When the chairman of a literary judging panel expresses relief that the longlisted books are "Nazi-free", there's a temptation to retort: "Well, you'd hope so." But the economist, journalist and broadcaster Evan Davis was making a more nuanced point when the books in the running for the BBC Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction 2010 were announced back in April. In the past, British non-fiction as a whole - and to a certain extent this prize - has been pockmarked with authors continually writing about the Second World War. So when the longlist was narrowed down to six books, in preparation for the awards ceremony in London later this week, the intention was clear: the Samuel Johnson Prize is moving on.

Now in its 12th year, it has become a globe-trotting, internationally-relevant event with a wonderfully diverse outlook. There are books set in North Korea and Wall Street as well as the Arcadian lanes of England. There are investigations into cooking and mathematics. Traditionalists don't miss out - there is also a meaty biography on Charles II - but there is a very real sense that the prize is mirroring a more general public thirst for interesting, quirky non-fiction which doesn't simply tell straight histories of famous people or events.

Admittedly, Jenny Uglow's A Gambling Man: Charles II And The Restoration is marginally the favourite - and not just because of its title. It's a masterful look at a specific period of the English king's reign in the 1660s, when he was fascinated by science, philosophy, and women, at a time when London was recovering from the puritanism of Cromwell. But it is testament to the breadth of the prize that hard on the heels of Uglow's book is a memoir about fishing, which somehow manages to tie in growing up, the heroes in a young man's life and his experiences at a prestigious private school.

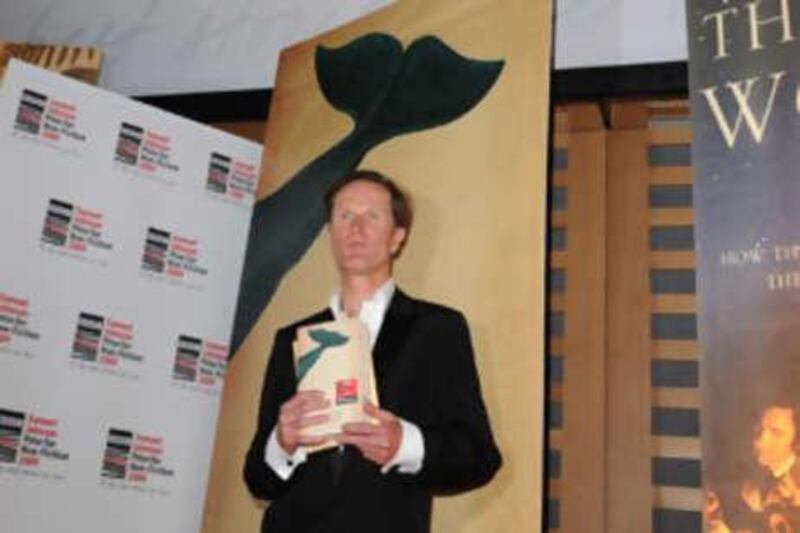

Luke Jennings's Blood Knots is a wonderful book well worthy of its shortlisting, full of beauty and grit. And seeing as last year's prize was won by a book ostensibly about whales (Philip Hoare's superb Leviathan), it would be rather neat if the watery theme continued. The connections are apposite, thinks Jennings, when I speak to him on the eve of the awards. Both Leviathan and Blood Knots are more than geeky studies of whales or angling, they're life journeys, full of enjoyable but always relevant digressions.

Such constant gear shifts - within a few pages we've moved from a particularly satisfying fishing expedition to the revelation that Jennings worked on a farm where the poet Laurie Lee had an affair - are expertly handled, but how easy are they to write? "Well, if you have a passion for something it touches all the parts of your life," he says. "And that's why it's not difficult to write a book like this.You're never struggling to make connections with fishing in everything you write because it's never a separate, discreet activity. If you read Nick Hornby's Fever Pitch, for example, of course he's interested in football but every area of his life feeds his passion. "The best non-fiction books don't have to tortuously strive to make such connections, because they are already there. And that kind of passion is interesting and moving to read about whether the writer is famous or not, because we all like to know what drives people."

But it certainly helps the propulsive, entertaining nature of Blood Knots that its author has written fiction in the past. Of Jennings' three novels, Atlantic was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1996. He's also the dance critic for The Observer, and has written a guide to ballet. So he's uniquely placed on this shortlist to understand how fiction and non-fiction merge and dove-tail. "The main difference in writing a book like Blood Knots is that I knew the story straight away, because it's my own," he laughs. "Fiction can be a bit more tricky than that. I love fiction and of course I write fiction, so I'm not going to make the case against it, but non-fiction can be emotional, telling and cut to the heart just like anything else."

This idea - that non-fiction can have an emotional resonance which elevates it beyond mere "show and tell" - comes to the fore in another shortlisted book, Nothing to Envy: Real Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick. She is the LA Times foreign correspondent and could easily have written a straightforward exposé of life in North Korea's most accessible city, Pyongyang, but instead there are heartbreaking stories about six defectors from the north-eastern city of Chongjin.

Particularly poignant is the tale of two young lovers who didn't dare tell the other that they were thinking of defecting because of the potential for reprisals. Jennings' book, too, is at its most telling when it describes his father's act of heroism in - whisper it to Evan Davis - the Second World War. Of course, trying to spuriously find connections between all the books on the shortlist would be a tortuous exercise. Jennings says himself that "it's an incredibly broad sweep of subject matter, and I don't think any of them have really got anything in common."

He's wrong in one sense: they do all tell entertaining stories. Alex Bellos' Adventures In Numberland is essentially an accessible delve into what mathematics means in everyday life, stylistically closer to a travelogue than a text book. Inside The Battle To Save Wall Street, by Andrew Ross Sorkin, is an incredibly gripping portrait of the people in the middle of the credit crunch, rather than simply a retelling of what happened.

Rounding off the shortlist, Richard Wrangham's Catching Fire is a book by a primatologist first and writer second, but his theory that cooking food rather than eating it raw is what made us human is compelling stuff. It is often said that a greater truth is found in fiction: in the past year Hilary Mantel's historical novel Wolf Hall, with its focus on Thomas Cromwell, has dominated book charts and awards. So judging by the shortlisted books, I wonder whether Jennings feels the opposite holds true too, that there's actually the opportunity for greater storytelling in non-fiction.

"Well, the best stories are true, aren't they," he says. "And memoir in particular is interesting, because unless there's an agenda there they have an honesty to them. There's a 'what the hell' quality, because you strive for the truth and the patterns in your life. That process is revealing to both the writer and the reader I think, because the gloves are off!" And what patterns did he find? "Well, I first decided to write a book about fishing because I've always felt that it was a way to talk about the more profound issues and elements of a life story.

"Angling is in a sense a metaphorical activity, in that you're searching - blind - in an impenetrable dimension. For me, that's a little like looking at my own past, too. I can't go back, but by writing about it I can at least shape it into something emotionally coherent." He hopes the judges will agree on Thursday. But whichever book they choose, they'll certainly concur with Jennings on one point; that all the best stories are true. It is, after all, also the official subtitle of this quite wonderful, globe-spanning prize.

The BBC Samuel Johnson Prize For Non-Fiction is announced on July 1. For more information visit www.thesamueljohnsonprize.co.uk