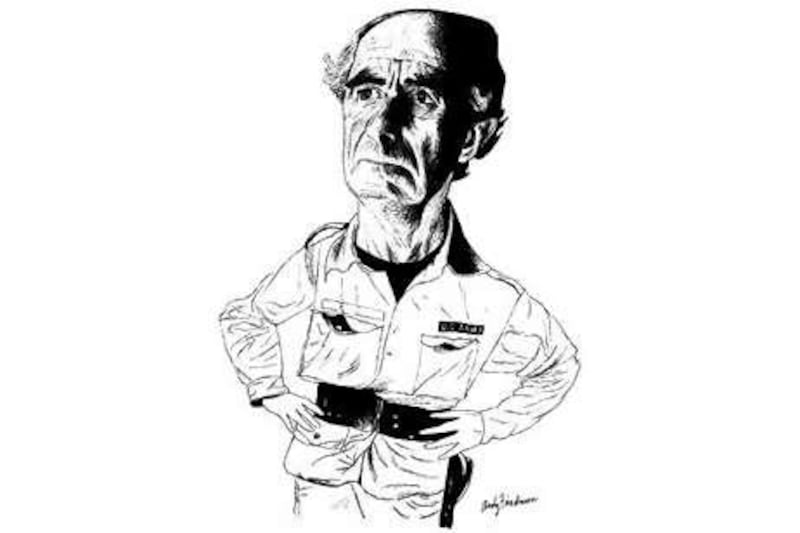

In the newest of what can now be called his late works, Philip Roth returns to the subject of mortality. But his hero is also a casualty in the opening battle of America's culture wars, writes Christian Lorentzen.

Indignation

Philip Roth

Jonathan Cape

Dh112

In 2005, the Library of America published the first of eight planned volumes collecting the works of Philip Roth, and announced plans to package his entire oeuvre before his 80th birthday in 2013. America's equivalent to the French Pléiade, the books confer canonical status in black jackets banded in red, white and blue. Only Saul Bellow and Eudora Welty were thus elevated while still living, and neither was publishing new work at the time - indeed, neither author was long for this world. In this sense, Roth could be said to have beaten his rivals into history: Norman Mailer, William Styron, Toni Morrison, John Updike and John Cheever all have yet to receive the Library of America imprimatur. But Roth is still writing prolifically, and his canonization could be mistaken for a premature burial.

As if to confirm this notion - or to mock it - he has written a string of novels told from literally or nearly beyond the grave. Roth has always displayed a preoccupation with the fragility of the human body and the tenuousness of our grip on life. Hospital set-pieces appear as frequently in his work as scenes around the family dinner table or in the bedroom. But during the past decade, Roth's writing has seemed to enter a late phase, with mortality itself the dominant theme. In three short novels - The Dying Animal (2001), Everyman (2006), and Exit Ghost (2007) - Roth has forged pressurised narratives about the indignities of growing old. David Kepesh, the narrator of The Dying Animal, confronts both his own decay and the cancer that has doomed a lover four decades his junior. "Think of old age this way," he advises, "it's just an everyday fact that one's life is at stake." Everyman begins at the funeral of its hero: "Old age", we are told, "isn't a battle; old age is a massacre." And Exit Ghost, grimly marketed as the last gasp of Roth's frequent alter-ego Nathan Zuckerman, doubled as an encomium to a fading literary era.

Yet Roth's characters have hardly been going gentle into that good night. Their rage takes the form of eros. Roth has cited Tolstoy's late novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich as a model for Everyman - and the connection suggests one source of inspiration for Roth's late style. But Tolstoy could never have imagined the possibilities for seduction in a retirement community. Even Zuckerman, impotent and incontinent after a prostate operation in Exit Ghost, labours over smutty fictional dialogues in which he flirts with a 30-year-old heiress. This summer The Dying Animal was adapted for the cinema as Elegy - a change in title that betrayed the filmmakers' anodyne approach to Roth's sophisticated perversity. A novel concerned with the "brutishness" of sex and death became a maudlin perfume advertisement on the big screen.

