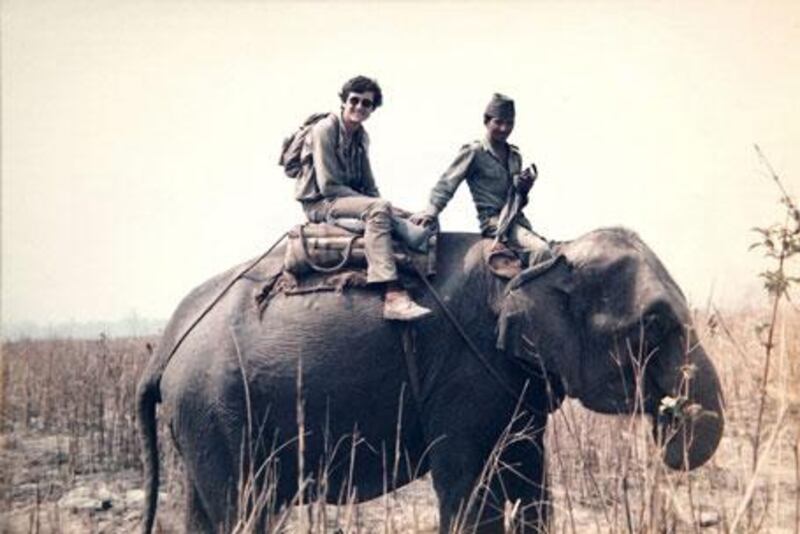

Novelists often have strange inspirations for their books. Tracy Chevalier's Girl With a Pearl Earring was sparked by a 16-year-old poster on her wall. The story of Twilight came to Stephenie Meyer in a dream. But none, surely, are as bizarre as that of English author Christopher Nicholson. "I have this fantasy that I might eventually be able to ride through England on an elephant," he says, somewhat sheepishly. "I've always thought it would be a wonderful thing to do, and it always hangs in my mind. I thought that writing this novel might have killed the fantasy, but if anything it's just made me feel that it might be a little bit more possible."

The brilliance of The Elephant Keeper - Nicholson's second published novel, shortlisted alongside the literary juggernauts Colm Toibin and Hilary Mantel recently in the Costa Book Awards - is that its author makes such a scenario strangely plausible by taking the reader back to the 18th century, when two young elephants are unloaded amid the strange cargo of a ship from the East Indies. Purchased by a benevolent Somerset landowner, Mr Harrington, Jenny and Timothy are taken to a rambling estate in the English countryside and entrusted into the care of a stable boy, Tom. Equal parts fairy tale, social history, love story and commentary on the nature of storytelling, Tom's account of his life and relationship with his giant charges is absorbing, endearing and profound. Jenny becomes a powerful, almost saintly force amid a developing human tragedy. The story is absolutely not, however, Doctor Dolittle for adults.

"I really didn't want it to turn into a twee animal story," Nicholson says. "It's such a danger when you write something that has something as well-loved as an elephant in a novel that you're going to be accused of being highly anthropomorphic, of being soft and sentimental. But the title of the novel isn't The Elephant, it's The Elephant Keeper - which is quite an important distinction. It's really about Tom and the interesting and complicated relationship between a man and a really intelligent animal like an elephant."

It's also about the strange hierarchical world of the 18th century - one that, incidentally, Nicholson is not sure we've escaped. The book's upper-class landowners are never one dimensional, though; they can be as paternalistic and philanthropic as they are blinkered and ridiculously superstitious. They also stand on the cusp of a society beginning to question whether animals are capable of rational thought, language or emotional intelligence.

"The relationship between Tom and these two elephants is echoed by the relationship that exists between servants and their masters in the 18th century," Nicholson says. "There are two things going on here: Tom is the master of the elephants but the servant of Mr Harrington. So it was a way of trying to unlock that society and say something about it. I mean, servants then were treated as essentially lower forms of existence. There's a very famous story of a mistress who would simply undress at night in front of her manservant. She was simply not conscious that he was a rational human being who would notice her being naked."

Nicholson is full of anecdotes such as this, a result of having immersed himself in the world he created. One of the great challenges of writing any kind of historical novel is that the language has to feel right, and in the 18th century language was tight and formal, familiar yet somehow distant. It's testament to his research that in The Elephant Keeper, people can get very angry, but the sentences in which they lose their tempers are somehow restrained. ("I love the writing of that time and I was continually worrying about getting it right," he says.)

Such techniques lend the book a simmering, brooding quality that boils over dramatically in its second half. Tom's bucolic existence in the English countryside is turned upside down when Jenny is sold to another estate. There, he and the elephant witness terrible events, which eventually prompt them to move again, to the terrible confines of a menagerie in London. By this point, Tom appears to be talking to Jenny and receiving advice from her. It becomes a forebodingly dark and unsettling tale - and to be honest, slightly odd. Discussing the possibility of a talking elephant is a rather strange experience, if only because Nicholson and his book are deadly serious about its shift into more metaphorical territory.

