There are few grander – or more gruelling – spectacles on the sporting calendar than the Tour de France. The sight of the yellow jersey in the thick of the peloton thrills spectators as the pack winds its way through picturesque French villages and up steep Alpine climbs.

The Tour has seen its share of incredible feats of endurance – this year, for the first time ever, a Brit may ride off as the overall champion when the riders zoom down the Champs-Elysees tomorrow – and awe-inspiring legacies like those of Merckx or Hinault (also scandal, sabotage and allegations of doping galore). But few riders’ stories are as gripping as that of the Italian Gino Bartali, who won the Tour in 1938 and 1948. For any rider, repeating a Tour victory is a supreme challenge but to do it a decade after the first win – a lifetime in cycling years – is no less than miraculous.

Bartali’s achievements as a rider are notable, yet the cyclist also has a place in history for his bravery during the Second World War. Using his celebrity as cover, Bartali sheltered a Jewish family and helped many others by working with the underground during the Nazi occupation of Italy. He distinguished himself in dangerous times, then made an incredible comeback as Europe rose from the rubble of war.

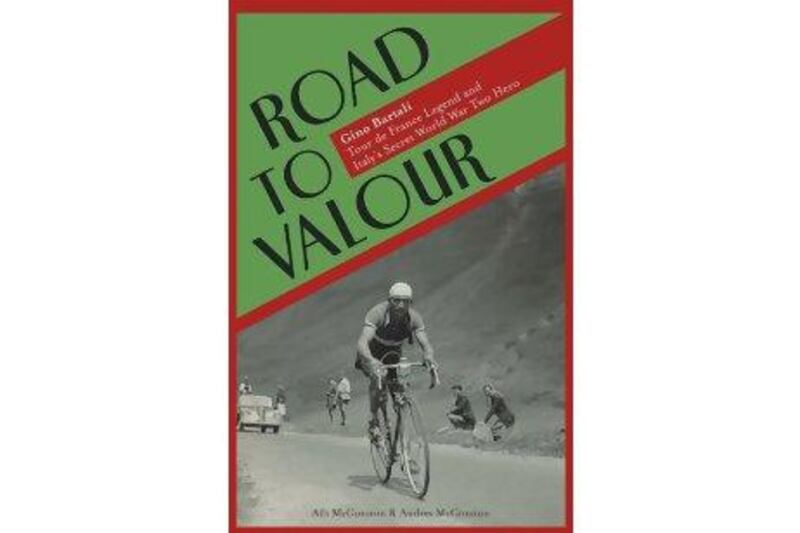

In Road to Valour, the brother and sister writing team Aili and Andres McConnon tell Bartali’s story with workmanlike efficiency. For all the colour of his life – were it fiction, we’d think it an outlandish story – the McConnons play up the maudlin theatrics and inspirational lessons. Still, Bartali is such a fascinating character it would be hard to write a bad book about him, and the authors provide a solidly researched context that takes in the history of the Tour, the rise of fascism in Italy, the horrors of war and the rigours of cycling in the pre-doping era.

Bartali, who was born in 1914, rose from unpromising surroundings in the village of Pont a Ema, near Florence. His father worked as a labourer and part-time bricklayer. The family lived in a tenement building with no running water. “As children we had fun with little, in fact nothing,” Bartali recalled. Bad grades led the young Gino to cycling: a chronic underachiever, his father ordered him to complete sixth grade but, to do that, he had to go to Florence by bike. He soon became obsessed, getting work in a bicycle shop and whizzing through the streets. The elder Bartali did not approve of racing, but relented when his son’s talent became obvious.