Indignation thus arrives as a corrective. Like its near predecessors, it is a short, visceral novel soaked in bodily fluids - mostly blood but also vomit and semen. Roth remains death-obsessed, but he has dispensed with cancer, dementia, erectile dysfunction and the other vicissitudes of senescence. Dying young is the predicament here. It is 1951, and for the youthful American male the prospect of being drafted into the Korean War is a ticket to annihilation. The narrator of Indignation is Marcus Messner, a 19-year-old sophomore at Winesburg College, in Ohio. Before making straight As and securing a future as a lawyer, Marcus is primarily concerned with avoiding the expulsion from college that would expose him to the draft. But as he reveals a quarter of the way into the book, he is already lost: "And even dead, as I am and have been for I don't know how long, I try to reconstruct the mores that reigned over that campus and to recapitulate the troubled efforts to elude those mores that resulted in my death at the age of 19."

We learn in the end that he dies in Korea, his genitals bayoneted "to bits". Killing the narrator off in advance loosens some of the strings that tie this novel together - and tightens others. Early on, Marcus's father, a kosher butcher in Newark, New Jersey, warns his son that "the tiniest misstep can have tragic consequences", an utterance that hovers over the narrative like a Chekhovian gun on the wall: the suspense centres on the question of which mistake will send Marcus to Korea - not whether he makes his grades, pledges the fraternity, or gets the girl. At its root, Indignation is about "the terrible, the incomprehensible way one's most banal, incidental, even comical choices achieve the most disproportionate results".

But there are matters at stake beyond the fate of one college student. Social forces are moving in colliding vectors in and around Marcus. Old ways are yielding to corporate capitalism, secularisation, the Cold War, meritocracy, and sexual liberation. The Messner butcher shop faces competition from a new supermarket in the neighbourhood, and the waning of the kosher tradition among Newark's Jews isn't helping. Winesburg College is engaged in a struggle to maintain and enforce its own long-held traditions and restrictions in the face of an ambitious student body ready to assume the license that would define postwar American youth. The threat of "godless Soviet Communism" looms in the minds of college administrators who would bolster sagging traditions with a new militarism.

The novel is set in motion by a fight between Marcus and his father, who, having lost two nephews in the Second World War, is "crazy with worry that his only child was as unprepared for the hazards of life." He fears that Marcus will die in a barroom brawl, and his paranoia drives his son out of the house - "I had to get away from him before I killed him" - from a local Newark college to Winesburg. Marcus chooses this school seemingly at random; Roth has something else in mind. There is a real town (though no actual college) by that name in Ohio, but Winesburg, Ohio is the title of a 1919 novel by Sherwood Anderson, a portrayal of Midwestern small-town life in a series of grotesques.

By sending Marcus to Winesburg, Roth is winking at the American literary establishment that preceded him. Anderson was a mentor to William Faulkner, and provincial liberal arts colleges, like the one in this novel, tenured the Southern and Midwestern writers variously known as the Fugitives, the Agrarians and the New Critics. The poet and critic John Crowe Ransom placed Ohio's Kenyon College at the centre of this movement, which was ascendant between the world wars. Though its aesthetics were Modernist, the school prized history and tradition - sometimes to the extent of romanticising the Confederacy. By the 1950s, these writers were being supplanted, in young magazines like Partisan Review and The Paris Review, by the New York Intellectuals, a group in which Roth stood out as the enfant terrible. Many of this school identified themselves as Jews - though few of them practised the religion - and their great theme was assimilation and the frictions it caused. They sought both to join the American mainstream and remake it in their own image.

