When once asked by the Royal Society of Literature to provide reading tips for children, Ben Okri responded with an interesting list of dos and don’ts. “Read what you’re not supposed to read,” he urged. “Read for your own liberation and mental freedom.” And hunt around: “There is a secret trail of books meant to inspire and enlighten you. Find that trail.”

The characters in Okri's latest novel, The Freedom Artist, aren't able to heed any of their creator's advice. In their totalitarian society, books are banned and vanishing fast. Mental freedom is curtailed and liberation unimaginable. That "secret trail of books" with the power to inspire does exist, and stretches back to the forbidden cornerstone texts of western civilisation – but locating it turns out to be both an outlandish quest and a life-threatening challenge.

Okri begins with a mournful "overture", which outlines the lay of the land and the way of the world. The state is one big prison that makes inmates of its inhabitants. Speaking out and standing out are crimes. Libraries, bookshops and printing presses have closed down. Verbal communication has withered away and been replaced by grunts, shrugs and facial expressions.

But behind closed doors some brave souls do still talk. Okri introduces a young boy called Mirababa, who is curious to discover what lies beyond the confines of his world. His grandfather is painfully aware that the worst possible offences are “those that questioned the nature of reality”, but he nonetheless encourages Mirababa to venture out, seek answers, and bring back “the elixir of freedom”.

Elsewhere, and also in private, Amalantis has questions of her own for her lover, Karnak. What, she asks, is the meaning of the question "Who is the prisoner?" that she keeps seeing on walls? But as soon as she utters this than there are three knocks at the door. Karnak watches in horror as Amalantis is wordlessly marched out, bundled into a van and driven away.

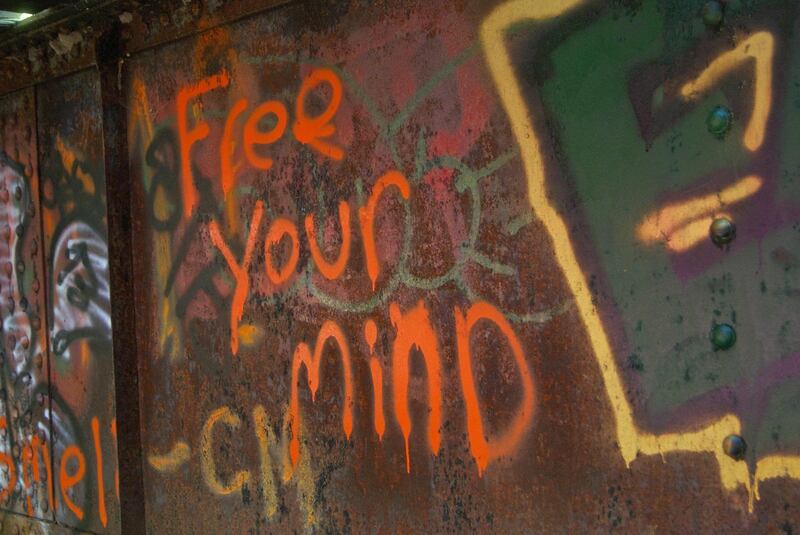

A wave of similar silent arrests spread across the land. But despite the increased police patrols and round-ups the question appears more and more in graffiti and on flyers. Just like Mirababa, Karnak eventually finds himself on a personal clandestine mission to find his missing girlfriend and looking for clues to the identity of the people who disappeared "leaving words and leaflets and mayhem behind".

Following Amalantis's brief introduction and swift departure, the novel is steered for a while by Okri's two male figures. He then brings in a vibrant new female voice. Ruslana is the daughter of a man who set out to safeguard endangered books by turning them into holograms. She now continues his work – "the lost library of the human race" – in what is the last bookshop.

When Karnak pays her a visit, he learns that she awaits that dreaded knock at the door: “Tomorrow I may be dancing with my father in the great darkness.” One day she isn’t there. Was she captured, or did she move one step closer to achieving her goal of joining the underground movement and overthrowing tyranny?

Okri's finest novels are those set in Africa, which fuse his brand of realism with reworked elements of folklore, stories and traditions from his native Nigeria. A dystopian novel branches into new territory that could easily have been shaky ground. Fortunately, Okri is in full control, impressing with a tale that manages to be chilling and moving.

Inevitably there are echoes of Orwell. The shadowy yet omnipotent Hierarchy rules with an iron fist, controlling minds, crushing dissent and rewriting history. A violent clampdown during the age of anxiety gives way to an enforced dumbing-down in the age of equality: ignorance, Karnak learns, is genius. Those who crack up are taken to Houses of Renormalisation. Those who read, revolt or ask too many questions are then devoured by state jackals or thrown into the Prison.

Not that the novel is entirely derivative. Okri’s nightmarish vision contains more than enough original components. He routinely blends in dark magic, mad dreamscapes and surreal fables. Characters trade riddles and aphorisms. The prose is cryptically symbolic and richly poetic. Some of the mystical elements are sluggishly dense and stubbornly opaque and go nowhere; other airier flights of fancy take off and soar. All unfold through a series of short, sharp chapters, perfectly sized to deliver a shock and leave an impression on the reader.

Towards the end, we start to discern a flicker of hope as a sleepwalking populace finally decides to "upwake" and retaliate. "Grow wherever life puts you down," Okri wrote in his Booker Prize-winning The Famished Road.

When the characters in The Freedom Artist do just that, a cerebral novel turns into one with heart and soul.