The Blind Man's Garden

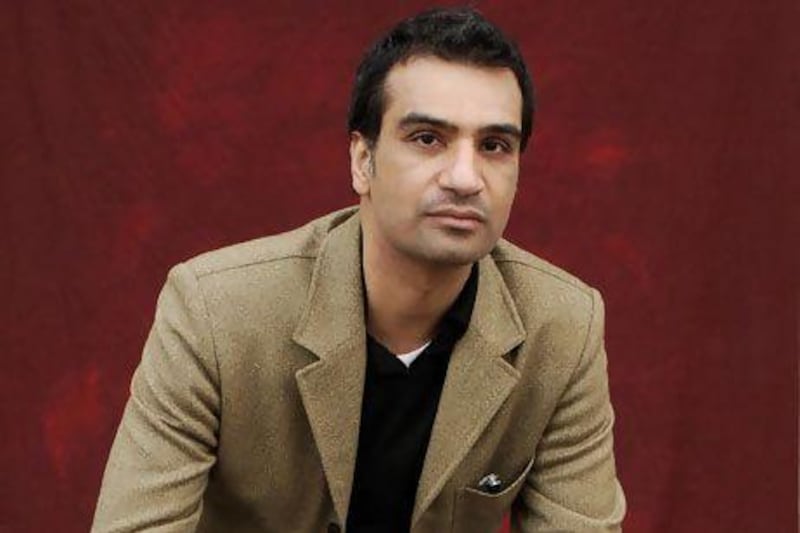

Nadeem Aslam

Faber & Faber

"History is the third parent." This is the opening line of Nadeem Aslam's new novel The Blind Man's Garden. Aslam suggests in his powerful and quite astounding fourth novel that while there is no escaping the "parentage" of history, we can in the course of our lives follow and negotiate with the workings of our historical circumstances. Set in Pakistan and Afghanistan in the months after the September attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Aslam steps right into the middle of the battleground where the repercussions of these attacks in the West are causing human carnage and devastation.

Aslam's first novel, Season of the Rainbirds (1993), was a quiet journey into the lives of people in a small Pakistani village in which he explores the tensions between a traditional Islamic way of life and modernity. His second novel, Maps for Lost Lovers (2004), was long-listed for the Booker Prize and was about a Pakistani community based in England and the ordeals and sufferings that come with exile. With his third novel, The Wasted Vigil (2008), Aslam bravely stepped into wider territory by exploring the devastation of the war in Afghanistan. In The Blind Man's Garden, Aslam continues to write in the same territory as his previous novel and attempts to explore the trauma, the tragedy and the mass devastation of not just the innocent in Afghanistan but in neighbouring Pakistan, which is found reeling under its own inner divisions.

Rohan, a retired teacher, lives in an old house in the small town of Heer in Pakistan, surrounded by his exquisite garden where "the scent of the tree's flowers can stop conversation" and in which "Rohan knows no purer sense of melancholy". The house, once part of a school, was created from Rohan's own patronage to scholarship and the virtues and magnificence of six cities that he considered to be examples of the grandeur of Islam: Mecca, Baghdad, Cordoba, Cairo, Delhi and Istanbul. "From each he brought back a handful of dust and he scattered it in an arc in the air, watching as belief, virtue, truth and judgment slipped from his hand and settled softly on the ground". The garden, Aslam's metaphor for the world, a place of beauty and innocence, is in the course of the novel corrupted and tarnished with innocent blood.

As the story unfolds, Rohan's son Jeo and his foster brother Mikal are planning a journey into war-torn Afghanistan, "wishing to be as close as possible to the carnage of this war". Rohan, accompanying them as far as Peshawar, is unaware of the intentions of the two young men. Once in Peshawar, they leave the elderly Rohan and secretly cross the border in order to aid the wounded in Afghanistan. In this unforgiving territory, Jeo is killed and Mikal is taken prisoner by a Taliban warlord. In one of the most exquisite examples of Aslam's inimical prose in the novel, of which there are many, is the moment of Jeo's death. "How easy it is to create ghosts," he thinks as he begins to die a minute later, feeling his mind closing chamber by chamber, the memory of Naheed contained in each one. And despite it all it means much to have loved.

Back in Heer, Jeo's wife Naheed waits for his return and that of Mikal, with whom she shared a past relationship before she married Jeo. Here Aslam skilfully begins to weave in moments from history with the doomed love story of Mikal and Naheed. As Jeo's dead body is returned unceremoniously to the gates of his father's house, the imprisoned Mikal remains unaware of the fate of his friend. Rohan himself returns from Afghanistan, where during his search for Jeo and Mikal he is blinded in his attempt to rescue a young boy from the clutches of a warlord. The garden around him, tended lovingly over the years, slowly disappears from his sight.

Mikal, believing Jeo is still alive, begins to search for him while still a prisoner. In Mikal's tortured and agonising search for his friend, Aslam crucially validates the shared atrocities of Americans, Afghanis and Pakistanis and the ensuing devastation in their pursuit of misguided justice. "They want the birth of a new world, and will take death and repeat it and repeat it and repeat it until that birth results."

Aslam writes with an unflinching nerve about the frenzied ruthlessness in human nature brought about by war. Whether it is in his depiction of young boy soldiers being mass raped in a Taliban warlord's prison, or by the US army when they try to extract information from prisoners by torture, Aslam's images and descriptions are often realistic and unsettling. It is remarkable how at the same time he manages to take the beautiful and the sublime and place it in such unnerving proximity to the brutal and horrific. At times, though, it can be awkward to adjust to Aslam's style and his eagerness to illustrate the sharp contrast between the receding world of beauty and the unspeakable horrors of war.

Aslam's characters are complex and intricate. Mikal, quiet and strong, pursues his faith and friendship and his love with strength unknown even to himself. Naheed, equally resilient, waits for him patiently. It is Naheed who looks after Rohan as he slowly goes blind, even painting each flower in the garden so that he is able to see the glimmer of colour through his fading vision. Rohan, tortured by mistakes he had made in the past, stoically accepts his loss of vision. Some secondary characters, such as Mikal's brother Basie and sister-in-law Yasmin and Naheed's mother Tara, who come into full focus in the latter half of the novel, are perhaps not as well developed as desired, but Aslam nevertheless keeps them as minor but pivotal joints within the plot.

The final third of the novel feels heavy and at times awkwardly divided between masterful prose and a sudden sagging of the plot. Just as the reader sits back satisfied that Mikal has returned to Heer, even though he is a fugitive, Aslam decides to send him away again on an ill-fated mission. In spite of this slight deviation towards the end, there is a delicacy of tone on display in The Blind Man's Garden that heightens the expansive theme more than has been seen in any of his previous novels. While Aslam meticulously documents the savagery of Afghanistan and Pakistan, leaving far behind the subtle lyricism of his first novel, the exquisite tapestry of his prose continues to enthral the reader, drawing one closer to the hard truth by the starkness of his contrasts.

At its heart this is a novel encumbered with a need to recognise the unnecessary destructive impulses that drive us and which so often detract from the pursuit of love. The Blind Man's Garden definitely does not fall short of being another of Aslam's successful novels and in parts can even be said to have the makings of a masterpiece.

Erika Banerji has written and reviewed for The Statesman, The Times of India, The Observer and Wasafiri. Her short fiction has been published in several international literary journals and won the runners up award in the Mslexia short story competition in 2012.