"Give it away. "Go on. I absolutely don't mind if you tell readers that this book is about Patrick Oxtoby, who arrives at a boarding house, kills someone and ends up in prison." Unconventional? The Booker Prize nominee MJ Hyland is certainly that. But it's why she was shortlisted alongside Sarah Waters and Kate Grenville in 2006 for her fiercely uncompromising Carry Me Down.

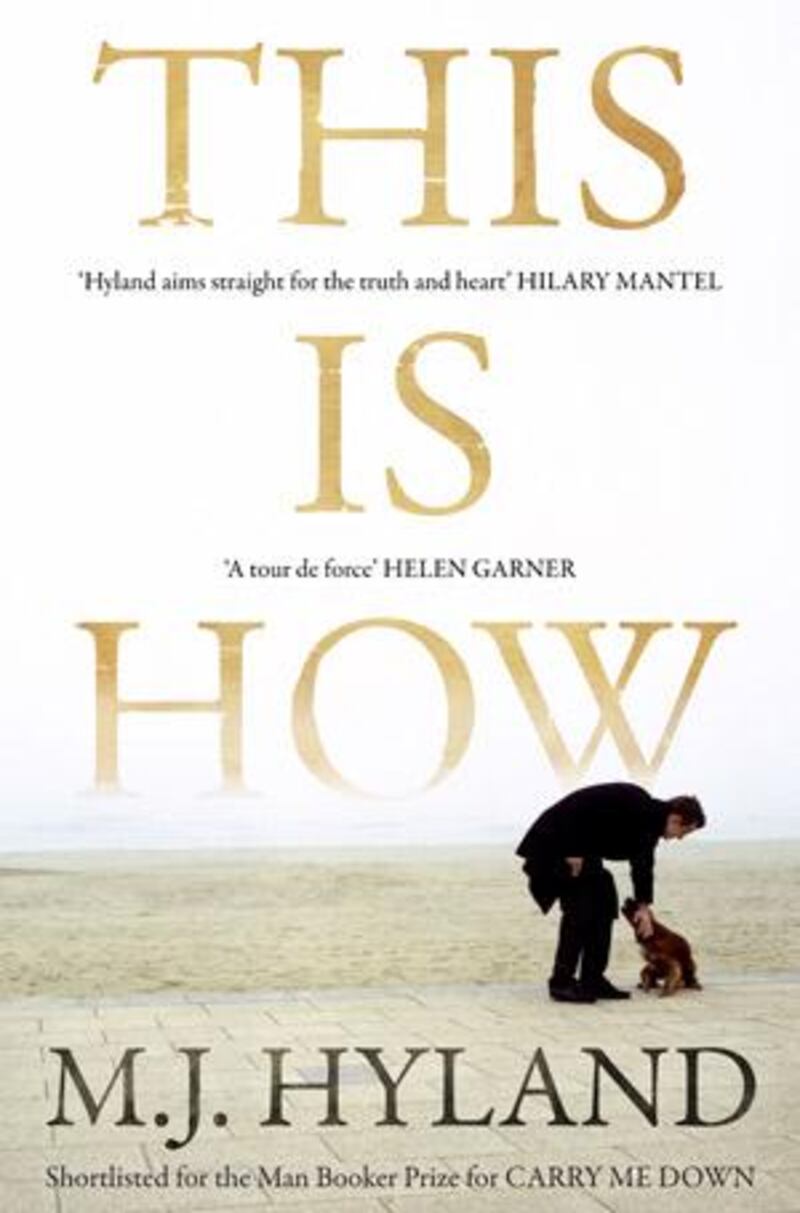

The 41-year old's new book, This Is How, is less a whodunnit as much as a whydidit. It reveals Hyland as a skilful manipulator of the kind of suspenseful feelings you might enjoy in a mainstream crime novel mixed with her background in literary fiction. But surely she is playing with fire if she's so keen to tell us the story. Surely it ruins the suspense that at least half of this book revels in?

"You seriously think that?" Hyland asks from her Manchester home. "If you're telling me that you think it harms the book having that prior knowledge then I think there's something wrong with the book. You just can't tell people who he kills." Hyland, who was born in London and raised in Australia, laughs long and hard. There is a real sense that she had a lot of fun writing This Is How - once she worked out how she was going to tell the story of Oxtoby. It's based on an idea from a book of interviews with killers, Tony Parker's Life After Life. In one of them, all the interview tells the reader is that the murderer was a young man around 20 years old who lived in a lodging house. He was broke, at a loose end, and went into the adjoining room and violently killed his neighbour. It was an unpremeditated, unprovoked murder.

"There was something about the combination of the setting, the idea of an arbitrary murder and a young man without any history of violence committing a crime such as that which really interested me," Hyland says. "When he talks about it he's completely mystified as to why he did it. I love that lack of causation. There's no clear link between anything in his life that had gone before and what he did. I was glued to that idea and wanted to write a book which said this is how that might happen."

So in the book, Oxtoby moves to late 1960s Brighton after his fiancée breaks off their engagement. Instead of enjoying the university life his parents had hoped for him, he works as a mechanic. It's clear from the first page, when he arrives at the boarding house - "I should say something but I can't think what" - that we are dealing with someone with repressed emotions who can't express himself. We learn that those were the reasons his fiancée left him and, fascinatingly, we can understand her as well as empathise with him. But it's also claer that Patrick has a violent streak. Hyland makes sure it's obvious.

