A recent editorial chiding the South Korean president Park Geun-hye in Rodong Sinmun, North Korea's newspaper of record, started as it meant to go on. Under the heading Political Whore, the editorialist accused president Park of "oiling her tongue on Obama". This at least has the virtue of being a striking image. Other North Korean outlets have described her as a "despicable prostitute" "dirty comfort woman" and "capricious whore". Her predecessor as South Korean president, meanwhile, was always characterised as "the rat-like Lee Myung-bak".

So it goes: another day, another example of rhetorical aggression from Pyongyang. The obvious method in this public relations madness is to give onlookers the impression that North Korea is a dangerously unpredictable place, best left alone or treated very carefully.

Before defecting in 2004, Jang Jin-sung, the author of this much-anticipated “memoir”, was one of the Admitted – those privileged enough to have met in person the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il. Jang served him as court poet and a counter-intelligence officer in the Pyongyang regime’s United Front Department (UFD).

One of the lessons of Dear Leader is that North Korea is often at its most calculating when it appears to be at its most unhinged. Keeping onlookers uncertain is a distancing strategy that allows it maximum policy leeway; if your words cause alarm at what you might do next, especially with your small but functioning nuclear arsenal, whatever you eventually decide to do will usually come as a relief. Nor are deranged insults the only weapon in Pyongyang's rhetorical arsenal. They alternate with pathetic wheedling, deluded self-praise, pompous sentimentality and the occasional sickly trickle of idealism, according to the needs of the moment.

All of this white noise allows Pyongyang to occupy itself with its main task: the erection and maintenance of the Kim dynasty, now in its third incarnation, as the supreme deity and godhead of the North. Backstopped by a physical surveillance network of unparalleled intrusiveness, this job occupies the majority of the time and effort of what North Korea has for a cultural industry. The Kims are praised in song and story; in the daily papers and the nightly newscasts; in the history books and in the curriculum. Deaf children are taught to portray the late Kim Il-sung in sign language with a thumbs-up left hand, signifying “number one” while the right hand makes a fist, signifying the total support of the people.

Jang slotted into this scenario as a court poet. Poetry was important to Kim Jong-il, then the Dear Leader (North Koreans, according to Jang, simply knew him as The General), who sought to “rule through music and literature”. His father, Kim Il-sung, liked big, meaty novelisations of history with himself as the hero. The younger Kim preferred to be idolised in a more succinct format (the current incarnation of the deity, Kim Jong-un, doesn’t appear to read much of anything). And besides, the country was in the midst of the Arduous March, which is what the regime chose to call the period of economic collapse and endemic famine it plunged the North Korean people into after the dissolution of the Communist bloc. So paper was short and poetry therefore convenient.

At this time, Jang was a rising star in the UFD, the part of the regime that specialises in propagandising to and among foreigners. This involved literary and cultural work, and so when the job of writing a poem in praise of Kim Jong-il was put out to tender, the UFD was one of several government departments that competed for the job. As an employee of Division 19, an office created specifically to fabricate poetry in praise of Kim Jong-il by imaginary South Koreans, Jang was given the job.

Jang had to come up with a way of glorifying North Korea’s Songun policy – military first – as a force for both Korean unification and world peace, and from there commend the wisdom, farsightedness and personal glory of Kim Jong-il, the policy’s author. Since the real aim of Songun was to establish North Korea as a nuclear-armed state, this was a tricky assignment.

He finessed the job by positioning Kim Jong-il as the protector of all Koreans, North and South, whose Songun policy would guarantee peace and independence across the peninsula: “the general alone/is Lord of the Gun/Lord of Justice/Lord of Peace …”

