Among journalists covering conflict, there is a constant dividing line between the trailblazers who make it to the front line versus those left behind.

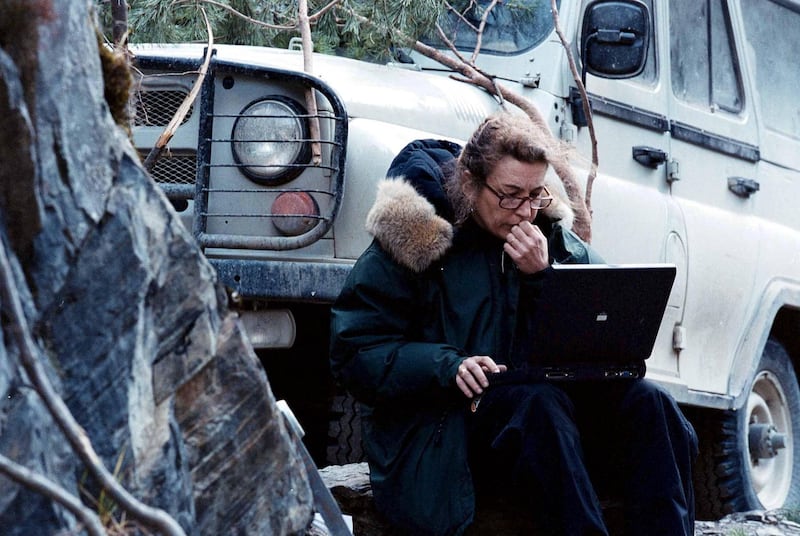

Marie Colvin, an American who made her career covering the Middle East as a foreign correspondent of the United Kingdom's The Sunday Times was almost always on the right side of the line.

Her belief in being there and bearing witness was fatally tested in 2012 when she was targeted by the Syrian regime in the ruins of the Baba Amr siege. She died in a bombardment that hit the rebel-run media centre. Just weeks before, Colvin met the television journalist Lindsey Hilsum in Beirut, where the pair had shared a friendly dinner. As Colvin headed to Homs and Baba Amr, Hilsum wondered why she, too, was not crossing to the front line with her old contemporary.

The trailblazing correspondent of their generation

Hilsum has now written the life of Colvin, In Extremis, released this month, just as Matthew Heineman's biopic starring Rosamund Pike is about to hit cinemas in the United States. It chronicles a remarkable life lived to the full. Colvin was equally at home in a bombed-out crater and the velvet-draped parlour of a royal palace. Her love life, with divorces, reconciliations and a suicide, was just as fraught as the civil wars she covered.

To Hilsum, her colleague was the trailblazing correspondent of their generation. "Once she got into a war zone, she got on with the job. She was no different from the rest of us except that she went in further and stayed longer," Hilsum told The National in an interview in London's Notting Hill, the district from where the American reporter had forged her legend. "She had incredible grit and endurance."

The events of Colvin’s last days remain a riddle. Wael, the young Syrian interpreter who helped Colvin, told Hilsum that he saw the 56-year-old journalist as an “iron woman” well capable of a kilometre and a half through a storm drain three times. But there is still the question of why Covlin, who had filed one story from Baba Amr, returned to the siege knowing the regime was closing in. “It’s a hard one for me to understand. Twice is different from once. To go back in again when you’ve been in already and got a good story. I can’t understand that,” Hilsum says.

Making sense of Colvin’s career, Hilsum points out the parallels with another scoop during the so-called war of the camps in Lebanon in 1986. Colvin and a photographer bribed a commander to allow them to run across no-mans land into the Palestinian Bourj al-Barajneh refugee camp where 15,000 people starved under siege by the Shia militia, The Amal Movement.

"The tragedy is that her death didn't make a difference because her whole belief in journalism was about making a difference. In Bourj al-Barajneh in 1987 she made a difference," says Hilsum. "Gorbachev was backing [former Syrian president] Hafez al Assad, who was backing Amal. The pressure from the reporting in the Sunday Times was too much. Within two days, they'd ended the siege. That sense of 'what I do makes a difference' stayed with Marie all her life."

