When the Egyptian millionaire businessman Shafik Gabr was a child, his art teacher told him he was hopeless at drawing.

The young Gabr wasn't just uninterested in art. Now he suspects he might even have "mistreated" the few paintings his parents had on the walls of their Cairo home. It took a journey to Luxor, laden down with photographic equipment, for the penny to drop, setting Gabr on a journey through Orientalist painting that has made him one of the most important collectors of the form in the world. This week, a new book exploring his passion, Masterpieces of Orientalist Art, will be launched in London.

"The play of light in Luxor is amazing," he says of that first photographic expedition. "And I slowly began to realise that I was taking the same images of temples and so on that the Orientalist painters had depicted in the 19th century."

So Gabr started going to museums to see the work of Gustav Bauernfeind, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Eugène Delacroix, all of whom had travelled to the Middle East and North Africa to paint. In 1993, Gabr was ready to make his first purchase, Ludwig Deutsch's Egyptian Priest Entering a Temple (1892), at auction in Paris for US$3,940 (Dh14,470). Almost 20 years and 135 paintings later – "actually, there's another seven now that aren't in the book," he beams – a passing interest has become something of an obsession.

"It's not like these painters were able to get on a plane from Heathrow," he says. "Their journey would take them up to two months, and they would have to carry their own canvases, paint and brushes because they didn't know what equipment they would find when they got to the Middle East."

But how they behaved when they arrived, Gabr believes, sets a striking example for the modern age.

"Frederick Lewis set up a studio in Cairo and dressed in Egyptian garb. He walked the streets, sat in the cafes, tried to learn Arabic. Then he went to Sinai, lived with the Bedu, hunted with them and started painting. These were artists who wanted to engage. That's why I call them early globalists."

Nevertheless, the term "Orientalism" still conjures up some negative connotations surrounding Western colonialism and the exoticisation of people and places in the Middle East, a state of affairs most famously discussed in Edward Said's influential book on the subject.

"I think we should look at them more positively. Orientalist painters didn't go to colonise or occupy," says Gabr. "They went to observe and record. In the book, we see that the Ottoman viceroy Muhammad Ali actually invited artists such as Pascal Coste to modernise the view of his country. So I like to make the distinction between the traveller artists and the 'armchair' painters who sat in Rome and painted Egypt, having never actually been there."

Gabr believes the positive repercussions of the Orientalists' journeys are a template for how the Middle East, Europe and United States might engage with one another today. To that end, in tandem with the book launch next week, he's presenting a new initiative to encourage and sponsor exchange programmes among young Middle Eastern and Western leaders in arts, science, sports, media and business called "East-West: The Art of Dialogue".

"The Orientalists were able to communicate a positive image of the West while they were visiting, and then to the West of what they saw. That is what we're missing today. There's a huge gap in understanding. You ask anyone in the West today what comes into their mind when they hear the words Middle East and unfortunately the first thing will probably be terrorism and radical fundamentalism. You ask the reverse in the Middle East about the US, and it's occupation, conflict, war. My hope with this exchange programme is that we get young Americans, young British people, young Egyptians to sit together with their counterparts so that they can understand each other's lives. This, to me, is critical for the years to come."

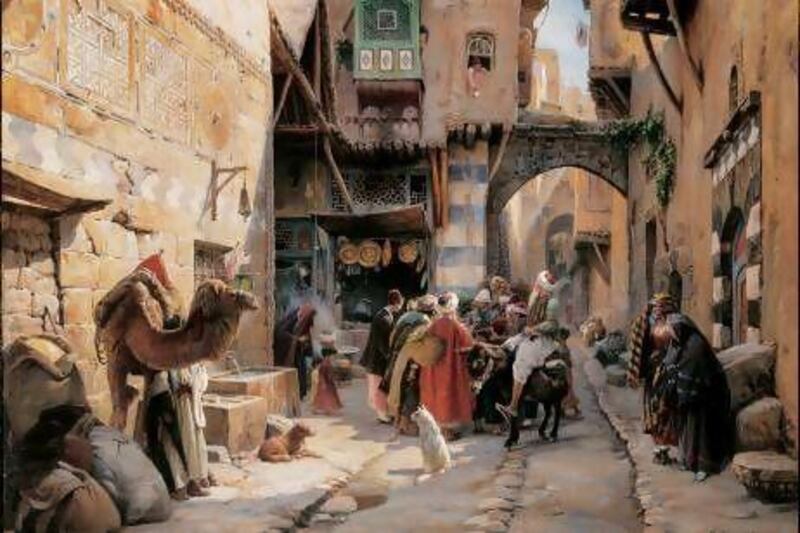

Is it overly tenuous to connect a 19th-century painting of a Damascus street scene to the possibility of resolving international conflicts and cultural misunderstandings? Gabr, refreshingly, doesn't think so.

"Just look," he says, gesturing towards a painting by Gustav Bauernfeind. "Look closely, and he's actually in the painting. He's trying to talk to the people around him, and of course as a German painter he is fascinating them, too," says Gabr. "That's communication - that's how he comes away with a great painting. But are we focusing on communication today? I worry that we are not."

Masterpieces of Orientalist Art: The Shafik Gabr Collection is out on November 15. Find out more about The Art Of Dialogue at www.eastwestdialogue.org