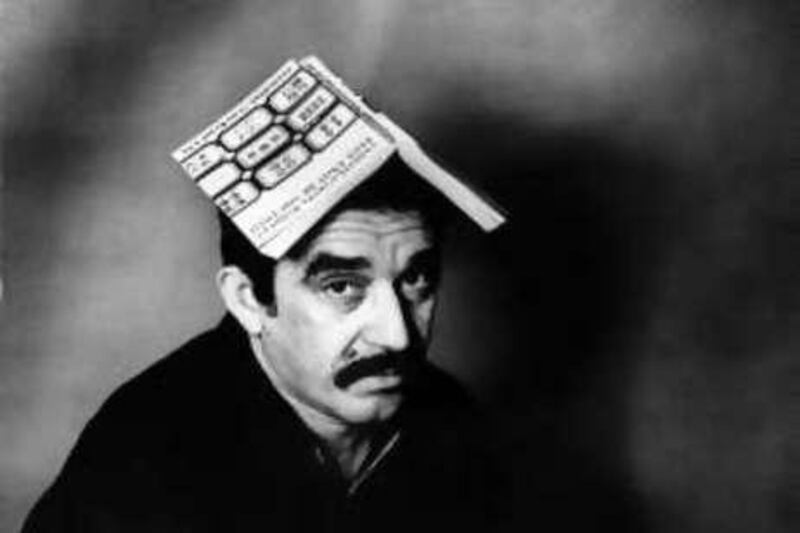

Nobel Laureate and friend to Castro and Clinton, Gabriel García Márquez bestrides the world and feigns innocence. Russell Cobb reads a new biography of fiction's very old man with enormous strings attached.

Gabriel García Márquez: A Life

Gerald Martin

Bloomsbury

Dh140

There is widely circulated story, perhaps apocryphal, about a young Albert Camus meeting a boozy William Faulkner at a cocktail party in post-war Paris. Camus was desperate to speak with the American novelist, with whom the French literati had become obsessed. But Faulkner demurred, claiming to be just "an old farmer from Mississippi" - a response typical of his publicity-shy, literary outsider persona. It is hard to imagine a celebrity writer with as many political commitments as Gabriel García Márquez wiggling his way out of controversy by taking a similar tack. And yet, when pursued by journalists with prickly political questions, he has been known to feign ignorance, claiming he is "just a mediocre notary."

García Márquez towers over the field of Latin American letters in the 20th century. Not only is he a Nobel Laureate, a best-selling author and a close friend of Fidel Castro, he has also worked to revitalise investigative journalism throughout the continent and even advised Bill Clinton on foreign policy. And yet, as Gerald Martin's new biography of García Márquez demonstrates, the Colombian has always tried to be both conspicuous and enigmatic. As an author, he has cultivated the image of a secretive literary master craftsman - the "Master of Macondo" and the "Magician of Melquíades" - never willing to reveal his "tricks." As a politician, the man universally known as "Gabo" is even harder to pin down. While García Márquez has a attained "a kind of roving presidential status," according to Martin, his political commitment to worldwide socialist revolution has waxed and waned. "Yes, García Márquez is a like a head of state," Castro has said. "The question is 'which state?'"

For a region with a relatively underdeveloped high-culture infrastructure (no wealthy universities, few prestigious magazines, no flourishing book trade), Latin America has produced a number of public intellectuals from the world of arts and letters. Before García Márquez, there were Pablo Neruda and Miguel Angel Asturias, men whose utterances were followed in the press like the erstwhile "oracle" Alan Greenspan in the US. The traditional path to public intellectualdom in Latin America is achieved through international diplomacy. Asturias, Neruda and Carlos Fuentes all spent time in their respective country's diplomatic corps, learning from avant-garde movements in France and using the cultural capital acquired in Europe for prestige at home. Until the Gabo phenomenon exploded along with the Latin American Boom in literature in the 1960s, cultural capital was inversely proportionate to actual capital. (For a revealing look at the curious link between intellectual prestige and money, read Pascale Casanova's The World Republic of Letters).

