Twenty years ago, in A Vain Conceit, his book about British fiction in the 1980s, the writer DJ Taylor noted that "critics impose long sentences of immaturity on young writers in Britain". As an example Taylor gave Martin Amis, who by this point - 1989 - had been writing novels for the best part of 15 years. He was a 40-year-old man who at just 35 had produced Money, one of the defining novels of the decade. But still, said Taylor, there was a suspicion of "a callow youngster, a talent developing in minute skips and hops which will one day 'mature' and produce something 'significant'".

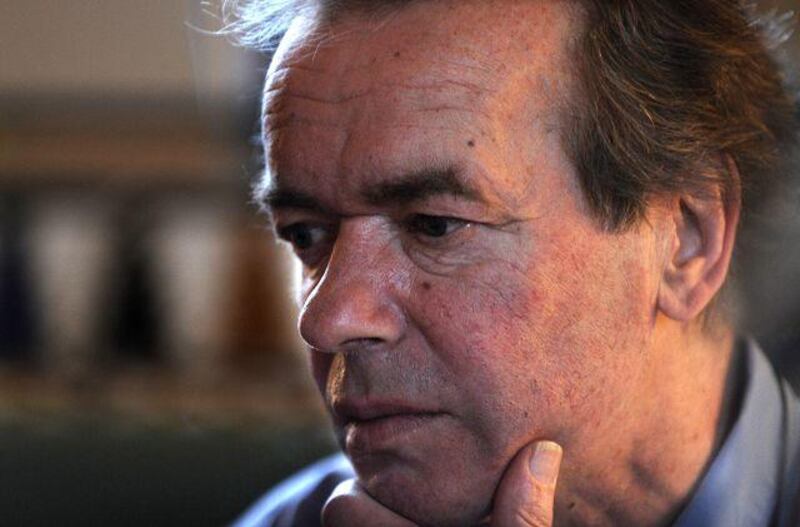

Incredibly, this suspicion persists, even though Martin Amis will turn 60 next Tuesday - surely the oldest enfant terrible in town? We're not ready to think of Amis as an old man, perhaps because he has existed for so long in our imaginations as somebody's son - and not just anybody's son: that self-styled old buffer Kingsley Amis's. Sixty isn't really old, of course. But it is a decent vantage point from which to look back on all that Martin Amis has achieved since he burst onto the literary scene in 1973 with The Rachel Papers - and forwards, towards an uncertain future.

For this once-lauded writer's stock is not at its highest right now. Indeed, the consensus among critics is that there has been a tailing off in the quality of his work since his justifiably praised memoir Experience was published in 2000. His new novel, The Pregnant Widow, was originally scheduled for 2008, but its fraught gestation means it won't be released until early next year. We know little about it except that part of it is set in the early 1970s in a castle in Italy. Amis has promised that it will be "blindingly autobiographical" and the early buzz, at least, is positive. But even ardent flame-keepers are managing their expectations.

How did it come to this? Not so long ago, Martin Amis was the golden boy who could do no wrong. Every young male writer wanted to be him, or at least to write like him; to possess that incredible linguistic facility. (Consider the description of New York police cars in Money: "pigs cocked traps ready for the first incautious paw.") From his father, the author of Lucky Jim, he had inherited satirical brio and a bilious, Swiftian comic energy. But where Kingsley had always scorned the modern world, Martin embraced it: like John Self, the obnoxious anti-hero of Money, he was "addicted to the twentieth century".

Amis's first novel, The Rachel Papers, was published when he was just 24 and working at the Times Literary Supplement. The acclaim was fierce and grew louder over the next 10 years. At first he shrugged it off: "Everything that's written about you is actually secondary showbiz nonsense, and you shouldn't take any notice of it," he told an interviewer in 1984. But this must have become increasingly difficult as the manufactured controversies piled up. When, in 1994, he left his long-time agent, the late Pat Kavanagh, and signed up with Andrew "The Jackal" Wylie, allegedly because he needed a large advance for his new novel The Information to pay for urgent work on his rickety teeth, the story ran and ran: Kavanagh was married to one of Amis's best friends, the novelist Julian Barnes, who promptly excommunicated him. (The pair have since patched things up.)

In retrospect, signs that Amis was starting to mistrust what evidently came so easily to him - his way with a comic sentence - were visible as early as 1987's Einstein's Monsters. A mixed bag of short stories linked by the theme of Amis's fear of nuclear weapons, it felt like the work of someone casting around for a big subject, finding it, but then taking a line that merged so seamlessly with the consensus that it wasn't clear what was being added to the debate. He bounced back with the darkly comic urban fable London Fields in 1989, but put his "serious" hat on again for 1991's Time's Arrow - the story of a Nazi doctor told backwards so that he seems to raise gassed Jews from the dead. It was ambitious, but felt glib and tricksy. Still, in The Nature of Evil he believed he had found his subject - no matter how much it wriggled and squirmed in his grasp or how much critics put him in his place by calling him a "comic stylist".