How she found her way to the Middle East

Colvin was not born to make her name as a Middle East correspondent. The opportunity came her way suddenly after she moved to Paris as a news agency correspondent. “On her 30th birthday, she was writing in her diary how she was fat and ugly and all ‘oh woe is me’,” says Hilsum. “Within a few months, her whole life had changed.”

Two months later, she met David Blundy, another ill-fated Sunday Times correspondent, who was her mentor and recommended her for a job at the paper. Around the same time, she travelled on a press trip to Libya, where she had the first of many encounters with Muammar Qaddafi.

Colvin’s involvement with the Middle East in the 1980s and 1990s was dominated by her strong ties to both Qaddafi and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

“She had long and complicated relationships with Qaddafi and Arafat,” says Hilsum, describing these as a testament to her diligence as a journalist. “She lived through historical times. Arafat really liked her, but that didn’t mean she was soft on him. There was a time when she challenged him about terrorism and as she pushed him, the guards started to cock their weapons.

____________________

Read more:

Matthew Heineman’s new biopic on Marie Colvin is ‘an homage to journalism’

Editorial: Journalists’ protection is vital in getting to the truth

Between the lines: counting the cost of reporting from Syria

____________________

“He got very angry with her and ended the interview. She thought that would be that, but after about six months they were back in touch on the old terms.”

Her mix of charm and durability was on display in Libya in 2011 as she was covering the rebellion against Qaddafi's regime and its eventual downfall. Despite writing about how he had tried to force her to have an HIV test, she maintained access to the autocrat. "The last interview Qaddafi gave was with Marie," says Hilsum.

'I’m uncomfortable about creating the myth of Marie'

Colvin kept a diary and her life story has the feel of a dark fairy tale. Brought up in a large New York family, she made her way to Yale on a path to worldwide renown. Along the way, there was a series of terrible relationship breakdowns and the hangover of battlefield traumas, including the loss of an eye reporting on the Sri Lankan civil war in 2001.

The term "in extremis" comes from a passage Colvin herself wrote about her work in 2001, but Hilsum cannot ignore the tumultuous personal stories, however dazzling the journalism. "I'm uncomfortable about creating the myth of Marie," she says. "Women are written about differently to men. The In Extremis line was about what she was reporting on. Have I fallen into a trap of foregrounding the emotion? That was Marie," she adds. "She was a feminist, but a bit of her was always longing for a long white dress and a picket fence existence."

Exciting to see my new book #InExtremis:the Life of War Correspondent #MarieColvin on sale at Hatchards Piccadilly a few days before official publication. pic.twitter.com/hQsFCOc8Uz

— Lindsey Hilsum (@lindseyhilsum) October 30, 2018

Hilsum describes the Middle East as a story that came “back to her” amid other glories, notably in East Timor as the territory fought for independence from Indonesia.

The build-up and aftermath of the 2003 invasion of Iraq does not hold up well to scrutiny. Colvin was too close to Ahmed Chalabi, the exile who provided that uncertain narrative that underwrote the march to war against Saddam Hussein. “She believed Chalabi. I think Marie’s big weakness as a journalist was believing Chalabi for far too long,” says Hilsum. “It’s hard to understand why she did that. Because access to Qaddafi and Arafat had stood her in such good stead?

“Chalabi had brought very good stories to her,” she adds. “A lot of what he said was true, apart from the bits that weren’t, which is always the case with a plausible fabricator.”

Yet post-Saddam Iraq also provided one of Colvin’s strongest stories. Hilsum writes about how Colvin toured Basra in 2007, the first unembedded western journalist to take the risk of working in the city for two years. The piece describes the plight of women persecuted by the militias and the views of the police chief unable to help them. With her reporting, she challenged the commanding general of British forces in Basra, who was trying to claim that everything was going according to plan.

“When I look at that, it’s not one of her famous stories, but it is one of her best,” says Hilsum. “It shows she was so sensitive to other people’s suffering and I think that’s because she was so confessional and open about her personal suffering.”

In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin is out now