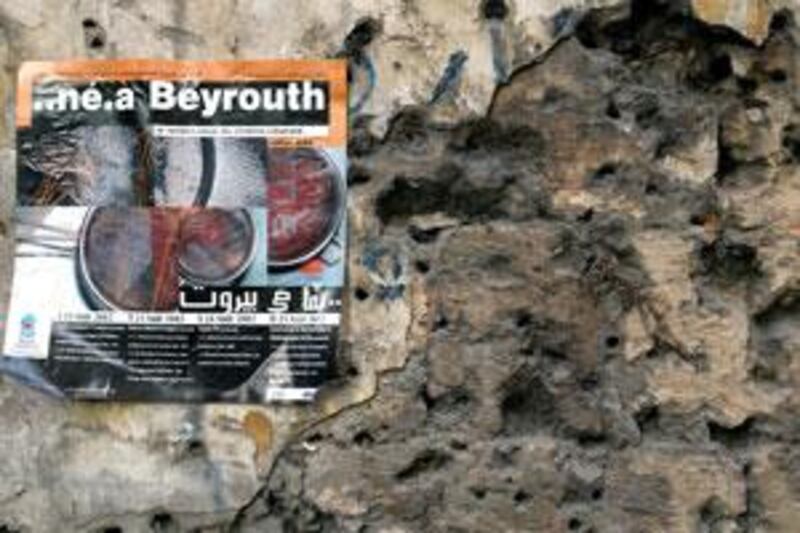

"Though it still has a long way to go, Lebanese cinema is heading towards maturity," says Khatib. "It is starting to gain momentum and this is something to be proud of. Lebanese cinema is starting to have a real presence on the international film scene. And credit is due to the filmmakers themselves. They are planting the seeds of what will become a cinema industry in the future." Published by IB Tauris in London as part of its World Cinema Series and celebrated with a launch party in Beirut during the Né à Beyrouth Festival of Lebanese Film, Lebanese Cinema is the first serious, analytical account of feature-length film production in Lebanon from the 1980s through to the present. It also joins an increasingly longer list of new books that document and discuss national cinemas in the region, such as Viola Shafik's Popular Egyptian Cinema: Gender, Class, and Nation, Hamid Dabashi's Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema and Insights Into Syrian Cinema, edited by Rasha Salti, all of which suggests that Arab cinema is experiencing a renaissance.

"Publishing on cinema also has a snowball-effect mechanism, if I can put it like that," says Khatib. "It takes a couple of books to convince publishers that there are readers out there for more books on film. It has happened at the same time as various Arab cinemas have reached international attention. It's a very positive sign that these books are appearing," she says. "But we need more." In decades past, Egyptian cinema was considered the region's lingua franca in terms of cultural production. Egyptian movies from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s were musical and melodramatic, and through television they made their way into living rooms from Morocco to Iraq. Egypt still churns out more feature films a year than any other Arab state. But Hollywood blockbusters tend to dominate the multiplexes in the Middle East. As a kid, Khatib remembers that "cinema for me meant either Hollywood or Egyptian cinema". Between the two powerhouses, Lebanese cinema never had much of a chance. During the 1975-1990 civil war, scores of ornate movie theatres in the capital of Beirut closed down due to the fighting. The few that remained open screened martial arts films for audiences of militiamen. The rare Lebanese feature simply ripped off the formulas of Hollywood action movies.

But what Khatib discovered while researching and writing her book is an alternative history of Lebanese art house films, "a quiet cinema", she calls it, that went largely unseen during the war but has become more and more visible over the past 10 years, thanks to the screening of Lebanese films in festivals from Cannes and Locarno to Abu Dhabi and Dubai. (Many of the newer films in Khatib's book have been released in theatres in the UAE. A few of the older films were showcased at the Third Line in September last year, as part of the programming organised for the Dubai gallery's exhibition Roads Were Open, Roads Were Closed.)

When Khatib says that Lebanese cinema does not exist, what she means is that it does not function as a robust, full-fledged industry. But it does exist, she argues, as an accumulation of independent films by imaginative directors who work by sheer will. It has achieved critical mass in terms of creativity. (Though this subject lies outside of the scope of her study, in conversation Khatib lays out a compelling argument for how the institutions and infrastructures for film production that are being put into place in cities such as Abu Dhabi and Dubai could be complemented by the raw talent brimming in Beirut - a model for regional collaboration, she says, that could benefit Arab cinema as a whole.)

In her book, Khatib arranges more than 30 films into a story about how the style and substance of Lebanese cinema has developed. While the films are certainly as diverse as the Lebanese population, they are more heavily indebted to avant-garde French cinema than to mainstream American movies or Egyptian song-and-dance numbers. They are also all, in one way or another, films about the civil war, its causes and its consequences. Ziad Doueiri's West Beyrouth and Danielle Arbid's In the Battlefields, for example, depict the lives of adolescents on opposite sides of the Lebanese capital's Green Line, a subtle argument that life goes on during times of war. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige's Around the Pink House and A Perfect Day delve into the politics of the postwar era and the question of whether the war should be remembered or forgotten. The films of Ghassan Salhab portray Beirut as a city constantly on the verge of devouring itself, illustrating the extent to which the problems that fuelled the civil war are unresolved and threaten to flare up again. Lebanese cinema grapples with the trauma of the war years, but it also recalibrates the booming violence of the conflict to allow for more intimate stories of love, trust and betrayal.

