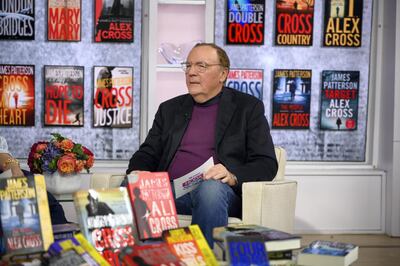

There are a good many unavoidably odd things about The House of Kennedy, the new book by James Patterson (with Cynthia Fagen).

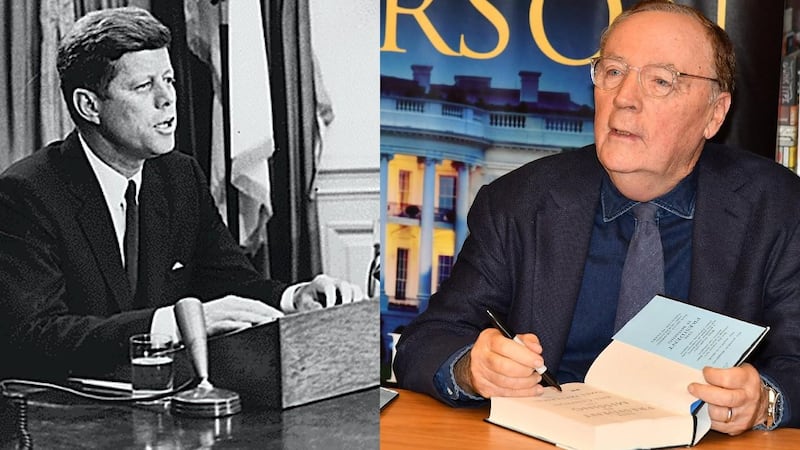

The first is the presence of Patterson himself: he's written or co-written well over 200 books, but only a tiny handful of those have been nonfiction, and only one of those, 2009's The Murder of King Tut (co-written with Martin Dugard), was presented as a work of straightforward history.

Patterson is one of the most prolific and bestselling thriller-writers in the world; finding him writing a history of four generations of the Kennedy family is like finding an 800-page history of the Habsburg Monarchy written by JK Rowling.

The book contains no foreword explaining why a mainstay of the fiction bestseller lists would turn to writing history. Perhaps the answer is purely personal; Patterson was a teenager when President John F Kennedy was assassinated in November of 1963, and the moment may have seared itself into his memory, as it did for many Americans who remember the news breaking that day.

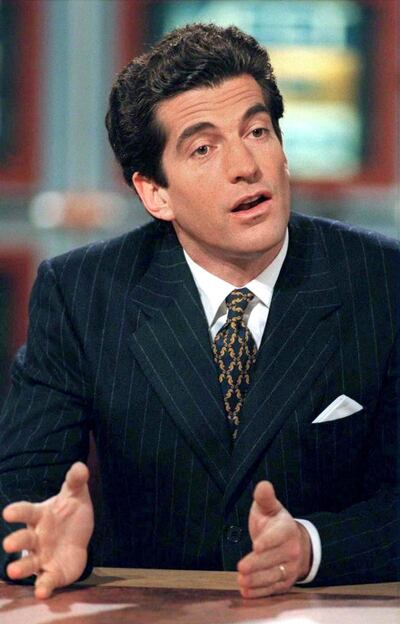

And there are other odd things about The House of Kennedy. The book purports to be the "true story" of the Kennedy family, from paterfamilias millionaire Joe Kennedy to his tragic trio of oldest sons, Joe Jr (killed in action during World War II), John (slain as president in 1963), and Bobby (slain as presidential candidate in 1968) to surviving son, Senator Edward Kennedy and such famous next-generation scions as John Kennedy Junior.

But this account is entirely based on public documents and popular secondary sources; no Kennedy “true stories” are told here that haven’t been told for decades.

At its heart, the book is a quick, readable tour through the lurid highlights of the Kennedy family’s past. Readers are served up generous portions of both fact and rumour, all of it delivered in exactly the kind of telegraphic, fast-paced present-tense prose that has characterised Patterson’s fiction for 40 years.

For instance, when the subject of Joe Jr's affair with Broadway actress Athalia Ponsell comes up, Patterson writes: "Ponsell is best known in later years for her grisly – and unsolved – murder in 1974, when she was found decapitated by machete outside her home in Florida."

Before the reader can even register the fact the murder took place 35 years after the affair, the book goes on: “She later becomes the subject of two true crime books, as well as lingering questions about the cost of romancing a Kennedy.” It is Patterson’s salacious innuendo that wins the spotlight.

This isn't exactly how history is supposed to be written