Gabo's humble origins make his success even more compelling. He was born the son of a telegraphist in a backwater called Aracataca near the Caribbean coast in 1927 with little connections to the intellectual elite of Colombia. His father, Eligio García, was a conservative man about town who left a trail of illegitimate children behind him. The parents left the son to be raised by his maternal grandparents. It was from his grandfather, a retired colonel and Liberal partisan, that Gabito got his first lessons in storytelling and politics. The colonel told Gabito about the Thousand Days War and the invasion of the gringos and their massacre of striking United Fruit Company workers in 1928. Later, Gabo struggled through law school in Bogotá, trying his hand at journalism and living hand-to-mouth, visiting prostitutes even when he was broke (the inspiration for García Márquez's last novel, Memory of My Melancholy Whores).

Although Gabo learned to resent the gringos as a kid, Martin says that he idolised Hemmingway from early on. Later came the inspiration from Faulkner, whose native Mississippi soil he visited on a Greyhound bus in the early 60s. His first big break in journalism came in a bustling, scruffy coastal city, Barranquilla, "a place with almost no history, with almost no distinguished buildings," according to Martin. "But it was modern, entrepreneurial, dynamic and hospitable." It was a place that suited Gabo's simultaneous intellectual curiosity and disdain for intellectualism. "Barranquilla enabled me to be a writer," he tells Martin. "It had the highest immigrant population in Colombia... An open city, full of intelligent people who didn't give a f*** about being intelligent."

After Barranquilla, Gabo found himself in Paris, still then the beacon for disaffected Latin American intellectuals. Ostensibly on assignment for a Liberal newspaper, El Espectator, García Márquez mostly scrounged around for food and women, trying to stay warm and write a novel. Although Martin expresses little interest in exploring Gabo's "secret life", he tells the story of his fateful love affair with an attractive Spanish exile named Tachia, who later aborted García Márquez's child. At this point, García Márquez is at loose ends, hoping to marry Mercedes Barcha in Colombia, but without enough money (or desire) to return to his native land.

The turning point in Gabo's life, according to Martin, was the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967. Up until that point, García Márquez, then 40, was a peripatetic journalist then living in Mexico, his adopted country. El Espectator had been shut down by a conservative government, and Gabo often survived off the kindness of strangers. He had published one novel - Leaf Storm - a decade before, to little commercial success. In 1966, Gabo and his wife Mercedes went to the post office in Mexico City to mail the manuscript to Buenos Aires. The couple, Martin writes, "were like two survivors of a catastrophe. The package contained 490 typed pages.

"The counter official said: '82 pesos.' García Márquez watched as Mercedes searched in her purse for the money. They only had 50 and could only send half the book: García Márquez made the man behind the counter take sheets off like slices of bacon until the fifty pesos were enough." Mercedes then pawned off her hairdryer and a few other items so they could send the next instalment. This incident, like so much in Gabo's life, might be hyperbole. It does bear a striking resemblance to something from No One Writes to the Colonel, in which a retired colonel finds himself scraping rust from his coffee tin just to stretch the last few grinds.

For a relatively low-profile author, the reaction to One Hundred Years of Solitude was surprising. Unlike the Latin American vanguards that came before him, García Márquez had no sweeping manifesto he wanted to disseminate with the publication of this book. He had a vague commitment to socialism, ("I am a communist who has not yet found a place to sit," he once said) but so did every other Latin American writer of note (except for the anti-political Borges). Neruda, who was at the pinnacle of his popularity, declared One Hundred Years of Solitude to be "one of the best novels in the Spanish language." At the time, a successful print run of a Latin American novel would have been a few thousand copies. The publisher upped the print run of Solitude to 20,000, but those quickly ran out. Carlos Fuentes, who was already a one-man literary institution, praised the novel as the "Bible" of Latin America.

How Gabo managed the ensuing celebrity, recreating his public persona, forging friendships with the powerful and reworking his style as a "magical realist" is the subject of the second half of Martin's book. Many anecdotes will be familiar to Gabo fans, and might disappoint those looking for juicy details about his private life (Martin writes that the Colombian has lived three lives: one public, one private and one secret. Martin has captured the public life as exhaustively and faithfully as any biographer could hope to. Of Gabo's private life, we catch glimpses; of his secret life, only hints.)