Indignation is a novel of assimilation gone awry. Marcus grates against the company of his roommates and balks at the college's required chapel attendance. He declines the entreaties of the two fraternities on campus that accept Jews. Waiting tables at the local watering hole, he imagines that the customers - his WASP classmates - demean his attention by yelling "Hey Jew" instead of "Hey you" (Roth is borrowing this old saw from Woody Allen, among others). Called into the office of the genteel Dean Caudwell, who wants to help Marcus "adjust to Winesburg", he flaunts his adolescent atheism, quoting Bertrand Russell's Why I Am Not a Christian. In all this Marcus seems determined to enforce his own alienation, and at times he feels less fully human than his Newark-born cousins Neil Klugman (Goodbye, Columbus) and Alex Portnoy (Portnoy's Complaint).

If Marcus proves somewhat fixed as a character, so does Olivia Hutton, a brunette shiksa in his history class with whom he enjoys a brief, tortured affair. Their first date culminates with a sexual act in a parked car. When Marcus goes to the hospital for an appendectomy (an episode anticipated by several comic fits of vomiting), she visits him and repeats the favour. "That was not the way it went," a grateful Marcus worries, "between a conventionally brought-up boy and a well-bred girl." Olivia is a child of divorce with a history of heavy drinking. A scar on her wrist marks her as the survivor of a suicide attempt. She takes interest in Marcus's stories of the butcher shop but refuses to talk about her own family. By the time Marcus leaves the hospital and Olivia is summarily banished from campus by a nervous breakdown and a pregnancy (by another student), Olivia and Marcus represent strands in a social allegory that supersedes the novel's ramshackle plot. Roth conceives of the Fifties as a period of cruel transition for America: Olivia embodies a disintegrating WASP past, and Marcus a future of liberated ambition and narcissistic individualism.

The allegory comes chaotically to the fore during a blizzard that sets off the "the Great White Panty Raid of Winesburg College". As Marcus sits recovering from his operation, the boys on campus erupt into a pagan frenzy, ransacking the female dormitories. At the centre of it all they construct an effigy: "in the quadrangle yard, a large breasted snowman had been built and bedecked in lingerie, a tampon planted jauntily in her lipsticked mouth like a white cigar, and finished off with a beautiful Easter bonnet arrest atop a hairdo contrived from a handful of damp dollar bills." In the wake of the riot, the males of Winesburg are rebuked by the college president, Albin Lentz, a former undersecretary in the War Department, who calls them "an army of hoodlums imagining, apparently, that they were emancipating themselves." In harsh terms, he also reminds them of the gore awaiting them in Korea and the Soviet Union's recent testing of its own atomic bombs.

What to make of all this? Marcus himself is a study in restrained outrage; and in the end he is expelled for skipping, then refusing to attend chapel. A "Historical Note" at the novel's end relates that the chapel requirement would be eliminated after organised protests in 1969. These bring to an end of the constrictive traditions of Winesburg's old guard. But in addition to the principled activism of the Sixties, for which Marcus in his righteous indignation stands as a precursor, we see two new forces at work here: the frenzied licentiousness of the panty raiders and the strident militarism of President Lentz.

Roth's last work set in the past, The Plot Against America (2004), was widely read by critics as, in part, an indictment of the Bush administration. Indignation is a study of the origins of America's still flaring culture wars. When corporate capitalism crushes the dignity of a hard-working man like Marcus's father, and a social revolution strips away genteel tradition, only idealism remains to check permissiveness and aggression. And if that idealism should fade away, what's left is barbarism - literally "an army of hoodlums". Think of the vulgar pageantry and mild sadism of the coarsest American pop culture, from reality television to the films of Jerry Bruckheimer. Then recall that tawdry snow woman, tampon in mouth, and consider what happens when such an "army of hoodlums" is unleashed on a real battlefield. What you get are indignities. Every war has its atrocities, but the Iraq War has had to it an aspect of the American grotesque. To look at the photographs from Abu Ghraib prison, it's not hard to see the roots of those indignities in Winesburg, Ohio.

Christian Lorentzen is a senior editor at Harper's Magazine.