Is the world's most popular unfunny comic strip better without its titular fat cat? AS Hamrah investigates.

Garfield Minus Garfield

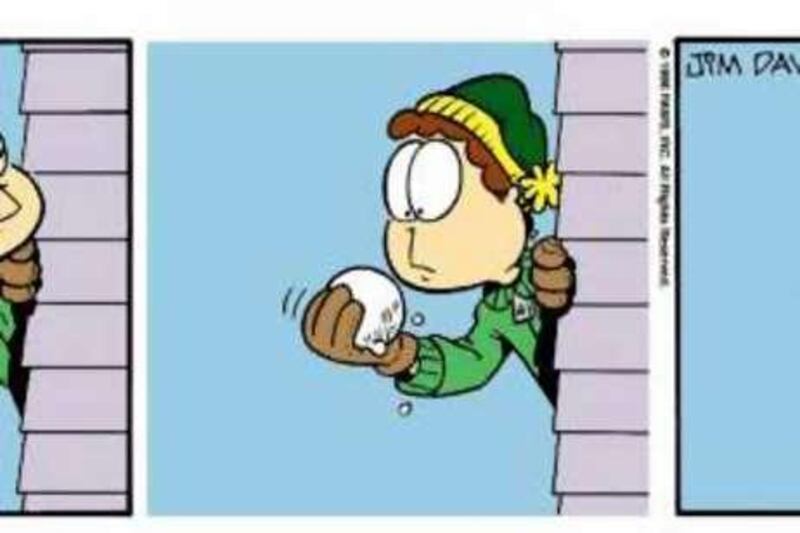

Jim Davis

Ballantine Books

Dh45

A friend from Canada called me the other night and told me about her new roommate, a young woman who had arrived with a box of memorabilia dedicated to the comic-strip cat Garfield. The morning after this new roommate moved in, my friend woke up to find Garfield items deposited around the apartment - a stack of Garfield paperbacks piled on a shelf in the bathroom, a Garfield Chia Pet plunked down on the kitchen counter. Various nooks and crannies, formerly empty of orange cartoon mascots, now held grinning Garfield tchotchkes. The place had been livened up by merchandising.

Does everything happen twice? The most insignificant details of our lives can come back to haunt us. Years ago when I was living in Boston, the girl I was dating moved up from New York. A sure sign of love, giving up New York for Boston. She'd found an apartment by answering an ad in a newspaper, then moved into it sight unseen. When she got there she found out her new roommate, also a girl in her early twenties, had decorated the entire place in Garfieldiana. Tissue box covers, cookie jars, coffee mugs, sheets and pillowcases - everything had Garfield on it, even the light switch panels.

My girlfriend didn't want to make waves by criticising her new roommate's choices in home decor. She couldn't bring herself to say anything beyond, "So, you really like Garfield, huh?" "Oh yeah!" the roommate enthused, "I really do." For a couple of months she tried to tough it out in this Garfield-heavy environment, which Garfield dominated even with the lights out. At night when she closed her eyes, the orange face of Garfield floated in the black behind her eyelids. Eventually she gave me an ultimatum. She could no longer live like this, oppressed by depictions of a lasagne-eating cat. She had to get out. Either she moved in with me or she was going back to New York. We compromised by moving to New Orleans together. You could say Garfield drove us there.

From Canada to New Orleans, Garfield inhabits the North American consciousness in hidden ways too small to think about. We tend not to notice the ubiquitous; we don't have time to contemplate the unimportant. When the ubiquitous and the unimportant are not very entertaining, they barely register at all. But they're there. For Jim Davis, Garfield's Indiana-based creator, who oversees a vast merchandising empire called Paws, Inc., this is a good thing. In a new career-retrospective collection called Garfield: 30 Years of Laughs & Lasagna, Davis says he's flattered by people who buy licensed Garfield merchandise. "I think it's neat if someone can relate to the character enough to want to demonstrate that by owning something 'Garfield,'" he writes.

As we've seen, it isn't always so neat for other people. Today the Garfields buried in the culture's collective unconscious bubble up in strange combinations of the hostile and cheerful. The most well-known of these, Garfield Minus Garfield, a dot-net that became an internet meme, now has its own book, which Ballantine is releasing concurrently with its official Garfield collection. Garfield Minus Garfield, as the title implies, dispenses with Garfield completely, erasing the feline star from the comic strips to leave nothing but his hapless owner, Jon Arbuckle, talking to himself and confronting the existential void that is his life. Turning Garfield into an absent presence underscores the strip's sub-themes, the ones half a layer below the gluttony, laziness and cynicism that are Garfield's avowed characteristics. All the boredom, loneliness, failure, and isolation of Jon's life come out in bold relief when Garfield and his thought balloons are not there to provide sarcastic commentary. The state of having nothing to do becomes the strip's theme, the feeling that "life is passing you by" or that "this is all there is," as Jon says to no one in a couple of these modified strips.

"With Garfield there you've been distracted from the truth," writes Dan Walsh, the site's creator, in his introduction to the Garfield Minus Garfield book. Walsh, a bored Dubliner who began the site in early 2008, quickly found out people like the truth. Jon's uneventful and purposeless life became a big hit on the internet, getting, as Walsh breathlessly puts it, "half a million hits a day!" Jim Davis took notice and instead of filing a lawsuit, happily glommed onto the fad. "Strip away Garfield's superfluous comments, and you're left with the stark reality of Jon's bleak circumstances," Davis writes in Garfield Minus Garfield. Is this the first time the creator of a multimillion dollar comic-strip has described his main character as "superfluous"? It probably is, but the sanguine Davis doesn't care. Happy for another revenue stream, he contributes 24 of his own erased strips to the book, one of which features Jon writing a memoir: "I was born on a farm . . . and then I wrote about my boring, empty existence."