"I wanted to write a novel that starts off as a story that could theoretically be true, but changes at the point where Tom is talking to the elephant into something that is clearly not operating in the same area," he says. "It becomes a story about what is just about possible or impossible because the whole point I was trying to get across is that stories that are possible are just as good as stories that are true."

The idea that there is a greater truth in novels than in history books, that even memoir writing is a form of fiction, is hardly new. Famously, James Frey's A Million Little Pieces was supposedly a true account of his addictions until he was forced to go on The Oprah Winfrey Show and admit some had been made up. But does it matter, if the story feels truthful enough to the reader? Probably not. Still, Nicholson takes that further than most, pushing at the edges of relationships between humans and animals and asking what would happen if a human being thought he could not just talk to an animal, but have a conversation with it. In that way it recalls Yann Martel's Booker-winning Life of Pi, with its boy marooned on a ship with a tiger, zebra, hyena and orang-utan. But where that tale has a sweetness to it because the hero is a wide-eyed child, Tom's increasingly strange behaviour is, well, weird. It's such a confrontational idea that it means the rest of the book has to be taken with a pinch of salt. It's worth it, though.

"There is a fine line," Nicholson says. "Tom is apparently going mad, but he has this strange, out-of-body sense that he knows he is. But he never thinks he's going mad in relation to Jenny. He never doubts the fact that he can talk to the elephant and can hear the elephant." There is a pause, almost as if Nicholson realises how earnest he sounds. "Look, I hope people don't decide that he's as mad as a hatter," he laughs. "Because I had to push that relationship just far enough to make people think about the uneasy relationship there still is between humans and animals. That's a better approach, for me, than one where everything ends happily."

The Elephant Keeper is also unsettling because of the stark difference between the green and pleasant land of Somerset and the belching, smog-filled city of London. This, perhaps, is the semi-autobiographical element of the book. Nicholson grew up on the fringes of London, "where you look one way and see this dark city, and turn around and it's all green countryside". He has spent most of his life battling his feelings about both. When he lived in London, the country took on a kind of radiant quality that he takes for granted now that he lives in rural Dorset.

Nicholson was inspired, too, by William Wordsworth's The Prelude, transposing the poet's complete sense of disorientation sparked by the numbers of people walking down London streets to Tom's experience in the London of The Elephant Keeper. "Working out the precise genesis of a book is, in hindsight, very hard," he says. "You can run things right back into your own childhood. I mean, I used to have a little train of wooden elephants that went alongside my bed when I was a boy, so what does that mean?

"But the combination between the countryside and the city in The Elephant Keeper is certainly a part of my experience. When Tom is in London, he's endlessly thinking back to his country life in Somerset, and what he finds is that Somerset, even when he goes back, is a fairy tale existence that is close to being a fiction. He's at the point where truth and fiction are uncertain and even the truth of his childhood, the early days with the elephants, have become a story that he's had to construct in his mind."

The idea of constructing our own life story, of what is true and what is not, gives The Elephant Keeper much of its philosophical and literary heft. Such ideas, allied with Nicholson's interest in the nature of storytelling and the biological ideas of the 18th century, raises the question of whether he was ready for his book to be taken to so many hearts, to appear on awards shortlists and to be, well, popular. As he readies himself for the international paperback release, this is likely to intensify.

"I have written a number of unpublished novels, which are definitely not worse than The Elephant Keeper. In fact, some are better. But they don't contain an elephant. So it may be that the elephant was the key to the success of this book. And that's fine. One could definitely write a more sentimental or populist novel about an elephant, for sure, but there's something indefinable about them that connects with people."

Indefinable for most, but not for Nicholson. He can put his finger on why they've remained an object of fascination for him since that elephant train set by the side of his bed. "I think it's down to how paradoxical they are," he says. "On the one hand they're extremely strong, but they can also be gentle and timid. They're very heavy but they also, somehow, have a lightness about their being. If you've seen them swimming, the weight falls off them and you can almost see their spirit, which is dainty and balletic. They can be intimidating because of their sheer size, but they also know how to have fun."

Was such a fascination difficult to transform into a novel where they have to be more than elephants, where they had to represent something as characters? "They don't signify anything," he says. "I genuinely mean that. More than anything, I wanted to make Jenny a real elephant who wasn't being used as a symbol for something else. To make them concrete, live beings rather than allegories. You see, at the time this book was set, for most people elephants lived in the imagination. So if the elephants were quasi-fictional for them, what I was trying to suggest in the novel is that all storytelling is a matter of exploring levels of possibility."

So if someone tells you a story about a novelist riding through the countryside on an elephant, don't entirely rule it out. The Elephant Keeper (HarperCollins) is out now.