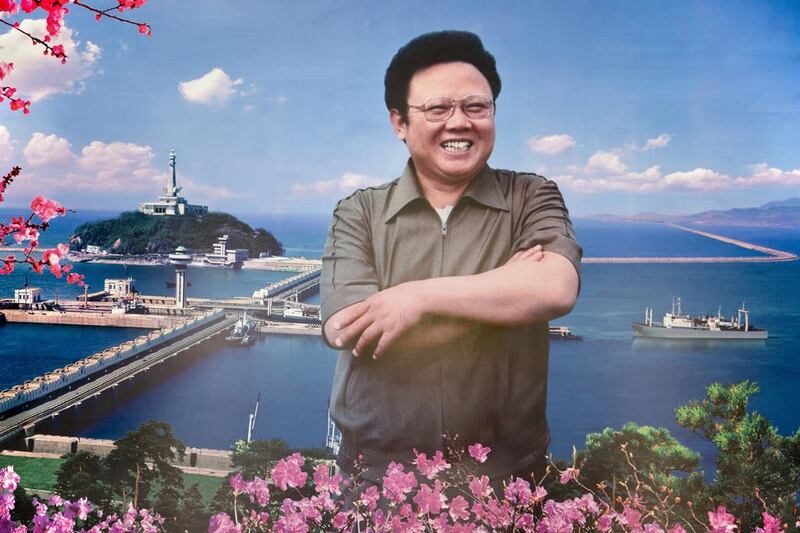

Spring Rests on the Gun Barrel of the Lord, as the poem was called, was published in Rodong Sinmun and won its author a personal interview with Kim Jong-il himself. This was the point where disillusion began to kick in. The General turned out to be a flabby, pallid man, teetering about on shoe lifts. His first words to Jang consisted of a threat to have him shot unless he named the real author of his poem. "It's a compliment, you silly bugger," Kim added, as Jang swooned in terror.

If Kim’s appearance and behaviour were a let-down, the steady attrition of Jang’s loyalties came about as a consequence of his day job, in which he was required to immerse himself in South Korean books, music, newspapers and literature. It wasn’t just that this gave the lie to propaganda about the South, but that local writers were discussing political and social problems with a frankness that would have got them and their families shot in the North.

Naturally, taking any of this material outside the office was also a matter of treason, which Jang inadvertently committed when he lent a South Korean book to a friend, who lost it on the Pyongyang subway. Both Jang and his friend decided to leave before the inevitable happened.

From this point on, Dear Leader changes from the story of a regime insider to that of a typical fugitive from tyranny: constantly on the run from both the North Korean and Chinese security forces and dependent on the kindness of strangers from China's ethnic Korean community. After many vicissitudes, Jang's friend is cornered by the security forces and kills himself. Jang finally makes it to the South Korean embassy in Beijing and from there flies to a new life in Seoul.

Jang’s attitude towards China reveals the pervasive interpenetration of Pyongyang’s ideology with the lives of the North Korean people. Where westerners tend to wonder if or when the Chinese people will rebel against their dictatorship, Jang is amazed at the way people simply go about their daily business without any regimentation at all, never once praising their leadership. They had what was to him the almost inconceivable liberty of indifference to whomever happens to be in charge. Interestingly, according to Jang, the government in Beijing has little but contempt for the Kims, structuring the occasional visit by the God-Kings of Pyongyang as elaborate exercises in humiliation.

After leaving the North, Jang worked for a time with South Korean Intelligence. He now operates New Focus International, a group of former regime insiders who offer reporting and analysis about North Korea drawing directly, they claim, on news clandestinely gathered from highly placed sources within the North Korean government.

Most NK watchers see the Kim regime as a simple matter of dynastic progression, enlivened by harem intrigues: Il-sung begat Jong-il who begat Jong-un. For Jang, Kim Jong-il is the pivotal figure. Through his control of the Organisation and Guidance Department (OGD), basically the regime’s human resources arm, Kim the second reduced his father to a figurehead in the last years of his rule. Kim Jong-il’s own sudden death left the OGD as the organisation in charge, which uses the Kim cult as a means of ongoing regime control and Kim Jong-un as a puppet deity. So while the execution of Kim’s uncle Jang Song-thaek at the turn of the year was commonly viewed as the younger Kim discarding his regent to assume full control, Jang sees it as a successful coup by the OGD to purge a threat to their control of Kim.

We're never going to know exactly what's going on under the regime until it finally ends. Indeed, the bizarre obfuscation of the Kim dynasty contributes to its longevity, as does the way we often tend to respond to it. It's hard not to laugh at Kim Jong-un, the bouncing baby tyrant, as he gestures excitedly at a shooting range or ski jump, while men 50 years older than him wearing improbable hats scribble in notebooks. It's outrageous in the sense of being ridiculous. What Dear Leader reminds us of is the fact that the existence of the Kim dynasty is also simply an outrage.

Jamie Kenny is a UK-based journalist and writer specialising in China and its growing interaction with the rest of the world.

[ thereview@thenational.ae ]