Mo´ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove

Ahmir 'Questlove' Thompson

Grand Central Publishing

Turn Around Bright Eyes: The Rituals of Love and Karaoke

Rob Sheffield

It Books

Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre

Ethan Mordden

OUP USA

Music geeks speak a language all their own, one proudly attuned to their own highly technical concerns and little else.

"Motown wouldn't commit to one factory plant - they used 20 plants regionally - and that was very troubling for me, as a kid, because it resulted in inconsistent ink quality."

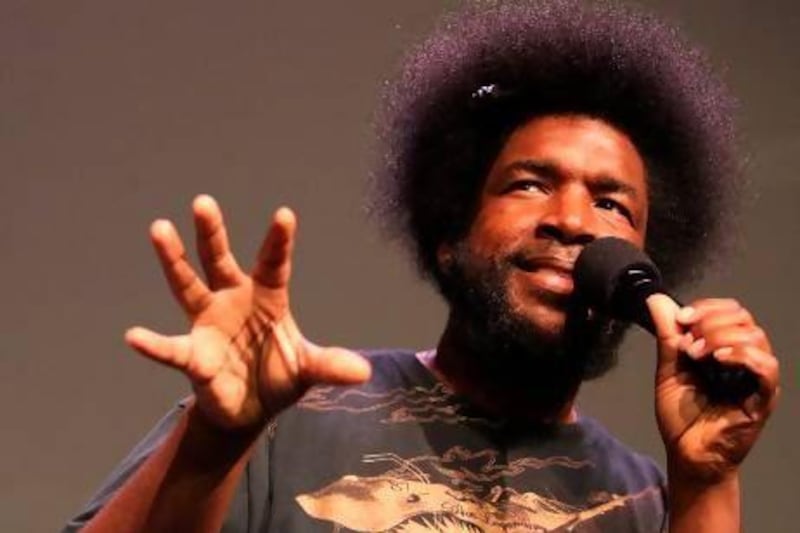

Perhaps Questlove, bandleader and drummer for the acclaimed hip-hop group The Roots, is poking fun at his own youthful musical exuberance, or perhaps his co- writer Ben Greenman is mocking the soul-music fanaticism of his famous collaborator.

But the evidence, copiously compiled in Questlove's memoir-cum-music-appreciation seminar, Mo' Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove, indicates otherwise.

Questlove lays out and pens mock Rolling Stone reviews for each of his albums before their release; he attempts to dazzle R&B singer D'Angelo at a Roots show by slipping an obscure Prince riff into a number; on being introduced to Prince, his youthful musical idol, he promptly declares that "Dinner with Delores has the greatest ending in postmodern black rock history."

Modelled on, and hoping to catch some of the tailwind of, Jay Z's memoir Decoded, Mo' Meta Blues lives up to its title with a clever and, at times, cumbrous structure. Questlove is shadowed by the band's co-manager, Richard Nichols, who fleshes out sketchy passages, corrects mistaken memories, and adds a touch of industry vinegar to what begins as a fan's gushing.

Greenman, too, chimes in in his own voice, with a series of emails to the book's editor, detailing his concerns with the project: "I wouldn't necessarily say that the book is coming into better focus, though I would say that my excitement over the nature of the blurriness is increasing."

The postmodern hoo-ha is deftly executed, but ultimately of secondary interest to Questlove's self-portrait of a youthful music nerd losing, and then finding, himself in the music.

He estimates that he purchased approximately eight copies of Prince's 1999 after his strict parents kept confiscating them, and once broke a salad bowl to keep them from hearing the erotic interlude as Lady Cab Driver played on the radio. (Mo' Meta Blues is as much a love letter to Prince as a memoir, and I haven't even mentioned the time Questlove went roller skating with the Purple One and Eddie Murphy.)

"My strength as a DJ lies in masterful segues," Questlove modestly tells us.

Rob Sheffield's strength, in his music memoir Turn Around Bright Eyes: The Rituals of Love and Karaoke, does not lie in masterful segues. Asides about Rod Stewart and Rush and the peculiarities of Irishmen litter the text indiscriminately.

Even the main thrust of the book, about the allure of wielding a microphone before a roomful of drunken strangers, sags at times, already familiar from books like Brian Raftery's Don't Stop Believin'.