Ah yes, style. Amis has always believed style to be the novelist's pre-eminent concern, once saying: "I would certainly sacrifice any psychological or realistic truth for a phrase, for a paragraph that has a spin on it." He might have added that he would also sacrifice emotional truth: from the start, readers complained that his writing was cold. (As one senior editor at a major publisher put it to me recently: "Philip Roth manages comedy and deep humanity, but for all his brilliant wit and wordplay Amis has never made us care emotionally about his characters in the way that Roth does.")

As the 1990s rumbled on, Amis let it be known that he was looking to America for inspiration. His peers, meanwhile, were gradually eclipsing him in sales terms with novels that viewed emotional truth as the only worthwhile quarry. Ian McEwan's 1987 novel The Child in Time had examined the random disappearance of a child in a supermarket through the prism of time theory. Barnes was exploring the philosophy of love in erudite, form-busting novels like A History of the World in Ten and a Half Chapters. Amis was never terribly interested in plot whereas the book that ushered in the most successful phase of McEwan's career, 1997's Enduring Love, was heavily plot-driven, almost a thriller.

Some younger writers, particularly Will Self and Zadie Smith, acknowledged Amis as a major influence. But a number began to define themselves in opposition to him. Matt Thorne and Nicholas Blincoe's New Puritans project was at the time (2001) seen as explicitly anti-Amis in its insistence on formal simplicity and the reification of the banal, though Thorne now says that his intentions were slightly misconstrued.

"The way I've felt about Amis is not so much that I dislike him but rather that, for me at least, I've never really understood why he exerted such an incredible influence on the generation above me," says Thorne. "Whenever I speak to writers like Geoff Dyer about him, they always suggest I'm trying to be deliberately iconoclastic. But I genuinely believe that most people in their mid-30s and younger know Amis more as a public figure than a novelist."

In 2003 Amis attempted a return to the urban comic novel with Yellow Dog. But its different strands - explicit material, tabloid culture, the royal family - failed to coalesce satisfactorily and it received some of the worst notices of his career. The keynote was struck early on with a review by the novelist Tibor Fischer in the Daily Telegraph which called it "not-knowing-where-to-look bad". I interviewed Amis around this time and although he told me he'd stopped reading his press ("It's a function of ageing: you've got to get on to the next thing and you can't allow your mind to get snagged"), he had been told about the review and was clearly angry and upset: "I don't think novelists should be hired as obvious put-up jobs to have a go at other novelists. To hell with him."

Today, Fischer says he has no regrets about the ferocity of the review. "Why would I regret it? I wasn't trying to upset him, just to say that I thought it was a very bad book. It was disgraceful and substandard. He was hoping his reputation would allow him to coast through it. House of Meetings, the one that came after Yellow Dog, I didn't like either, but at least he was making an effort again.

"It shouldn't be forgotten that Amis is in an immensely privileged position. Random House and his other publishers pay a lot of money for his books. A lot of younger writers can't get published at all nowadays because people like Amis have hogged all the money." One of the problems with Yellow Dog was September 11. Amis told me that its effect on him had been huge; that, like many writers, he had felt dislocated in its aftermath and briefly considered a change in occupation. Gradually his opinions about September 11 and Islamic fundamentalism would crystallise. In a notorious offhand comment to a journalist from The Times, he said: "There's a definite urge - don't you have it? - to say the Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order." No doubt this will be a hot topic when he visits the UAE next year for the 2010 Emirates Airline International Festival of Literature with his wife, the writer Isabel Fonseca.

The sight of Amis defending himself on Britain's Channel Four News was odd. It made you think what a curious and serpentine journey from The Rachel Papers and Money to this. "I think that like another genius, Woody Allen, Amis has got stuck in a rut," says a senior publishing figure. "His main tone is comic, but when he tries to expand his range it somehow doesn't convince." Does Amis still have commercial clout? Experience, his memoir, sold well, subsequent books like the September 11-themed collection The Second Plane less so. But his reputation remains intact - comparable perhaps to that of someone such as David Bowie: he may not have made a decent record for years, but the sum of his achievements is sufficiently great for it not to matter too much. Interestingly, one publisher says he feels about Amis the way he feels about The Rolling Stones: "I was a huge fan when I was younger and still get excited when I hear he has a new book out."

Does that mean, I ask, that he would publish Amis were he to become available? "It would depend on the price. But yes, if we could reach a happy agreement, I'd be thrilled to."