"I'm really fascinated in the moments where life goes wrong and, more specifically, the speed at which someone can snap. It's not something unique to people who are in prison - we're all capable of it, definitely. And the trick, the challenge if you like, is to weave that everyday human characteristic into, essentially, a crime-writing style that I genuinely hope unsettles the reader and causes real discomfort."

She laughs again, which only seems to confirm that she must have revelled in shaping that discomfort in the filmic first half of the book. Oxtoby picks up a bread knife after an argument... and cuts some bread. "You have to have that foreshadowing," she says. "And any reader with a nose for this sort of thing should find the first half of the book enjoyable in that sense because you can almost delight in the suspense, the threat, the menace. I know I did."

Hyland is open like this - utterly unlike most guarded authors with books to promote. And although she did, in the end, enjoy the process of writing This Is How, she's just as keen to reveal that it wasn't always such plain sailing. Oddly for someone who can seem so self-assured and relaxed about her work that she doesn't care about giving her story away, she says the Booker nomination three years ago provoked a lack of confidence in her writing.

"I cannot tell you how difficult it was to write This Is How," she says. "I was trying initially to write in a different, perhaps more writerly way, trying to prove my intelligence. Because when it comes down to it, my style is deceptively simple and I wanted someone to say, one day: 'What a beautiful writer' or 'What an extraordinary writer.' I really don't think I'm going to get that writing in this pared back, minimalist way."

And that got in the way of telling the story? "Absolutely. All those feelings were completely interfering with it. It's absolutely key that with a book like this you have an intimacy with Patrick, you feel like you could love him or argue with him like you would with a family member. So that's when I went back to how I know how to write, where it could feel like this story was being told by someone who could really exist, who you could shout at, who you could shake. An intense intimacy with the voice of the narrator was absolutely what I wanted, almost so you get an experience akin to mind reading. I knew I had it when I disappeared, if that makes sense."

She got there in the end; and it's crucial that she did. Because for this book to work, you have to believe in Patrick, feel his tragedy even though he does something so appalling that he's locked up for life for it. The second part of the story is set in prison and echoes the first; in the boarding house he shares with two male strangers, and in prison he bonds with two men. What's so sad is that, finally, Oxtoby finds a kind of peace and a better understanding of who he is in prison.

"There are very deliberate parallels between the two halves," Hyland says. "The relationships in the boarding house he completely messes up and yet paradoxically, ironically and tragically, he does better with people in prison whom he would never have dreamed of having anything in common with." What a strange place to find your way in making relationships. "Totally. But he realises he's probably happier inside. My favourite line in the whole book is: 'Life seems to be shrinking to a size that suits me better.' I love that line. It's so awful how somebody might feel more comfortable in a place that most of us would regard as some kind of hell."

It's some kind of late 1960s hell, too. There is an odd mix of boarding houses and cafes; it's the kind of place some readers may feel familiar with and simultaneously are thrown off kilter by. But it wouldn't be the same if Oxtoby had decided on his next course of action over a Starbucks latte. "It was supposed to have this dreamlike, amorphous feeling to it. I could never write a novel that has props such as mobile phones, computers, Ikea furniture. Awful. But for the purposes of the drama, it did have to be set then so Patrick couldn't be rescued by technology. Some of the things that befall him definitely would not have occurred if he'd had a mobile phone - it's as banal as that in a way. Does that say something about the differences between then and now? Maybe it does."

Oxtoby is that mass of contradictions and you find yourself conflicted between expecting he'll get the punishment he deserves and desperately hoping life will turn out all right for him. I wonder if she was ever tempted to give him a Shawshank Redemption-style ending. "It couldn't have a happy ending," she says, this time not proposing to give away exactly what that ending is. "That's not the kind of book I wanted to write. It needed to be sad. There is some light there of course, which makes the darkness all the stronger. I don't think it's an oppressive book at all. But then, my favourite form is tragedy."

Her voice crackles with a directness and purposefulness that is reflected in her writing. It makes you fear for the students she teaches at the University of Manchester's Centre For New Writing alongside Professor Martin Amis. "I often have to explain to students why something they've written really stinks. And it's really good for my brain to be forced to articulate that. It also gives me an added fear about writing badly. What it's confirmed to me, though, is that if it's not intense, perhaps violent, offering menace or threat, then it's a bad drama."

In that sentence, Hyland sums up the book - it's a great drama, but it's also about a damaged soul, a flawed human being who, in one regretful but possibly inevitable moment, changes the course of his life forever. "I've had some beautiful early reviews, some dream ones," Hyland says. "But I've also had some rotten ones and, you know, I kind of saw them coming. It's the voice of Patrick: if you don't believe in him, if you don't bind with him - which I concede is possible - then This Is How is not just bad for you, it's diabolical."

It's not what you expect to hear from an award-winning author. "But then, you don't expect to turn up to a book event and hear me say: 'Right, this is about Patrick Oxtoby, who kills someone and he's just arrived at a boarding house' and start reading, do you? That's what I did. And when it comes down to it, I had an hour-long queue of people I'd given the plot away to. They still wanted to read the book, still wanted to know, essentially, This Is How."

This Is How (Canongate) is out now.