As Gabo achieved celebrity, the breakdown of his friendship with the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa came to represent the fraying of the Latin American literary establishment. Both men spent the 1960s as "committed" writers, fervent supporters of the Cuban Revolution. As the Revolution took a Stalinist turn in the 1970s, Vargas Llosa distanced himself from Castro while García Márquez worked to put himself in the good graces of Cuban authorities. In what is probably the most famous fight in Latin American literature, Vargas Llosa floored Gabo with one punch in 1976. Although the fight was not about Cuba (it was for something that Gabo did or said - Martin isn't sure - to Mrs Llosa), it was proof that an era of literary and political common cause was over.

Martin - like many English-speaking admirers - seems slightly torn about his subject's incomparable literary talent and his shifting public persona. Each chapter contains insights into García Márquez's books, for which Martin expresses his admiration. Like many critics who have studied García Márquez, however, Martin seems unable to reconcile his subject's advocacy for press freedom in Latin America with his undying love for Fidel Castro. Indeed, Gabo's relationship with Fidel is one of the most curious friendships in history. Again, here, Martin had to strip away layers of chisme (rumour) to separate fact from fiction. Fiction: Gabo sends his manuscripts to Fidel for approval before he publishes them. Fact: Gabo has remained a (if not the) close personal friend of Fidel and has never publicly condemned him, even after the Cuban government ordered the execution of one of Gabo's friends on dubious drug trafficking charges.

The argument Martin eventually arrives at is that Gabo - after decades as a starving writer and a literary outsider - became obsessed with power. In Martin's reading, Gabo is not so much someone who is naive in his political beliefs (as many of his critics, including Reinaldo Arenas, have charged) but someone who derives inspiration from access to influence. In 2007, a frail and sick García Márquez appeared at a meeting of the Inter-American Press Association. His old friend Bill Clinton was there, as was the King of Spain, whom he addressed as "Tú." Martin writes:

"Once again, it had been demonstrated that if García Márquez was obsessed with - fascinated by - power, power was repeatedly irresistibly, drawn to him. Literature and politics have been the two most effective ways of achieving immortality in the transient world that western civilisation has created for the planet; few would hold that political glory is more enduring than the glory that comes from writing famous books."

Martin's take on Gabo - that his relationship with Castro was a two-way street - would also explain the writer's relationship with Clinton, who sought out the Colombian despite Gabo's numerous anti-American comments. Gabo's critical and commercial success, in addition to the immeasurable amount of cultural capital he gained by winning the Nobel Prize in 1982, meant that he could bend the ears of the powerful. Rarely, however, has Gabo's access to power achieved much. His unique access to Castro and Clinton never translated into any progress on US-Cuban relations. Even though Colombian drug lords sought his autograph while Colombian presidents sought his endorsement, he has been unable to do anything about the country's decades-long civil war known simply as La Violencia.

While Martin traces these and many other contradictions in Gabo's public life, he always returns to the works. Time after time, García Márquez remade Latin American literature, bucking trends and surprising critics. After the quasi-mythological fable of Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabo spent years crafting Autumn of the Patriarch, the ultimate dictator novel - a fairly established Latin American form - whereas he could have easily ridden the magical realist gravy train to commercial success in the US, where publishers were dying for more exotic Latin magic.

Perhaps most astonishingly, Gabo returned to investigative journalism in his late 60s, with the publication in 1996 of News of a Kidnapping, a work that reads like In Cold Blood set in the drug wars of 1990s Colombia. But it his mastery of the novel - fiction and non-fiction - that will be García Márquez's enduring legacy. The political theatre, the self-effacing claims of being a mediocre notary, the chisme that fuels the Latin American press: with the impending mortality of García Márquez (Martin says that he wanted to publish the book before the author's death), all of these things will fall away. Gabo's fictions, its gypsies and very old men with enormous wings, will endure.

Russell Cobb is an assistant professor of Latin American studies at the University of Alberta. He is working on a book about the politics of the Latin American literature boom.