The arrival of Spielberg's 3D The Adventures of Tintin on the big screens is likely to see bookshops quickly stock up on the various adventures of the iconically quaffed Belgian boy reporter - 24 books in total. Sales of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, The Crab with the Golden Claws and Red Rackham's Treasure (the three books that make up the film currently showing on UAE screens) will no doubt skyrocket, but should anyone pick up a copy of Hergé's second Tintin outing, Tintin in the Congo, they'll notice something rather unusual for a children's cartoon book: a disclaimer. "In his portrayal of the Belgian Congo, the young Hergé reflects the colonial attitudes of the time. He depicted the African people according to the bourgeois, paternalistic stereotypes of the period - an interpretation that some of today's readers may find offensive."

Books: The National Reads

Book reviews, festivals and all things literary

[ Books ]

And what offence has been found to have been caused since this book was first published in 1931. Following on from the success of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, it was Hergé's editor Norbert Wallez who wanted the cartoonist to take his character to the Congo, then controlled by the Belgian imperialist government, believing the colonial regime needed to be promoted. Hergé himself had never visited and drew his knowledge of the country almost solely from the writings of missionaries. The result is shocking, with the Congolese shown as semi-naked imbeciles, lazy, and almost unable to think for themselves, patronised by their pith helmet and safari suit-clad Belgian rulers who help introduce them to "civilisation". In reality, the Belgian Congo was one of the most brutally oppressive systems in Africa's history, the personal possession of King Leopold and the original inspiration behind Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

Interestingly, it wasn't the racism that was the first cause for complaint, but Tintin's utter contempt for Congolese wildlife. By the time he leaves Africa, the plucky reporter has shot 13 antelopes, killed an ape to wear its skin, injured an elephant and stoned a buffalo. In one of the most gruesome scenes, he blows a rhinoceros up with dynamite, having drilled a hole in the animal's back in which to place the explosives first. When the book was first published across Scandinavia in 1975, Hergé was asked to replace this page with a less violent scene. The cartoonist, who had come to regret the animal abuse and big-game hunting he had drawn, quickly agreed.

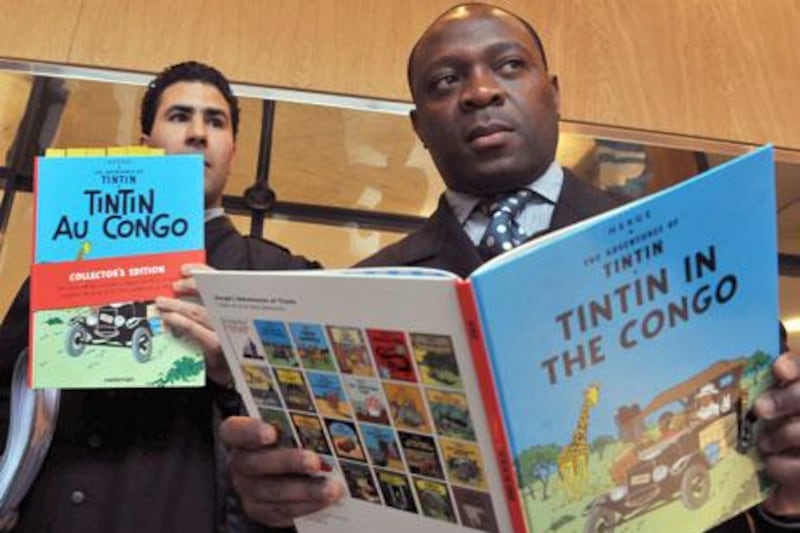

Due to its controversial nature, Tintin in the Congo was the last book to be published in English, coming out in 1991, 60 years after its original release. But although colonial attitudes had long since changed and the stereotypical references in the story could be viewed as a certain historic reflection of the time, the book still drew opposition.

When the Congolese information minister Henri Moya Sakanyi accused the Belgian government of nostalgia for colonialism in 2004, he claimed that it was like "Tintin in the Congo all over again". In 2007, following a complaint from the Commission for Racial Equality, Borders bookshops moved the book from the children's section to the area for adult graphic novels. The same year, a Congolese man living in Belgium attempted to get the book taken off shelves in Tintin's home country. "It makes people think that blacks have not evolved," he said.

Just as he did with his disregard for the animal kingdom, Hergé soon became embarrassed by his portrayals in Tintin in the Congo. In the 1946 edition of the book, he cut many of the references to Belgium and colonial rule. One scene saw Tintin teaching Congolese children about geography. "My dear friends, today I'm going to talk to you about your country: Belgium!" This was altered to a maths lesson, but still didn't manage to avoid causing offence. "Now who can tell me what two plus two make?.. Nobody." Later, in the 1970s, Hergé expressed further remorse over the book. "I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved," he said.

But although Tintin's adventure in central Africa was perhaps his most notorious, it wasn't the only time Hergé came under scrutiny. In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the Bolsheviks were depicted throughout as villains. Hergé later blamed this as "a transgression of my youth". In The Shooting Star, the American villain had the Jewish surname of Blumenstein and displayed some stereotypical Jewish characteristics. In subsequent editions, this character became Mr Bohlwinkel and later - after he discovered that Bohlwinkel was also a Jewish name - a South American from the fictitious country of São Rico. Perhaps worst of all, Hergé was accused of having Nazi sympathies, having continued working at his paper when it was taken over during the Second World War.

Whether Hergé himself was a racist, or simply reflected the average attitude of Belgians in the 1930s, is unknown. What can be assured is that the film adaptations - which look set to continue, given the box-office success of the current 3D blockbuster - are unlikely to feature any hint of the stereotypes in the books. In fact, given that Spielberg is at the helm, don't be surprised if Tintin in the Congo is the one book that never makes it to the big screen.

Follow us on Twitter and keep up to date with the latest in arts and lifestyle news at twitter.com/LifeNationalUAE