Turn Around is better as a memoir than music journalism, its strength the story of a sad, not-so-young man - Sheffield's wife died unexpectedly when they were in their early 30s - rediscovering his zest for life.

"At an age when many of my friends felt their lives were just beginning, I felt mine was over," he writes.

Karaoke unexpectedly calls Sheffield back to life, and to falling in love again. "Sometimes you can feel like you're experiencing some of the most honest, intimate moments of your life while butchering a Hall & Oates song at 2am in a room full of strangers," he wryly observes.

Karaoke has even gone so far, Sheffield notes, as to replace the slow clap as a one-size-fits-all cinematic trope.

Even while veering away from his professed point, Sheffield can be quite funny, as when he muses on what the emergency-room doctors might say about a deep thigh bruise he suffered while zealously banging a tambourine at rock-music camp: "He rocked too hard. He'll never come back."

Music is an ever-flexible metaphor for life, its waxing and waning, crescendo and decrescendo an apt symbol for our triumphs and tragedies. "The longer you stay married, the more you have to give up on the idea of perfection. And the more you probably relate to rock stars with long and tattered discographies, people like Smokey Robinson or The Kinks or Neil Young who make a hundred messy records rather than a few perfect jewels."

Sheffield is healed, but not whole, and his messy book stands in for his charmingly messy soul: "I am a 'do it all at once' kind of guy. I am not a 'do it today, then start over from scratch and do it again tomorrow' kind of guy. I get flustered at tasks I am unable to complete, which is almost all of them. Things like grief and love and mourning."

The American musical theatre, in its earliest form, was single-mindedly devoted to the banishment of matters like grief and mourning, and to the celebration of daffy, breezy love above all.

Ethan Mordden's Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre is a double-time march through 300 years of musical joy, from John Gay's The Beggar's Opera to The Book of Mormon.

The arc of Anything Goes takes us from the frothy charm of Jerome Kern-Guy Bolton-PG Wodehouse musicals to the more psychologically astute, character-based work of Rodgers and Hammerstein. Where once George M Cohan had "stopped just short of running the candy counter" at his star-vehicle spectacles, the new, adult musical demanded "unique characters whose interaction creates unique stories." The musical had once been fancy-free pleasure; now, after the Second World War, "everything in the musical is starting to become difficult". Anything Goes hinges on the midcentury glow of musical majesty. Shows like Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, and Guys and Dolls articulate a homegrown American seriousness and candour and humour that sever the musical from its bawdy, deliberately forgettable roots.

Mordden has obviously mastered his material, and summons some wonderful titbits to enliven his narrative. The squad of police officers "pouring down the aisle" during a performance of Florenz Ziegfeld's Follies of 1907, pretending to raid the theatre, "only to leap onto the stage and join Salome in a cancan," or the "blackened teeth and Mammy Yokum pipe" donned by Bette Davis for a musical number in her ill-fated revue Two's Company, beautifully convey the simultaneous spectacle and silliness of American theatre in its heyday.

Mordden also expertly synthesises his enumeration of artistic styles and performers with considerations of the effect of design and technology, like changing set-decor techniques and the increasing use of body microphones.

Gypsy's success stemmed in part from its adopting brass-heavy orchestration, replacing the strings-dominated sound of earlier shows.

Emerging a few years after Larry Stempel's capacious, wise Showtime, Anything Goes cannot help but feel slightly rushed in comparison. Anything Goes loses focus after the 1970s heyday of Stephen Sondheim (although Mordden is surprisingly sympathetic to the 1980s megamusical exemplified by The Phantom of the Opera), perhaps because Mordden himself does not find much to attract his interest in the past three decades' musicals.

Why does Avenue Q appear and disappear in a sentence, and The Book of Mormon hardly register? Mordden knows so much that we occasionally wish he would pause momentarily to share a bit more with us. The chatty interjections studded here and there in the book—"Impasse!"—do little for Anything Goes's sense of authority, or its entertainment value.

"The carefree musical comedy is no longer functional," Mordden tell us, but the magic of the theatre endures. "A character requires something to complete his or her existence, and, in confiding in us, draws us sympathetically into his narrative." Anything Goes draws us sympathetically into the musical's own efforts to define itself, and leaves us to wonder: is it now complete?

Saul Austerlitz is a frequent contributor to The Review.