The Corpse Washer

Sinan Antoon

Yale University Press

There exists an unwritten rule in book reviewing, one particularly adhered to in transatlantic publishing circles, which states that a critic should either say good things about a debut novel or nothing at all. A fair deal is not encouraged, it is required. The fledgling writer deserves a chance after enduring his or her long creative slog and sweating out the further ordeal from pitch to publication. For the critic, a rigorous critical dissection, even a hatchet job, may only begin with the second novel, when the writer under scrutiny is considered tough enough to weather the blows. Critics, hitherto held back, feverishly sharpen their nibs to skewer that difficult second novel, one that invariably arrives in the shadow of its more accomplished predecessor. Many a writer falls at this hurdle, cut ruthlessly back down to size and forced to prove their credentials all over again.

The Corpse Washer is the second novel by the Baghdad-born, New York-based writer Sinan Antoon. But make no mistake: this is no difficult second novel. The Corpse Washer is a remarkable achievement, a novel that comes with the unerring confidence of an assured debut and the accomplished air of a mid-career high. Indeed, Antoon seems to just get better and better, his third novel, Ya Maryam, being recently shortlisted for the 2013 Arabic Booker Prize. Antoon is also an acclaimed poet and translator, as The Corpse Washer testifies: Antoon has expertly translated it into English from the original Arabic without sacrificing its lyrical cadences or, as is often the case in translation, pressing too hard to convey imagery. The result is a compact masterpiece, a taut, powerful and utterly absorbing tale that, with luck, will secure Antoon a wider, more international readership.

At the heart of his novel is Jawad, our protagonist, born to a Shiite family of corpse washers and shrouders in Baghdad. He takes us through his life, intercutting past with present and overlying both with snapshots of nightmares brought on by the choppy waves of violence that engulf his city and the growing number of dead bodies that pass through his wash house. "If death is a postman, then I receive his letters every day," runs one of many artful metaphors. "I am the one who opens carefully the bloodied and torn envelopes. I am the one who washes them, who removes the stamps of death and dries and perfumes them, mumbling what I don't really believe in. Then I wrap them carefully in white so they may reach their final reader - the grave."

But Jawad takes us back and explains that mghassilchi - body washer - was not his intended vocation. He recounts his apprenticeship with his father and recalls his military service, at the same time stressing his love of art and desire to sculpt and craft. Flouting his father's wishes, Jawad enters Baghdad's Academy of Fine Arts where he meets and falls for the alluring Reem. Family strife and death are eclipsed by art and love. But the serenity is short-lived, a calm before the Desert Storm. War breaks out, then economic sanctions inflict further damage on the Iraqi people. Jawad scrimps and struggles and loses loved ones but manages to stay afloat. However, as he learns to his cost, these hardships are a mere preamble. The 2003 invasion deposes a tyrant, promises peace but ends up triggering sectarian slaughter. Amid the brutality - indeed as a result of it - Jawad has no choice but to abandon his chosen career path for the mghaysil and the work originally designated for him. Suddenly, that postman of death is bringing more letters than ever before. Love is sidelined for duty, art is shelved for death as Jawad faces up to dark, new challenges and conflict within his tortured soul.

The Corpse Washer is no breezy beach-read but it is by no means all doom and gloom. Candid rather than cheerless, it offers a valuable portrait of the city as a battlefield, of life under fire and the resilience of the human spirit. This is the war on terror up close, and from the unenviable vantage point of a civilian cleaning up the mess while having to keep his own head down. Jawad reports on suicide bombings and reprisals between Sunni and Shiite militias; museums and banks are looted, mosques torched; people disappear and come back disfigured, dismembered or not at all. One curt but long-enough vignette describes Jawad watching terrorists behead a hostage on TV, and it is all the more hard-hitting for being unexpected, a stand-alone flash of grisly horror with no link to what comes immediately before or after.