Davis has, in effect, taken over Garfield Minus Garfield, reclaiming it from Walsh as his own creation. "The internet sensation - now in book form!" it says on the cover above the book's title. Below is the familiar signature "By Jim Davis," then under that, in smaller type, "With a Foreword by Dan Walsh, creator of www.garfieldminusgarfield.net." Garfield Minus Garfield, the book, hits existential dread hard, maybe too hard. Never before have angst and ennui been sold with such sunny ballyhoo. Combining the triviality of Garfield with a stare into the void can get uncomfortable in unexpected ways. It makes a travesty of human loneliness in a glib and shallow way that doesn't quite mesh, but like Garfield in general it can home in on its target pretty closely. "Without a doubt," writes Walsh, "the most heartwarming fan mails I received were from people suffering from bipolar depression." He quotes one: "I think that [your strip] is very special and portrays suburban isolation due to bipolar/depression/mental illness so accurately that it's almost scary. I have been dealing with bipolar and depression for the past five years and am just coming out of a three-year period of Jon Arbuckle's frighteningly similar lonely and sad existence..."

Reading these emptied strips one after another, you start to feel the accumulated weight of every other Garfield ever published, every Garfield thing ever made, and then you realise: Garfield has escaped and I haven't. Garfield, the most widely syndicated comic strip in the world, appears in about 2500 newspapers in 111 countries. Davis and his publishers claim 230 million people read it every day. The Garfield brand encompasses books, TV shows, movies, a website and all sorts of licensed merchandise. You name it, you can get it with Garfield on it. Finding its first success in the very early 1980s, Garfield is the quintessential Reagan-era product: ubiquitous but not loved, it has no currency but is worth millions.

Is it strange that a comic property so valuable is widely held to be not funny? Unfunniness, in fact, has become Garfield's chief characteristic. Its ubiquity combines with this view of it to make Garfield the perfect blank slate for the culture to write on. Unlike Charles Schulz's beloved and soulful Peanuts, Garfield exists as pure product. No one, maybe not even Jim Davis, respects it enough to elevate it for cultural analysis, to save it for the future. There is no taboo against screwing Garfield.

Not only that, screwing Garfield seems like a waste of time, which tends to makes the various Photoshopped Garfields funnier in the way that only something not worth doing can. One, called Silent Garfield, preceded Garfield Minus Garfield by a couple of years. So did another one called Realfield. Silent Garfield removes all Garfield's thought balloons, exposing the common humanity of the pet owner: he talks to his cat, his cat doesn't answer. Realfield takes this a step further, replacing Davis's Garfield with an immobile rubber-stamp rendering of an orange cat. This cat doesn't respond to Jon in thought balloons or otherwise. Its immobility is a rebuke to anthropomorphised cats specifically and to the funny pages in general.

Walsh may or may not have been inspired by these semi-anonymous creations. In any case, his detourned Garfield is the first to land a book contract. At lasagnacat.com, a TV-commercial production company in Los Angeles makes the best use of Garfield on the internet, turning individual strips into snippets of live-action sitcom, performed by a guy in an orange cat suit and a guy in a Jon wig, complete with a canned laugh track - and then, in an inspired fit of banal elaboration, adding effects-heavy Garfield music videos.

For the cartoonist R Sikoryak, Garfield combines the primal and the banal. He sees the strip as the product of an age saturated with TV sitcoms. "A classic strip like Nancy was silent movies," says Sikoryak. "Garfield is closer to I Love Lucy. It's expressive and sloppy in a way Buster Keaton wasn't. Those big eyes appeal to children. So does the strip's concentration on basic needs like food, sleep, and getting things you want from a big human you have contempt for. The strip sticks in their subconscious as grown-ups."

Sikoryak, who is known in the cartooning world for his ability to draw in the style of artists of the past, has done two Garfields: in a strip called Garish Feline, which originally appeared in RAW, Sikoryak rendered Garfield as a series of black-and-white de Kooning sketches. In the epic Mephistofield, Sikoryak retold Marlowe's Doctor Faustus as a series of colour Garfields, with the cat as the devil and Jon as Faust. Those who have always wanted to see Garfield with horns or a bearded Jon burning in hell will not be disappointed. In Sikoryak's work Garfield becomes a pictographic language capable of delivering classic themes and ideas in a jarring yet breezy way.

As a child, Jacob Covey, art director at the comics publisher Fantagraphics, used Davis's strip to teach himself to draw. Now, he says, he has a love-hate relationship with it, exacerbated by Silent Garfield, which helped him "learn more about comics by exposing the way Jim Davis panders to his audience by overexplaining every gag." One thing Garfield Minus Garfield proved to Covey, however, was that Garfield really didn't need to be there. Covey also thinks Davis owes a lot to Walsh. "Who would be talking about Garfield right now if it wasn't for Dan Walsh?" he asks.

"A strip that's cynical and mean but doesn't relate to what's going on in the world has nothing to teach us," Covey concludes. For Tom Spurgeon, editor of The Comics Reporter, "in Garfield there is no world. It's an empty-stage set, like standup comedy. Davis stripped away anything extraneous. His strip has an Eighties quality: it was successful because it was successful. It wasn't successful because people loved it, people loved it because it was successful."

For his part, Davis seems aware of this. In Garfield: 30 Years of Laughs & Lasagna, the cartoonist calls his fat, lazy, cynical creation the "iconic 'spokescat' for the Eighties generation: the 'Me Generation.'" It's a sign of the times that Dan Walsh and others want to shut him up, erase him from the picture.

AS Hamrah has written for the Los Angeles Times and Newsday, and is the film critic for n+1.