It was a grim twist in a sinister chain of events that began more than 18 months ago. Novelist and former newspaper editor Ahmet Altan was on Tuesday rearrested by Turkish police just a week after his release from prison. Altan had received a life sentence in February 2018 for his alleged involvement in the failed 2016 coup in Turkey. The Supreme Court overturned those convictions in July but this month he was convicted of aiding the network of US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, whom Turkish officials identified as the mastermind of the attempt to overthrow President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's government.

Altan, 68, was released on time served, but he is among hundreds of thousands investigated and tens of thousands arrested and charged for being allied with Mr Gulen and the deadly attempted coup during a widespread crackdown that drew international criticism and charges that officials were attacking press freedom. About 30,000 remain jailed.

As a critic of the regime, the writer always knew the powers that be would come for him one day.

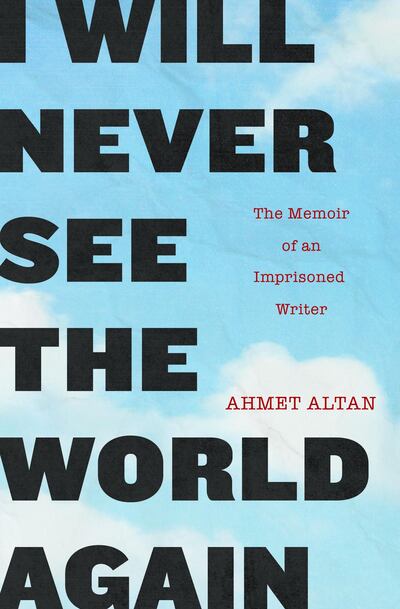

Rather than suffer in silence, Altan has opted to speak out, albeit by way of his pen. His memoir I Will Never See the World Again is an eloquent response to his sealed fate. It comprises 19 short yet substantial chapters which Altan gave to his lawyers at Silivri Prison, Istanbul.

They were then sent, one by one over seven months, to Altan's friend Yasemin Congar, who has translated them beautifully. Each chapter coheres into an impressive whole which magnifies the power of the written word and the resilience of the human spirit.

Altan begins with the day he lost his liberty. Early one morning in September 2016, he is woken by six police officers with a warrant to search and arrest.

As they comb his flat he reflects on how history is repeating itself, for on a similar morning exactly 45 years ago, police raided his childhood home and arrested his father. Now it is the turn of Altan and his brother Mehmet. The pair are taken to the Security Department and placed in separate cells. "In a matter of hours," Altan writes, "I had travelled across five centuries to arrive at the dungeons of the Inquisition."

So commences his ordeal. Altan shares a dark, airless cell with various "cagemates": a young teacher who was forced to sell out his friends, a fretful colonel whose daughter, 3, is in hospital "grappling with death", plus police officers who protest their innocence (one was on holiday with his family on the night of the coup). Meals consist of frozen sandwiches. The bathroom is so filthy that Altan showers in his socks. The absence of mirrors exacerbates his disorientation: "I wasn't there," Altan notes. "It was as if I had been erased from my life."

Twelve days later, he and Mehmet are brought to a courthouse where they learn they have been detained on charges of “putschism”. “If only you had stuck to writing novels and kept your nose out of political affairs,” the judge tells Altan. Mehmet is sent to prison but Altan is released. However, this reprieve is quickly overturned. That same evening, he is arrested and incarcerated in the same high-security prison as his brother.

There is much to get used to. His new home measures six steps by four. His new cellmates come from completely different cultures:

“It is as though we had been brought together by a playwright and not by the prison administration, since our identities embody enough conflict and tension to see an entire play through to its climactic end.” And his new plight comes with no prospect of pardon or parole.

Many writers have given accounts of their time in prison after the event. Altan, like Oscar Wilde and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn before him, belongs to that more select group whose members have documented their detention while behind bars. As such, his impressions feel urgent and immediate, sharply focused and strikingly real.

In places, his prose is death-tinged. Mehmet relates how in mythology the corpse only discovers it is dead when the funeral crowd disperses and it tries to sit up but bangs its head on the lid of its coffin.

Altan makes the same discovery but in the back of a police car: “When the door closed, my head hit the coffin lid.” During a rare low ebb in his cell he takes stock of both the finality and futility of his predicament: “I was alive,” he declares, “but life was dead.”

And yet his book is no tale of woe. Not once do we hear a howl of rage or cry for help. Altan takes pleasure in flagging up absurdities (in prison, his doctor is a gynaecologist and his barber is a tailor). He regularly allows his imagination to run riot, provides searching meditations on literature, history and humanity, and spares emotional thoughts for the loved ones he left behind.

At one point Altan sees himself hanging from a branch over an abyss. Despite the odds, he vows to stay strong and hang on in there. We should salute his courage and endurance, and we should read his remarkable memoir.