If there's a more vivid starting point for an award-winning debut novel, we're yet to read it. Onjali Rauf was in hospital, after surgery for endometriosis left her fighting for her life. "There was a point when I didn't think I'd be here, and in many ways I didn't want to be," she says. "I didn't think the pain was worth surviving through. But on my third day post-surgery, the title The Boy at the Back of the Class popped into my head and wouldn't leave me alone. I genuinely don't think the book would have been born had it not been for that scary and painful time in my life."

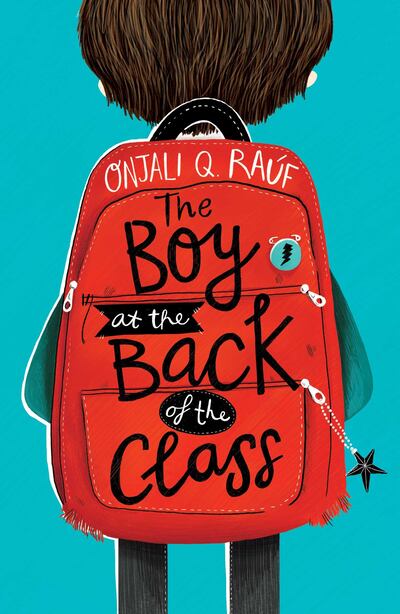

Onjali Q Rauf's debut novel

As soon as Rauf, a British anti-trafficking campaigner, could sit up, she started writing. Her novel, which is about Syrian refugee Ahmet, nine, and a school class in England that comes up with a plan to help him, was completed within two months. In March, it won the Waterstones Children's Book Prize and the 2019 Blue Peter Book Award for Best Story, while it was also in the running for another award, the Jhalak Prize, earlier this month, competing with titles such as Aminatta Forna's Happiness and Guy Gunaratne's In Our Mad and Furious City. That award seeks out "the best books by British / British resident BAME [black, Asian and minority ethnic] writers" and, while Gunaratne won, Rauf's book certainly struck a chord with judges.

"It's surreal to receive praise and awards, but I think the subject matter is something both children and adults harbour a lot of unanswered – and perhaps even embarrassing – questions about," says Rauf.

“The ‘refugee crisis’ is like an invisible constant all around us, comprised of the refugee figure as a strange ‘bogeyman’ – the dehumanised figure to be scared or suspicious of, as if they aren’t really victims or survivors at all but wilful criminals coming to snatch at something they have no right to.

"The book is very much a deliberate backlash against the ongoing belittling of human beings who are in inhumane situations through no fault of their own, whether that belittling is orchestrated by the media or by politicians or by outright racists."

Rauf's dedication to Raehan

Rauf understands better than most the difficulties faced by refugees, as her novel is effectively a response to what she experienced while working in camps in Calais and Dunkirk. It is dedicated to Raehan, "the baby of Calais", whose mother Rauf got to know during her time there. The writer lost touch with her when French police demolished the campsite in 2016.

"It's gut-wrenching losing track of souls you fall in love with, such as little Raehan and his beautiful family," she says.

"And it does make me question the world and its workings and why things have to be the way they are. But the emotions are always mixed and varied with every trip we take. For example in February we were allowed to play for half a day with children aged from three to about 12.

"Hearing them giggling and being shown around the tunnels they’d turned into their makeshift playgrounds was both wonderful and painful.”

A book brimming with kindness

Rauf says she finds the journey home difficult; she's weighed down by guilt and the realisation of how straightforward it is to cross borders with a British passport. "None of it makes sense to me, but the hope lies in those moments of relief or happiness and instances of friendship I see unfolding in the camps," she says. "Without the hope that our collective humanity is bigger than the wars and political games being played, I don't think anyone working in these camps would be able to go on for very long."

Her hope in humanity is the driving force behind The Boy at the Back of the Class. It's a book brimming with kindness and underlines how children aren't born feeling fearful or antagonistic towards people who do not look like them or are from a different ethnic background.

The actions of Ahmet's friends are as powerful a message as his own heart-rending tale. "I think all children are astute when someone in need is in their midst, and they have a natural propensity towards friendly curiosity and helping if they can, in ways grown-ups become too cynical to do," she says. "I wanted to write about children with a capacity to change a world for the better, through acts of kindness big and small. Offering friendship that is empathetic and deeply well-meaning is one of the most powerful things they do. I love the group's innocence and their questioning of the adult world around them."

An inspiration to children

Any questions about how effective a children's book about refugees can be in terms of delivering change are answered by Rauf's growing audience, who have mobilised themselves and are taking action in remarkable ways. Children in Britain have set up crowdfunding pages to make sure every school in their area has a copy of the book, and they have also given letters to Rauf to pass on to refugees and have written to UK Prime Minister Theresa May demanding that refugee children are allowed into the country.

"It's a testament to them that they've seen an opportunity for positive change through the book and taken it; what these children are doing tops every hope I had for the book," says Rauf.

That includes the hope that writing about Ahmet would help Rauf recover her health, while offering her something to focus on other than the pain she felt in hospital. "I began travelling to the camps thinking I was helping the refugees there, when really they're the ones who helped me confront that dark time of my life," she says. "In the acknowledgements, I wrote that there is more love for refugees than they can imagine, both in the UK and in the camps.

"It's a natural instinct to want to help someone in need – you have to deliberately shut that part of yourself down and consciously turn your back to deny someone help.

"If the book can convey to only one single person the amazing power of friendship and how it can break down every barrier, that would be a dream come true."