Like comic books, or baseball cards, vinyl albums are both physical objects and the subjects of a spiritual yearning. They are entirely utilitarian - place them on the turntable, drop the needle - and representatives of a lost republic of desire and loss. "That's how come I have to be an atheist, Rolando, seeing all this fine vinyl the poor man had to leave behind," Archy Stallings murmurs at the outset of Michael Chabon's new novel, Telegraph Avenue, while flipping through a dead man's record collection. "What kind of heaven is that, you can't have your records?"

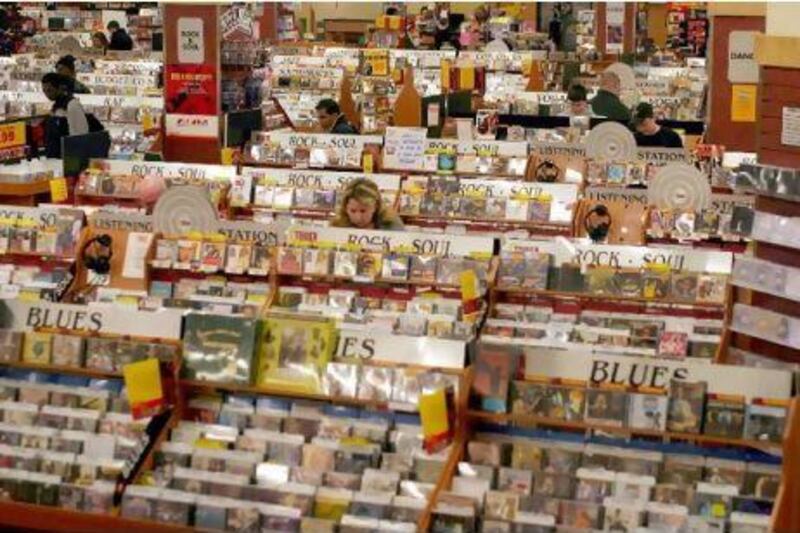

Having written masterfully about comic books, and the men who created them, in his Pulitzer-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Chabon has now moved on to that other primal totem of obsessiveness and possessiveness. Archy and his partner, Nat Jaffe, run Brokeland Records, a gathering place for vinyl junkies and obsessives of all stripes to congregate. Distracted and indifferent, cheating and dissembling, Archy is threatening his future with his wife Gwen, even as he plans for impending fatherhood. Gwen works as a midwife alongside Nat's wife Aviva, and their union, too, comes under fire when a home birth goes disastrously wrong. Nat's son Julius, called Julie, enamoured of Quentin Tarantino films, comic books and eight-tracks, is powerfully attracted to Titus, a teenage boy he encounters in a continuing education class on Kill Bill. Titus, as it turns out, is not only Julie's crush, but Archy's son, forgotten and abandoned to the fates.

Telegraph Avenue is composed of these intricately interwoven relationships: partners and lovers, fathers and sons, cool-headed planners and hot-tempered ranters, African-Americans and Jews. Chabon's novel is about the consolations of masculinity, where sadness and guilt are transmuted, by some invisible force, into arguments over the relative condition of a copy of John Coltrane's Kulu Sé Mama. Archy and Nat are wearing out the grooves in their own relationship, their partnership possibly scratched beyond repair by the stresses of financial indignity and the digital iTunes future threatening to wipe out their business. "Most of all," Chabon says of Archy, "he was tired of being a holdout, a sole survivor, the last coconut hanging on the last palm tree on the last little atoll in the path of the great wave of late-modern capitalism waiting to be hammered flat."

Archy, wayward son and absentee father, is in danger of losing everything: his beloved store, his wife, his unborn son and the son he forgot he had. He is also about to bury the closest thing he had to a genuine father: that master of the Hammond B-3 organ, Cochise Jones. "Only Mr Jones," he feels, "had always stopped to drop a needle in the long, inward-spiralling groove that encoded Archy and listen to the vibrations." Cochise had once told Archy that a "good heart is 85 per cent of everything in life" and yet Archy's good heart seems too skimpy to offer any comfort to those in need of his ministrations. The records become the substitute for lost time, for emotions once white-hot and now encased in a sheath of black wax. "They were worth only what you would pay for them," observes another dealer in nostalgia, "what small piece of everything you had ever lost that, you might come to believe, they would restore to you."

