On the surface, Emma Donoghue's latest novel, Akin, has much in common with her most famous work, the Booker Prize-shortlisted Room. Both are set in the present (most of Donoghue's novels and stories unfold in unique historical pasts). And both are largely intimate and at times intense two-handers that revolve around an older and younger family member and their shared connections and individual struggles.

But while Room was a dark, claustrophobic tale about the imprisonment of a mother and her five-year-old son, Akin turns out to be a sunnier, more entertaining affair that flings together two distant relatives and then follows their progress on a holiday in the French Riviera.

Not that it is a cloud-free story of sweetness and light. The age gap and sociocultural divide between Noah, 79, and his 11-year-old great-nephew Michael remain constant sources of friction. And as the pair take in sights and endure each other's company, secrets from their family's past emerge and cast long shadows.

Donoghue begins in New York with Noah, a widowed and recently retired professor, preparing for a return visit to Nice. He hasn't been to his home town since he was four. Now, as his 80th birthday approaches, he intends to reacquaint himself with the city and, with luck, discover what happened to his mother during the Second World War.

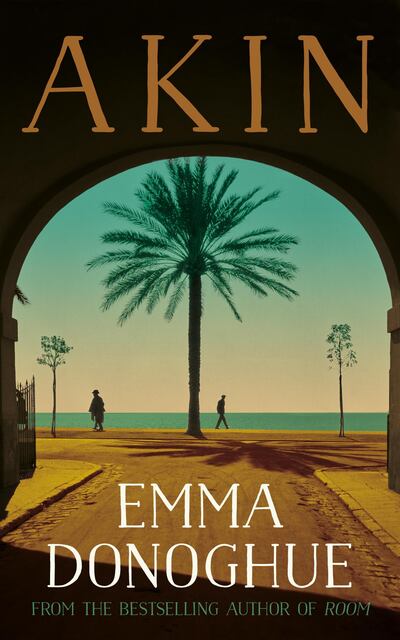

It's here! Books take so much longer to make than babies, in my experience, I can never quite believe one of mine is going to come out till I open the box. Publication Sept Canada/US, Oct UK/Ireland. Thanks Margaret Lonergan for the gorgeous cover. #Akin pic.twitter.com/uQiFnKttmG

— Emma Donoghue (@EDonoghueWriter) August 21, 2019

A phone call out of the blue threatens to jeopardise Noah's best-laid plans. A social worker informs him that, owing to a recent death, he is now the last of Michael's kin.

Can he give him a temporary home? Noah's initial bemusement ("In what sense could you really be kin to someone you'd never met?") gives way to reluctance to help, especially on hearing that his "oppositional" great-nephew "makes bids for negative attention". In the end he takes the boy in, then takes him along to France.

So commences a bumpy ride. Michael is sullen, insolent and foul-mouthed. Noah gives his charge the benefit of the doubt: he is surely off-balance and out of sync because he is jet-lagged, culture-shocked and has recently lost his grandmother.

Despite Noah's best efforts, with each passing day Michael shows only flickers of friendliness, and for the most part stays glued to the games on his phone and indifferent to his new surroundings. After a while each saps the patience of the other. Donoghue keeps Noah's frustrations to himself: "What merciless fate had decreed that Noah turn 80 in this brat's company?" Michael, on the other hand, airs his annoyance in angry put-downs: "It'd take more than a couple spirals of DNA to make us blood."

Fortunately, Donoghue resists giving her reader a neat and tidy turnaround in which Michael thaws, develops manners and completes the journey from errant child to surrogate son. He continues to be abrasive and Noah remains long-suffering, but a relationship of sorts founded on mutual respect takes shape when Noah starts making inquiries into his mother's wartime exploits.

At this point, Donoghue weaves into her narrative a welcome streak of mystery. We hear about Pere Sonne, Noah's famous photographer grandfather, whose prized work Noah's father smuggled to safety when the Nazis invaded France. We learn how Noah's mother sent her son to America two years later while she stayed behind in her occupied homeland. The question is why? Noah searches for the truth and, simultaneously, fears it. Did his mother have a secret lover? Was she a traitor who collaborated with the enemy? If she was innocent and on the right side of history, why did she flee France the minute the war was over?

Thanks to this riddle which pervades the novel, and the double act that powers it, proceedings are deeply absorbing and incredibly poignant. That said, it is hard not to harbour doubts at the outset. It takes Donoghue a while to get going: 100 pages in, her characters are up in the air, still to touch down in France. And as Noah and Michael start flaunting their differences and testing each other's limits, we wonder quite how heavily Donoghue will rely on that tired old trope of the odd couple.

But once in Nice the novel pulls us in. The characters explore the city and in doing so people and place come vividly alive. When the course of events strays close to resembling a travelogue, Donoghue invigorates things by either adding a dramatic twist to the fact-finding mission or creating another tense encounter or comic exchange for her two leads. In an effective – and affecting – touch, Noah’s dead wife Joan pops up at routine intervals and comments, counsels or delivers caustic asides in his head.

Donoghue has written a rewarding novel about uncovered truths and second chances. It may play out in a “city of transients” but its two main characters stick around long enough to leave their mark.