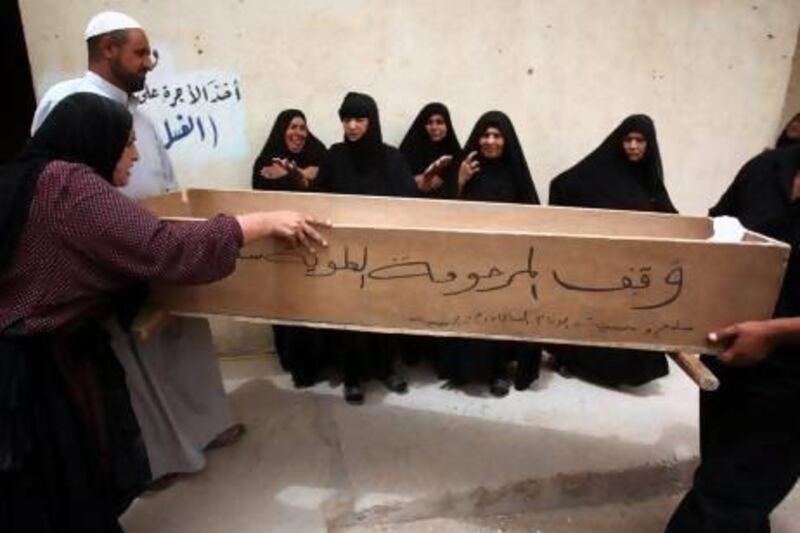

Antoon ensures the violence goes full circle, and, in places, renders it as near-farce. At one juncture Jawad and his friends are driving Jawad's just-dead father in a coffin to a burial site. "Only a mad person would want to be inside a moving car while bombers and fighter jets were hovering overhead, ready to spit fire at any moving object." They are halted and searched by an American platoon that suspects them of being suicide bombers. The scene is laced with tension - can they convince the trigger-happy Americans they pose no threat? - but the inherent desperation also prompts us to view it as manic slapstick. Elsewhere, what humour we get is pitch-black and sufficiently mordant. Jawad tells how "we got ready for wars as if we were welcoming a visitor we knew very well, hoping to make his stay a pleasant one".

As if the violence during the day wasn't enough, Jawad is wracked by debilitating nightmares. Henry James said that to tell a dream is to lose a reader but Jawad's reveries never grate. What's more, they are not presented as dreams but as reality, with lines such as "I start to suffocate, then bolt awake" jolting us back to normality, albeit one that is at times scarcely distinguishable from Jawad's nightly terrors.

Antoon is equally impressive with his detail. The practice of corpse washing is initially hidden from the young Jawad who is fobbed off with a series of evasions every time he enquires about his father's profession. When he learns his trade, the reader learns with him, and there is pleasure to be had in gleaning its arcane rituals. It is during the washing and shrouding scenes that Antoon is at his most subtle, conveying volumes about characters with the lightest strokes. One corpse arrives with interesting scars, another with clenched fists. A man brings Jawad a severed head to wash and Antoon excels first by jarring us with the description of it, and then moving us with the circumstances of the victim's fate.

The rare occasions when the novel fails to engage can be attributed to Antoon jettisoning that subtlety. He is right to have his characters bemoan their country's shambolic occupation and rage that "these liberators want to humiliate us". Jawad's colourful Uncle Sabri declares the Americans inept, irresponsible, ignorant and racist and is certain they "will make people long for Saddam's days". Corpses pile up "like goals scored by death on behalf of rabid teams in a never-ending game". The analogy works, a variation on death-as-a-postman - until the tone wavers: "The American referee had killed enough already and now was killing only sporadically, allowing the local players, who were even more ferocious, to carry on."

That single word "allowing" upends all that carefully accrued subtlety, tipping Antoon's deft legerdemain into clumsy heavy-handedness. Is this active sanctioning on the part of the Americans or passive negligence? Antoon's stance is not the point; what matters is his calibrated subtlety has been traded in for an unwelcome note of stridency. Jawad's cool narration falters and he begins to feel less his own person and more the author's puppet and mouthpiece.

"The Angel of Death is working overtime, as if hoping for a promotion, perhaps to become a god." Lines such as this set the novel back on track - lines that illustrate and impress and inform without banging a drum. The Corpse Washer tells a horrific tale but also a poignant one. Jawad had hoped his statues would one day populate the city; instead it is corpses "scattered all over the streets and stuffed in fridges". Will he escape, as he longs to, over the border into Jordan, or is his future to be spent purifying and shrouding the dead in "Baghdad's stabbed heart"? Antoon keeps us guessing - and marvelling - right up to the last pages, pages that are quietly but unmistakably suffused with an ever-welcome sign: hope.

Malcolm Forbes is a freelance essayist and reviewer.