A new biography of the controversial philosopher fails to capture what remains most vital about his work, Sam Munson writes: the style and energy of its opposition to modern liberal pieties.

Searching for Cioran

Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston

Indiana University Press

Dh112

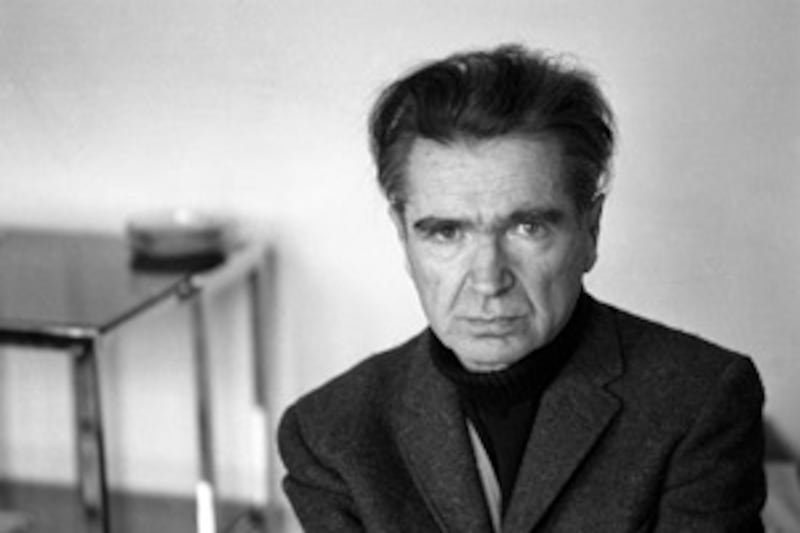

The Romanian philosopher EM Cioran remains one of the most difficult modern writers to come to terms with. With an aphoristic, charged, almost violent style, and a portfolio of subjects well outside our contemporary philosophical mainstream - despair, ecstasy, boredom, insanity, suicide, crime, illness, nothingness, music, sex, entropy, all considered as raw and immediate experiences, not as matters for academic investigation - he can seem like an atavist, a soul in permanent unarmed combat with the mores of enlightened society. "Annihilating," he wrote in The Trouble with Being Born, "flatters something obscure, something original in us. It is not by erecting but by pulverising that we may divine the secret satisfactions of a god. Whence the lure of destruction and the illusions it provokes among the frenzied of any era."

Sentiments of this kind - admiring aperçus on destabilisation and destruction - are looked at askance these days, no matter how felicitous their expression. But the temptation to write about the mind that produced them is as strong as the difficulties surrounding such a task are thorny and serious. Cioran's idiosyncratic and allusive style and the lack of obvious socio-historical references in most of his books present a formidable challenge to any scholar. The careful control he exerted over his own biography - re-shading facts here, altering emphasis there, rebuking his younger self while still espousing the principles of his youth, above all retaining an exquisite consciousness of himself as a potential biographical subject - renders him at least partially resistant to the scrutiny of a conventional researcher.

In writing Searching for Cioran, the Romanian émigré Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston (until her death in 2005 a professor of comparative literature at Indiana University) had quite an exegetical task before her. And the appearance of her book, despite its dubious success at this double task, is sure to excite any reader alive to the power of the 20th century's counter-Enlightenment thought. Born in 1911 at the Transylvanian border into a well-respected Romanian family, Emilian Cioran was the second son of a vigorous and intellectual Orthodox priest. Both sides of his family participated - from the safety of bourgeois prosperity - in the forward-looking political movements aimed at bettering Romania's condition. He would later call his childhood in the foothills of the Carpathians "crowned", a high encomium from a man who would in his later years offer up, as a curt principle by which to accomplish the task of living: "To have committed every crime but that of being a father."

Cioran, though an unremarkable student, showed his inclinations toward the ineffable early, suffering from chronic insomnia and walking through the streets of his hometown for nights on end, throwing himself down on the sitting room couch in fits of physical despair. He admired Nietzsche, the French symbolists, and other artists of the extreme, an admiration he carried with him into the years of his late adolescence and young manhood. Unlike most other adolescent devotees of Romantic nihilism, however, Cioran had both the energy and talent to draw the beginnings of a philosophy out of his obsessions. In 1934, when he was scarcely 23 years old, he published an investigation of the angst of existence and the burden of history called On the Heights of Despair, a book that bears strong resemblances to both Also Sprach Zarathustra and Baudelaire's Le Spleen de Paris. On the Heights comprises a series of brief meditations on various unsettled human conditions, including a state Cioran referred to as "being lyrical", an explosion of inner protest against modern Europe's "culture of sclerotic forms", with a necessary "grain of interior madness" - a willed and illuminated barbarism. His idiosyncrasy verges on the solipsistic, as this passage from On the Heights of Despair indicates:

"True solitude is the feeling of being absolutely isolated between the earth and the sky... [A] fearfully lucid intuition will reveal the entire drama of man's finite nature facing the infinite nothingness of the world." To call the man a nihilist is something of an understatement. He outdoes even Herodotus - who instructs us in the Histories to call no man happy until he is dead - in his proclamations of the punitive (or criminal) nature of our existences. Later in his career, he would identify birth itself as the primary human tragedy: "We have lost, being born, as much as we shall lose, dying. Everything."

It cannot be altogether surprising that the author of the above lines was attracted for most of his life, in one form and another, to the great derangements of European political vitalism, particularly the desire to reinvigorate national consciousness and institute a new, illiberal and aesthetically splendid order. The philosopher-poet of On the Heights of Despair was, along with a number of his intellectual contemporaries, including the historian of religion Mircea Eliade and the journalist and philosopher Petre Tutea, also a nationalist seeking transcendent glory for his homeland.

