How does Anne Tyler get it so right, book after book, as she examines the motivations and emotions of daily life? Not only that, but she wields her tools with barely a wasted word or clichéd character.

Now add her newest novel, The Beginner's Goodbye, to an impressive and long oeuvre that also includes Breathing Lessons (winner of the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for fiction), The Accidental Tourist (winner of the 1985 US National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction), and two Pulitzer finalists.

The Beginner's Goodbye isn't perfect. At barely 200 pages, it's perhaps too concise, and the plot development has a couple of noticeable imperfections. However, those failings are far overshadowed by the sheer pleasure of savouring Tyler's craftsmanship as she subtly and gradually prompts her narrator, Aaron Woolcott, to face the truth of his reactions to his wife's sudden death.

Aaron is an editor at his family's well-established but struggling publishing company, located in Tyler's trademark setting, the decaying city of Baltimore, Maryland. The company is propped up by two barely profitable product lines, a vanity press and a series of narrowly focused self-help books with such wonderful titles as The Beginner's Spice Cabinet and The Beginner's Cancer - which is, obviously, how this novel gets its own title.

The staff at Woolcott are a quirky, original lot, including the secretary, Peggy, who dresses in ruffles and bakes chocolate chip-oatmeal-soy cookies, and the designer, "tall and ice-blonde" Irene Lance, who reminds Aaron of a character in the Ingmar Bergman movie Wild Strawberries. Aaron himself is a typical Tyler hero - a loner and a loser, middle-aged in spirit if not in years - but he also has his unique qualities. As he too-offhandedly reveals, "I have a crippled right arm and leg. Nothing that gets in my way ... Oh, and also a kind of speech hesitation, but only intermittently."

A few years back, to his family's dismay, Aaron had married the frumpy, no-nonsense radiologist Dorothy Rosales, eight years older than he. She was "short and plump and serious-looking", prone to wearing "wide, straight trousers and man-tailored shirts, chunky crepe-soled shoes of a type that waitresses favoured in diners" - but, he insists, "I don't think other people recognised how attractive she was, because she hid it." Well, to be honest, he later admits: "If she had properly valued me, wouldn't she have taken more care with her appearance? ... As the months went by, I found myself noticing more and more her clumsy clothes, her aggressively plodding walk, her tendency to leave her hair unwashed one day too long." And maybe, in the wedding photo, her blue knit dress is not particularly flattering?

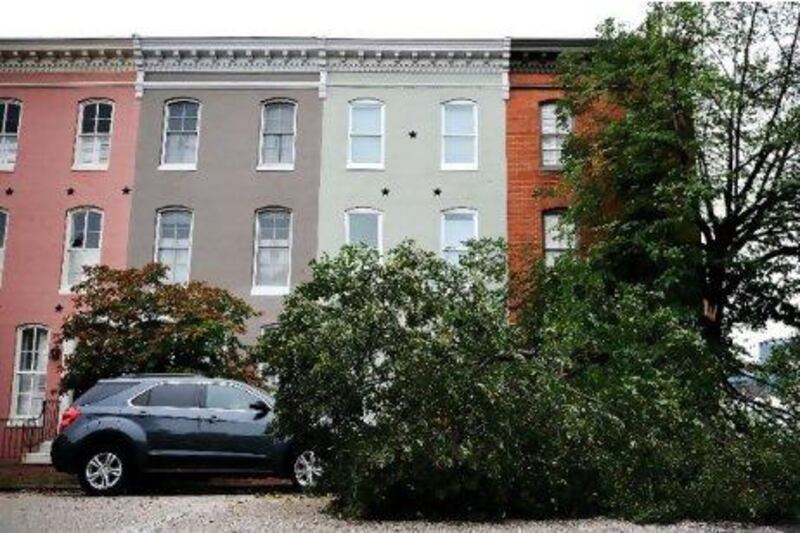

In the midst of a quarrel over Dorothy's desire for a certain brand of cracker to snack on, while she and Aaron are each sulking in different parts of their house, she is seriously injured in a freak accident when a tree crashes into the building, and she dies a few days later. Aaron is genuinely grief-stricken. Hibernating, he refuses all manner of well-meaning sympathy. However, after a rainstorm exposes the huge leak in his roof, he is compelled to move in with Nandina, his domineering older sister.

Then one day, when Aaron decides to visit his house for the first time in weeks, he sees Dorothy.

"She watched me intently as I came nearer, with her chin slightly raised and her eyes fixed on mine ... I thought I would never in all my life smell a more wonderful combination than isopropyl alcohol and plain soap."

This image is just one example of Tyler's exquisite touch, blending the concrete and humdrum with the mystical return from the dead.

In later scenes, Dorothy shows up at ordinary moments, while Aaron is shopping for lettuce at the local farmers' market and waiting on a bench at the mall for Nandina.

Some readers may think that they would have handled these encounters better, leaping to wrap their loved ones in tight hugs and pummeling them with important questions: "Are you back for good? What is death like?" or even: "Why didn't you ever tell me about your ex-boyfriend?" But Tyler knows better. Aaron is wary; he doesn't want to scare Dorothy away. He's also in shock. So it takes a while before he risks a conversation. And when the husband and wife finally start talking, it turns into a mundane squabble over cookies.

Well, of course. Isn't that what relationships are like in the living world?

Presumably, Dorothy's appearances - and even her revelation of a couple of secrets - are just Aaron's imagination, or, more to the point, the personification of his need to somehow make peace with the fact of her death. That adjustment has been especially difficult for him because he and Dorothy had been mired in their argument when she was crushed by the falling tree. What difference does it make if Aaron now insists that these posthumous visions are real? Don't we all wish we had such a second chance to explain, to reconcile, to say "I love you" after someone important to us has died? Tyler has simply found a creative way of displaying this universal human emotion.

But that very strength - the insight and originality of Dorothy's reappearance - ironically underlines one of the book's main flaws. It takes a tad too long for the post-death Dorothy to arrive. After a tease at the beginning, she doesn't show up again until almost two-thirds of the way through the novel. If a story is going to centre around such a dramatic development, then the reader needs to see more of it.

The second problem is that some of the subtle plot seeds are planted a little too overtly. Occasionally - as with Dorothy's frumpy appearance - the foreshadowing is too obvious. On the other hand, nothing ever comes of the hint that Aaron is jealous when Nandina develops a budding romance with the contractor who is repairing his house, even as Aaron is mourning his own lost love.

The concept of working at a vanity press may be too easy of a target and, moreover, has been used before, in Alice McDermott's 1982 novel, A Bigamist's Daughter. Still, Tyler has so much fun with her imaginary publishing house that it's hard to complain.

If this plot isn't as inherently dramatic as the tales in some of Tyler's other books, such as Earthly Possessions, where the heroine is kidnapped, that's exactly the point. Despite the ghost story, The Beginner's Goodbye is actually about real life. Indeed, the title is perfect. This is a guide to mourning and letting go, and a far better one than poor Woolcott Publishing could ever produce.

Fran Hawthorne is an award- winning US-based author and journalist who specialises in covering the intersection of business, finance and social policy.