In 2009, the square outside the national theatre in Sarajevo got a new name: Theatre Place – Susan Sontag. That the American writer and filmmaker, who died in 2004, is lauded in the Bosnian capital is testament to how far her influence spread beyond the confines of cultural theory and academia.

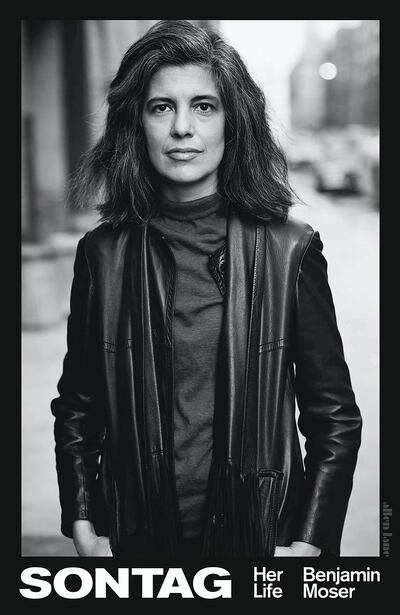

The author of Against Interpretation (1966) and On Photography (1977) is a prime candidate for biography and a new 700-page book by Benjamin Moser barely lags as it explores Songtag's complex personality, work and legacy. Sontag became a cause celebre in 1964 after the publication of her essay Notes on Camp in Partisan Review, which was popular among America's liberal intelligentsia. The text was an argument that popular culture should be treated seriously – a love letter to "artifice and exaggeration", as Sontag put it – that amounted to an attack on the old guard that still dominated the publishing houses and museums of the US.

If Sontag was seeking a reaction, she got it. Mosur quotes art critic Hilton Kramer, who bemoaned how Sontag had "severed the link between high culture and high seriousness that had been a fundamental tenet of the modernist ethos". Instead, Notes on Camp heralded the postmodern era. It is no surprise that within a year Sontag was invited to Andy Warhol's New York studio, The Factory, and appeared in one of the artist's "screen test" videos, with both writer and artist wearing sunglasses as they hung out.

Sontag's fame lasted longer than 15 minutes. The bookish girl, who was dragged from town to town across America by her widowed, alcoholic mother, and whose intelligence meant she found making friends difficult, fell into a life of celebrity. "She herself became a symbol of New York," Moser writes.

But fame did not sit easily with Sontag. "Throughout her life, success would always unsettle her more than failure," Moser says.

This biography was authorised by Sontag's estate and Mosur was able to speak to important people from the writer's life, from photographer Annie Leibovitz to artist Jasper Johns. Mosur is evidently a fan of Sontag's work, yet remains brutally honest in his assessment of both her professional and personal failings.

Amid the praise for her seminal texts, Monsur unpicks a work she produced after a visit to Vietnam in 1968. "To see the world as an aesthetic phenomenon is to exclude the impact of politics, ideology, human action," Moser says. Her writing from Hanoi can be criticised as a bland report of Vietnam as per the American imagination, as opposed to a portrait of the country in that moment.

By the 1990s, she had beaten cancer once (it would return and was the cause of her death at the age of 71) and had written Illness as Metaphor (1978), which Mosur argues convincingly had the greatest impact outside the world of arts and letters among all of her work. That cancer patients are regarded (not always unproblematically) as heroic and the disease is not thought to be the result some moral failing is, at least in part, down to Sontag. It seems unbelievable now that the latter view would be considered viable at all, but in her text Sontag quotes from the work of German author Thomas Mann (a childhood hero) and contemporary writing in the field of psychology that revealed bewildering superstitions about the disease.

That Sontag's life had been in danger fuelled the empathy she felt towards the people of Bosnia during the country's vicious sectarian conflict. Sontag first visited the country at the start of the conflict in 1992 at the suggestion of her son, David Reiff, who was a foreign correspondent at the time.

Moser is unstinting in his praise of Sontag, who went to the country 11 times, as are the Bosnians interviewed in the book. "If praise and prosperity brought out the worst of her, oppression and destitution brought out the best," he writes.

Her decision to stage a production of Samuel Beckett's play Waiting for Godot in a place with barely any electricity, little food and bombs raining down is certainly remarkable. The way Moser describes it, it seems the most incredible production of the play, or any play for that matter, that has been staged anywhere, at any time. It brought intellectual relief to those living amid the war, as well publicising the ethnic cleansing being carried out in Bosnia at the time. The headline on the front page of the Washington Post the next day was "Waiting for Clinton".

Moser is perhaps too exhaustive in his account of the various New York society intrigues and spats Sontag had throughout her life, as they are really only of interest to people captivated by literary gossip. Moser is no stranger to such altercations himself, played out recently in the letters pages of various literary journals.

The biography really comes alive, and Sontag seems at her most endearing, when we encounter this famous citizen of New York outside that most self-obsessed of cities. In person she could, it seems, be monstrous, but her legacy is surely indisputable.