Craig Thompson's Habibi is a wonder: a rich, gorgeous and boldly ambitious fairy tale about love and spirituality, the ancient and the modern, East and West and the decline of the natural world. It's also something of a disappointment.

Thompson first gained renown in 2003, with his semi-autobiographical debut, Blankets. That book recounted his blush of first love in rural Wisconsin and his decision to leave the evangelical Christian faith of his parents. It earned great acclaim and half a dozen awards. With his new work he has set his sights still higher.

The story opens in an Arabia-like desert facing severe drought. Desperate to survive, a father marries off his daughter, Dodola, inexplicably named after a Slavic rain goddess, to a gruff, older scribe. He whisks her away and takes her virginity, then teaches her to read and write. One night, thieves ransack their house, slash the scribe’s throat, kidnap Dodola and sell her into slavery.

At the slave market she comes across an abandoned, dark-skinned, three-year-old boy, Zam. When Dodola escapes into the desert she snatches the boy and takes him with her, to raise as her “Habibi”, or darling. For nine years, they live in an abandoned boat beached on the dunes as Dodola sells herself to men in passing caravans in return for provisions.

The adolescent Zam follows her out one day and watches as she is raped, crouching in angry fear behind a camel. He curses himself, then goes out searching for food. “We could be reclaimed as slaves at any time,” she says when he finally returns. “[Zam] didn’t understand that our world was dying. People were crying out for water, but the sources had dried up,” Dodola thinks to herself. “However, the masses will need something to distract them from destruction ... and my body will still be a commodity.”

As the last in a series of images, we see Zam beneath Dodola’s closing thought: “This is the world of men.” When Zam goes out foraging a second time, Dodola is snatched up by bounty hunters who hand her over to a drooling, pot-bellied caricature of a sultan. She becomes his aphrodite, the favourite among his well-stocked harem.

That common Arab cliché is just one among a handful of Orientalist stereotypes in the book: desert caravans filled with rough merchants, dirty souqs, frolicking harem girls, despotic, turbaned leaders, subservient eunuchs. It’s often hard to tell whether Thompson is using them to titillate and entertain or to comment on their questionable use in ages past.

If Dodola is not being ravished by one man or another, she is being fantasised about. And unlike R Crumb and a handful of other popular graphic artists, Thompson clearly relishes form, shape and movement.

Dodola is a raven-haired beauty, with saucer eyes, broad lips and a petite, hourglass figure. As a youth, Zam is slim and dark, catlike. Fully grown he is massive, imposing, filling the scenes with his bulk. His size and blooming desire compound his fear of further hurting Dodola, making him uncomfortable around her after he witnesses her violation.

After her disappearance he goes out searching for her and falls in with a group of hijras. During the scene of their reuniting, years later, Zam flashes back to Dodola telling him the story of Noah and the flood.

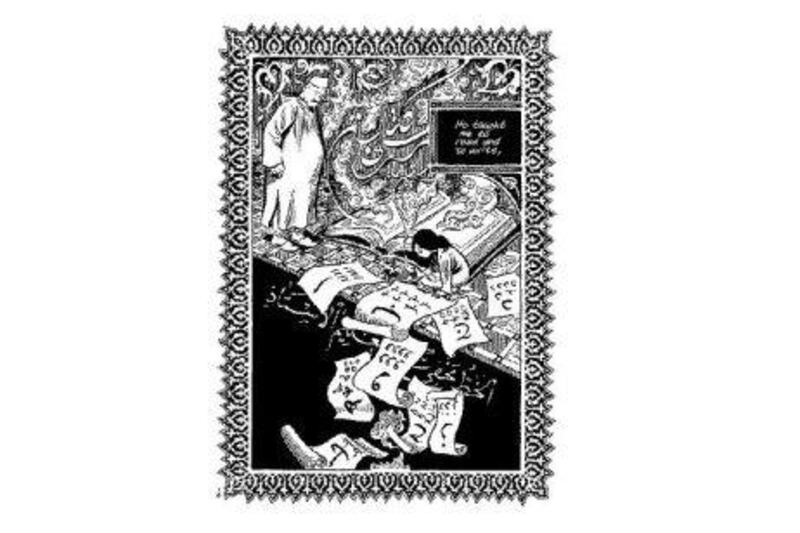

Throughout the book, well-known religious tales unspool with regularity, often before a backdrop of phantasmagorical images or flowing Arabic calligraphy. In an apparent attempt to bridge the divide between Islam and Christianity, Thompson includes several stories shared by the world’s two most popular monotheisms: Adam, Abraham, Noah and others are mixed in with quotes from the Quran and bits from the Bible.

But as one who has lived and worked in the Arab world, I was left wondering: where are the Muslims? What’s missing from the religion in Habibi are the religious. To Thompson, the Arabic alphabet is protean and pliant: a shifting tapestry of symbol and anecdote that he wields to often glorious effect, highlighting the links between Arabic script and Islamic geometry and endeavouring to make Islam less foreign to his mostly Western audience. But he approaches religion with a certain detachment – perhaps a hangover from his distasteful experience with evangelical Christianity.

None of the characters is shown in prayer. None embraces Islam as a guide to living, a moral compass, or anything other than a well of stories to be dipped into as needed. For a book so laden with religion and spirituality, it's all a bit soulless, as if the narrative takes place in the unruly idol-worshipping era of jahaliyyah, before the revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Mohammed.

The actual when and where of the story seems fluid, shifting from medieval Arabia to something resembling 21st century Dubai in the space of a few pages: a lavish apartment in an under-construction skyscraper abuts a medieval souq where slaves are sold to the highest bidder. Beyond the Bible and Quran, Habibi incorporates references to the Arabian Nights and Scheherazade, poems from Rumi and bits of alchemy and astronomy.

As in Blankets, Thompson employs flashbacks and more than 600 pages of lush, graceful drawings in the service of a long, winding tale. But Habibi is far more sweeping, covering the bonds of servitude, the shame of fantasy, the complexities of love, the fragility of the environment, the ignorant greed of humanity, as well as Allah, the Prophet Mohammed

and the possibilities of Arabic script.

Thompson is a dazzling artist and a fine storyteller, ranking among the finest graphic novelists today. But Habibi sets a nearly impossible target. Too much sensationalism, too much religious mumbo-jumbo and too little of the human spirit undermines the work. And in the end, the lessons of the narrative are ambiguous and possibly contradictory.

Still, being brought low by ambition is the least damning of literary failures. Habibi is a ripping yarn, often beautifully told. If Thompson tries too hard to pass it off as a moving and important work of art, it’s a credit to his skill that he nearly succeeds. Call it a marvellous failure.

David Lepeska is a freelance writer who contributes to The New York Times, Financial Times and Monocle, and previously served as The National’s Qatar correspondent. He lives in Chicago.