His third book, Romania's Transfiguration, appeared in 1936, and praised Romania's fascist cadre, the Iron Guard, and the transformative power of political violence. Cioran would leave Romania the following year for France, without ever becoming an official part of the Right's government, as his friend Tutea did. His youthful outburst of Fascist sympathy remained his most explicit political utterance. And he later repudiated - or partially repudiated, for the terms of his rejection are aesthetic and obscure - Romania's Transfiguration, going so far as to censor its objectionable parts in its second edition and to tear the offending pages out of his own copy.

But his interest in the extreme never diminished, becoming as important to his later development as the encounters with existentialist thought that shaped his thirties. During his long years as a doctoral student in Paris (a vocation he pursued because it guaranteed him cheap housing and discounted meals in student-only restaurant) Cioran betook himself to the cafe that served as the centre of operations for the existentialists, whom he apprenticed himself to without their consent. (They called him "the clerk," according to Zarifopol-Johnston, because of his studious attendance at their sessions.) While he found in the thought of postwar France great resonances with his own sense of exhaustion and futility, and even abandoned Romanian for French in writing and speaking, he avoided the commitment to meliorist politics that characterised much of postwar European intellectual life.

His mature career he gave over to pondering the genus of problem approachable only through a bitter, compressed mode of aphorism, which he modelled consciously on the French dramatist and epigrammist Nicolas Chamfort - a mode that extends to the very titles, sly and confrontational, of his books: A Brief History of Decay, The Temptation to Exist, The Trouble with Being Born. Cioran lived in Paris and worked steadily in this late style until a few years before his death in 1995, avoiding sociopolitical entanglements, weathering a storm of controversy over Romania's Transfiguration, and serving as one of the last practitioners of a now-unfashionable form of metaphysical inquiry - and one of western philosophy's last great stylists.

Given his fundamentally anti-philosophical positioning, and his hard, ironic voice, as well as his unorthodox political views, Cioran has come in for a great deal of comparison to Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, a latter-day representative of corrosive, fearless scepticism. It's hard to dispute such claims, but they have the sad effect of dating Cioran. In philosophy, the sceptical nihilists have lost. This is to say nothing of that fact that his concern with artful writing by itself places him well outside the scope of our professional philosophers, or that right-thinkers consider Cioran anathema for the fascistic undercurrents in his thought (although this seems both intellectually useless and hypocritical in light of the large number of Stalinists who have managed to pass unhindered into the European canon). Thus it is that Cioran has come to be seen as a kind of curio, the possessor of a masterful and pleasurable prose style, yes, but a figure with little else to offer our sane, humane, justice-seeking, transactionally-minded modern world.

One would imagine the task of any "critical portrait" of Cioran would be to assess the truth of this schema, to probe into the man's work for signs of life. Sadly, Searching for Cioran is very nearly a complete failure at this, despite Zarifopol-Johnston's curriculum vitae being ideally suited to the task. A translator of two of Cioran's major works - On the Heights of Despair and his anti-hagiography Saints and Tears - her knowledge of her own country's cultural past cannot be faulted, nor can the tour d'horizon she gives of the postwar Parisian intellectual scene. Her basic contentions about Cioran's thought seem so sound as to be nearly self-evident. Why, then, does Searching for Cioran feel so inadequate as both critical study and biographical investigation? Is it the wooden infelicities that plague her prose, such as this:

"So what, then, is Cioran doing in Romania's Transfiguration? One the one hand, his discourse is clearly part of a general public discourse dictated by the specific historical moment. On the other hand, it is so unlike anything else being written on its subject that it stands out in the political contest as a sort of aberration. What makes it so is that fact that he uses to the utmost the resources of the genres within which he is operating... while at the same time undermining them with his scepticism and lack of faith."

Or is it the terminally cautious nature of her conclusions: that Cioran's case sheds light on uneasy fascination modern philosophers have with political power, that he deserves a place among the major thinkers of the 20th century, and that his youthful support of the Romanian fascists belongs as authentically to his philosophical temperament and vision as any of his later propositions. Of all the possible styles through which to approach Cioran, this is the most valueless. A philosopher with so abiding an interest in the aesthetic quality of his prose, and in the extreme realms of human life in general, is ill-served by writing so lifeless, and insights so bound by the very traditions Cioran spent so much of his energy violating, with wit, grace, and irony. (To be fair, Zarifopol-Johnston's book remained incomplete at the time of her death. But what we do have gives no indication that additional material would be more acute.)

And yet we have in this clash of aims, this failure of critical and biographical sympathies, the answer to the question Zarifopol-Johnston fails to ask: what does Cioran offer us? An alternative, I would argue, to the shuffling and reshuffling of pieties, to the superficial investigations of language and politics, to the long academic boredom that has settled over philosophy. To read Cioran is to be reminded of another strain in Western culture, one that rejects the progressive ethic of political compromise and social improvement. It is customary, now, to refer to such eruptive and wild-hearted modes of thought, particularly where they coexist with a penetrating intellect, acute criticisms of the liberal political order, and high talent for prose, as "dangerous" - to demean with this label anything touched by the slightest breath of anti-modern sentiment. Cioran's work belongs to the category of the "dangerous". And the word applies as both a term of opprobrium and a term of the very highest praise: After all, if philosophy is not dangerous, what purpose can it have?

If we take nothing else from the work of Cioran, let it be that question - asked without fear.

Sam Munson has written about books for The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times Book Review, and other publications. His first novel, The November Criminals, will be appearing next spring from Doubleday.