The McConnons weave politics into the story of Bartali’s rise through the cycling ranks. His father was a socialist, a dangerous vocation in Mussolini’s Italy. Gino, the authors write, “would come to understand politics as the elemental force that it is – singular in its ability to build up a man or tear him down, unify a country’s citizens around a common goal or turn them against one another in bloody persecution”. Bartali tried to keep his distance from politics – he moved closer to the church, looking for a spiritual refuge from temporal burdens – but Italy’s fascists, looking for virile exponents of their creed, found the perfect symbol in Bartali. With back-to-back wins in the Giro d’Italia in 1936 and 1937, Bartali found fame and fortune. The Tour beckoned. A crash ruined his first try in the 1937 Tour and he was forced to withdraw. He maintained that the fascists were behind this turn of events, though the authors adduce no proof of the charge. All his efforts would now be directed towards the 1938 Tour de France.

Bartali was a master of the mountains; he would bounce up and down in his saddle, now standing, now sitting, an unorthodox technique that puzzled other riders (“He looked like he was being electrocuted,” said one rival). He specialised in “risky, all-or-nothing offensives”, the McConnons write. He crashed; but he also burnt brightly. Such techniques led him to victory in the 1938 Tour. Not surprisingly, he dominated the mountain stages. When the war came, Bartali took up a far more dangerous mission.

Drafted into military service, he avoided combat due to an irregular heartbeat, a condition that did not impede his athleticism. He became an army messenger and was allowed to keep a bike. He had the perfect cover for his next assignment. In 1943, a call from the archbishop of Florence persuaded him to ferry forged identity documents for Jews who were being deported to death camps as the Nazis cracked down. Of his decision, the McConnons write, a touch melodramatically, that “the siren call of self-preservation was deafening, but a nobler impulse beckoned”. Bartali, seemingly a racer in training, did his job well and he was often asked for his autograph as he wheeled his precious cargo, stowed in his cycle’s frame, from safe house to safe house.

He gamely indulged the comments from amateur cyclists in the soldiers’ ranks, even as he feared he might be found out. He even survived a brutal interrogation from a sadistic army officer. Bartali’s strong legs and cunning saved many lives, but he also put up an apartment to shelter the family of a Jewish friend he had known since childhood.

The war took its toll physically and emotionally. His wife gave birth to a stillborn child. His work for the underground saved many families, but Bartali was reluctant to play up his heroism. He looked to cycling again. Yet, in a country reduced to ruins, the sport became an afterthought for Italy’s once-ardent fans. Bartali recalled mournfully of this time, “the triumphant years of the pre-war period – the championships, the Giro d’Italias, the hard-earned wins – were far away. It seemed like they had been lost in that deafening uproar that had shattered nature and souls”.

When racing resumed, he was in danger of becoming forgotten. A rival Italian, Fausto Coppi, had risen to prominence and threatened to supplant Bartali. The 1948 Tour would settle the matter but Coppi declined to ride in a subordinate role and sat out the race (he would win in 1949 and 1952). Bartali’s sheen had dimmed; one Belgian rider called him a “very normal, second-class rider”. The press dubbed him Il Vecchio, “the old man”, even though he was only 33. He shot back with bursts of temper, which only earned him another sobriquet, Ginettacio, or Gino the Terrible.

It was a fraught race from start to finish, not least because of the intrusion, again, of Italian politics. The fascists had been swept aside, only to be replaced by an unstable democracy. When a leading politician was shot and gravely wounded, Bartali was called on to win and unite his country with a victory.

The McConnons's section on Bartali's final Tour win is the Road to Valour's most gripping. Against the pressures of the home front and the depredations of an ageing body, Bartali made up an incredible 21-minute deficit in the mountains. Freak cold weather in July swept through the Cannes-Briancon stage, which took riders deep into the Alps. Against sleet and snow, Bartali hurtled ahead and won the stage and then the race. Maurice Chevalier, the French actor, yelled "Bartali – you're immortal!"

Cycling again won Bartali celebrity and gave Italy a measure of joy during a political crisis. Many say tensions were eased after his win. For his part, Bartali could only offer modesty: “I don’t know if I saved the country, but I gave it back its smile.”

Matthew Price’s writing has been published in Bookforum, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe and the Financial Times.