Nostalgia has seeped into the bones of Telegraph Avenue, with everyone craving a return to a bygone moment when the broken world was whole - or at least less shattered.

Archy's father Luther rhapsodises about "the freest men that ever lived", the Pullman porters who used their jobs on the train to build a middle-class life in Oakland, "armoured in smiles". The dream of the Pullman line has curdled into the aptly named Brokeland, emblem of a world damaged beyond repair. Adulthood, according to Chabon, begins with acknowledging your own starring role in the process of demolition. Archy, looking forlornly at Titus' "new white socks on their plastic bopeeps" discerns the first stirrings of embarrassment at his many failures: "It was when he looked at his son and pictured the underpants and socks that he first felt truly ashamed. This boy had no one in the world to ensure, to at least check from time to time, that his underwear was clean."

Telegraph Avenue is hungry for a bygone era - not just the time when pristine copies of Kulu Sé Mama rolled off factory lines and into the overstuffed bins of mum-and-pop stores across the country but when the wizards who created the masterpieces were in their first bloom. "Black music is innovation," begins one pivotal, profanity-laden Chabonian riff, granted to the ex-football star turned entrepreneur Gibson Goode, whose megastore threatens Archy and Nat's very existence. "But face it, I mean, a lot has been lost. A whole lot. Ellington, Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, we got nobody of that calibre even hinted at in black music nowadays. I'm talking about genius, composers, know what I'm saying? … Guitar, saxophone, bass drums, we used to own those m************. Trumpet! We were the landlords, white players had to rent that s*** from us."

Perhaps here is the place to lift the needle from its groove, stop the music and address the 800-pound saxophonist in the room, lingering dangerously close to the box of rare-groove 45s and original Blue Notes. In his two best-loved novels, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay and The Yiddish Policemen's Union, along with such lesser efforts as The Final Solution and Gentlemen of the Road, Chabon had been scratching Jewish history, past and present, real and imagined, like a DJ working a killer break from a record whose label had been strategically defaced. Both Chabon and his characters were creatively remixing the past, transmuting the horrors of Nazism into a superhero who might symbolically undo the Holocaust, or transplanting the Jewish homeland from the Middle East to the frozen north of Alaska.

But here Chabon is illicitly remixing someone else's track, getting his fingers sticky with others' cultural detritus. There will inevitably be some who will accuse Chabon of some form of neo-minstrelsy, of violating the unwritten code of interracial propriety by adopting a voice not his own. He is, as Chabon himself describes one of his characters, "some Jewish dude trying to think like an ass-kicking soul sister" - or perhaps soul brother.

Eliding the desire to point to the rich American tradition of speaking in others' tongues - of Twain, Melville, DeLillo and, above all, Tarantino, who haunts Telegraph Avenue like a secret sharer - let us instead skip ahead to Chabon's best defence: he is too good not to do it.

Telling a story is always a matter of imitating someone else's sound, be it your best friend, the guy standing outside the bodega, or your favourite writer. Chabon is imagining himself into the mostly African-American world of bedraggled, beautiful Oakland, his empathy generous enough to encompass an entire universe of crippled souls yearning for wholeness. It is what novelists do. To miss this is to condemn every author to an eternity of half-masked memoirs.

"Creole, that's, to me, it sums it up," Archy offers in his eulogy for Mr Jones. "That means you stop drawing those lines. It means Africa and Europe cooked up in the same skillet. Chopin, hymns, Irish music, polyrhythms, talking drums. And people." Archy later calls it "Brokeland Creole" and Telegraph Avenue is written in that same generous American vernacular, composed of half-forgotten riffs, chunky solos and elegant rhythms.

Chabon grants one of the most transporting melodies, at novel's end, to Gwen, who sums up both the book's aura of bittersweet resignation to melancholy and responsibility, and its surprising reach across barriers of time and ethnicity: "One day the feeling might come to resemble forgiveness but, for now, it was only pity, for Archy, for his father and his sons, for all the men of whom he was the heir or the testator, from the Middle Passage, to the sleeper cars of the Union Pacific, to the seat of a fixie back-alleying down Telegraph Avenue in the middle of the night." We are, all of us, the inheritors of history. It belongs to each of us, equally, and we portion out to ourselves whatever melody assists us in finding the music of our own lives. Chabon has done so, triumphantly, without embarrassment or apology.

Saul Austerlitz is a regular contributor to The Review.