Lebanese Cinema, Khatib's second book after Filming the Modern Middle East: Politics in the Cinemas of Hollywood and the Arab World, attempts to explain why the civil war looms so large in contemporary Lebanese films despite the fact that the conflict ended nearly 20 years ago. Through a close critical reading of the films, Khatib argues that while some may regard cinema as a projection of national identity, whether real or imagined, Lebanese films are perhaps exceptional in that they reject the notion of there being any such thing as national identity to begin with.

Lebanon's national identity remains contested and unfixed, and so its cinema tarries with the destruction of the state and the disintegration of society. Khatib also suggests a therapeutic element to the cinematic obsession with the civil war. Films about the conflict - such as Josef Fares' Zozo, in which a young boy witnesses the shocking wartime death of his family, then recovers his childhood innocence in exile in Sweden - may be a way of putting the past to rest. But the violence that ruptures into films such as Michel Kammoun's Falafel - about a night in the life of an affable young man named Toufic - suggests that films about the war are not necessarily representing memories of a past war but fears of a future war.

Some of the films that Khatib studies are recent and well known. But other films are older, more rarely shown or in some cases almost impossible to find, such as Maroun Baghdadi's Beirut Ya Beirut and Little Wars, Borhane Alaoui's Letter from a Time of Exile and Roger Assaf's Ma'raka. So vivid are Khatib's descriptions and so dense are her passages attesting to each film's significance that one wishes copyright laws and licensing fees were such that Lebanese Cinema could come packaged with an accompanying DVD. Baghdadi's films, in particular, are considered the cornerstone of Lebanese cinema, but at this point, they are more often discussed than seen. Compounding the mystery is the fact that the filmmaker died in 1993 after plunging down an empty lift shaft in his apartment building. He was 43. Though he won the jury prize at Cannes in 1991 for his film Out of Life, his works have never been available on DVD and they have only rarely been screened for local film festival retrospectives. (Beirut Ya Beirut remains groundbreaking for its complex and nuanced portrayal of South Lebanon through the tangled relations of four characters: a bourgeois woman, her two boyfriends and a refugee who quits Beirut to join the resistance movement.)

One of the more rambunctious passages in Khatib's book describes her attempts to track down a copy of Baghdadi's Beirut Ya Beirut at Lebanon's National Cinema Center. Everyone from Baghdadi's widow to his former colleagues and contemporaries insists that the centre has the film. Khatib even finds a documentary that shows footage of a director placing the reels of Baghdadi's films on to a projector in the centre. But when she pays the centre a visit, staffers vociferously deny having any knowledge of the film's whereabouts.

In Lebanese Cinema, Khatib couches her arguments in a good deal of political context and historical perspective. She offers introductory chapters on Lebanese national identity and the relationship between state formation and cinematic output. She courses through a vibrant narrative account of feature-filmmaking in Lebanon, touching on persistent problems such as funding, government indifference, censorship and the often dramatic schism between a director's artistic ambitions and an audience's expectations of being entertained.

But what lends the book both charm and readability are Khatib's anecdotes and asides, such as her account of watching her parents prepare for the Beirut premiere of Mohammad Salman's Who Puts Out the Fire in 1982 (at the time, Khatib was too young to join them). Moreover, what lends Lebanese Cinema value is the constant credit Khatib gives to other writers, rare though they may be, who have put hours, days, years and decades into the often thankless task of recording the contours of Lebanon's film culture for posterity.

Still, as Khatib sees it, there is still much to be done: "When I was planning the book, I was struck that there's so little out there that gives concrete information on Lebanese cinema," she says. "I wanted the book to be useful. I had to have a brief history of Lebanese cinema, and to be honest, I could have written a whole book on just that. So that was my contribution to knowledge in the field. I wanted the academic reader, the Lebanese reader and the general reader to find something of use."

There is also still much to be done in Arabic as opposed to English: "There have not been many analytical books on cinema published in Arabic. There have been some excellent books, such as Mohamed Soueid's Postponed Cinema in 1985. But that was 1985. I hope publishers will take on more book projects. And I hope that these books will be translated into Arabic, too. When it comes to publishing and specifically academic publishing more can be done. Publishers really think that there is no readership. It's not true. There are readers."

If there are readers for the books, then it stands to reason that there are viewers for the films. In this regard, Khatib is planting the seeds of a future industry alongside the directors she so clearly admires. All that is needed now is for private sector financiers and public sector bureaucrats to believe in Lebanese cinema as much as she does.