"Nearly 30 years ago, just after I wrote my book about Delhi, City of Djinns, I won a prize for it," says writer and historian William Dalrymple. "I had always loved pictures, so I decided to invest the money in a painting. I bought what was then called a 'Company School' picture."

Thousands of this type of painting were made by Indian artists in the second half of the 18th century to reflect the taste and specifications of a new class of patron in India: the officials of the East India Company. "Thirty years ago there was not a huge amount of prestige around the genre," says Dalrymple. "You could buy a museum-quality Company School picture for £1,000 [Dh4,586]."

That is no longer the case. Company paintings are suddenly very much in the news, as a result of an exhibition at the Wallace Collection in London, curated by Dalrymple, of some of the greatest examples of the genre.

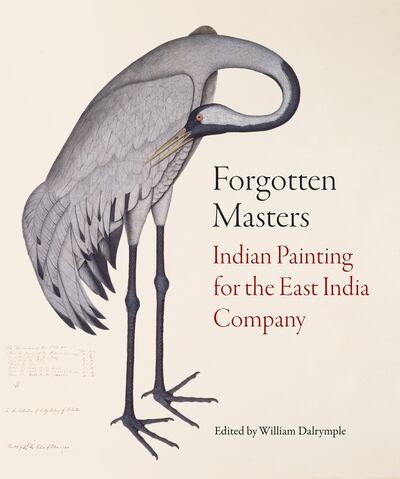

Titled Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, the show caused a huge stir in England, bringing art critics to a belated appreciation of the genius of obscure artists such as Shaikh Zainuddin, Bhawani Das and Haludar. The exhibition, which has now closed amid the coronavirus pandemic, was accompanied by a detailed catalogue published by Bloomsbury under the same name (and designed by Dalrymple's brother Robert). The book is now available on Amazon. With scores of beautiful colour palettes and a set of contextual essays by scholars, it is the ideal companion for this time of quarantine.

For Dalrymple, the show – which is likely to be extended to September once the pandemic subsides – was an exercise in restoring to the mainstream works from an understudied period of Indian art history, as well as an act of revision – of reperception. “It’s time to say goodbye to the distorting phrase ‘Company School’ and shift the focus from the British patrons to the actual Indian painters,” he says. “You don’t look at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and say the credit for it goes to Pope Julius II. You honour it as the work of Michelangelo.”

Many of the paintings in the book are strikingly intimate, detailed, realistic pictures of birds and animals, plants and flowers – a far cry from the ornate and teeming figurework usually associated with Indian painting. So why is this?

In the second half of the 18th century, Dalrymple says, the East India Company, while expanding its footprint as a political power in the Indian subcontinent, became the link between the art of the land and certain newly emerging trends in Europe.

“This was the time that explorers from the great new age of maritime travel were bringing back amazing natural history specimens from other continents. The Kew botanical gardens had just opened in England. All around Europe it had become the vogue to paint, classify and define the natural world, and to publish these in catalogue form. Such books reached the hands of those East India Company officials who had a taste for art; people like the army general Claude Martin in Lucknow, or the judge Elijah Impey in Calcutta.

“Such patrons also found artists who had been put out of work because of the fall of various royal courts at the hands of the Company. So they put these artists to work on the depiction of things that struck their own eye as picturesque in the Indian landscape. Sending such pictures home for them, at the time, it was the equivalent of picture postcards or Instagram posts today,” says Dalrymple.

Naturally, the asymmetry of this intercultural encounter means that the historical record greatly talks mainly of the wealthy, literate, articulate Company patron (who usually also left a trail of documentary records on his life) while excluding the contribution of the unlettered artist, of whose life few details have survived and whose brushstrokes are his only biography. But it is time for that to change, for as the exhibition suggests, these brushstrokes often have a remarkable character.

Consider what was being asked of the artists. Many of the painters featured in the book were trained in the highly ornate and picturesque style preferred by the Mughal Empire, at the time still ruling India. But the European still-life botanical and natural history drawings to which they were now exposed, and asked to replicate, was “raw and confrontational”, Dalrymple says.

Consider the visual pleasure produced by the panache of Zainuddin, a painter employed by judge Impey, in his depiction of a black-hooded oriole. The bird's profile shows off its beautiful two-tone plumage. The viewer can almost feel each brushstroke that creates a yellow feather upon the black wing, and note the arch of the bird's back.

The oriole’s pose and gaze are jaunty, it stares at something outside the visual field with a beady red eye. The painting is actually a double study: the oriole perches on a branch extending from the stump of a jackfruit tree, commonly used to make furniture in India. Little blue tints lend a touch of mystique to the tree, and on examining closely, you'll see a large camouflaged insect crawling up the stump. The effect is one of pleasure in the natural world, with notes of mischief and whimsy.

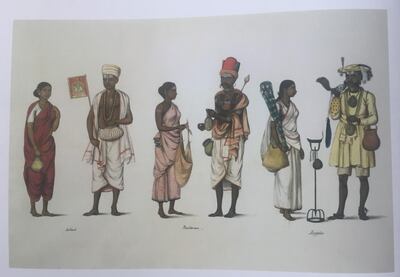

Of course, in shifting the focus of "Company" paintings to the artists, it is still possible to give credit to the patrons for influencing a shift in the preoccupations of Indian art, away from the fantastical to the naturalistic and everyday. In making Indian birds and beasts and even festivals and classes of workers (soldiers, tradesmen, ascetics) the object of their study, the Company officials democratised Indian art.

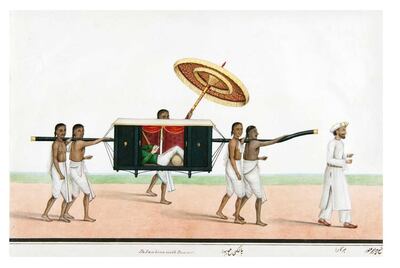

Sometimes these paintings even manage to be quietly subversive. A fine example of this tendency is in a picture of seven people (including the patron, Thomas Holroyd) made by Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya in circa 1835. Five Indian palanquin bearers, led by a servant of a higher rank, carry Holroyd on a journey while he reads in peace.

The picture makes colonial hierarchy transparent, but there is something very ambiguous, too. Headless, with his haunches wrapped around a bolster, Holroyd seems self-absorbed, but the labourers calmly return the viewer's gaze. The frame of the painting illuminates reality, the artist seems to be whispering that the palanquin shuts out.

“I have spent the past two decades writing up different aspects of a fascinating period of Indian history: the time between the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of the Raj, when colonialism had not yet acquired a fixed shape and many norms were fluid,” says Dalrymple. “To me, this exhibition is the artistic manifestation of that theme.”

Soon after this fertile intercultural encounter, Indian art would lapse into a century of mediocrity under the assault of a more prescriptive colonial gaze and practice and, simultaneously, the arrival of photography. But Forgotten Masters reminds us of the vivid and quirky pictures that still have the power to, says Dalrymple, "make us gasp."

Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company is on Amazon.ae for Dh141