The financial crisis has been a catalyst for turning bankers into budding writers, as the small but growing "cit-lit" scene in Dubai shows.

An author's biography can be a curious thing. Some are exercises in brevity while others surrender delicious details like overripe fruit falling to the ground.

Take the notes for Liza Klaussmann's new book Tigers in Red Weather, one of the highly fancied novels of the season with its cleverly constructed tale of love, lives and treachery in post-war America.

Tigers is Klaussmann's debut fiction and her biography, which adorns the book's opening page, serves up one small paragraph of notes on the author's life before dropping something of a bomb: "She is the great-granddaughter of Herman Melville." By any estimation this is quite some literary breeding.

The Art of Fielding, Chad Harbach's debut novel and a contender by almost any measure for book of the year, opts for a more concise approach. A short note, no more than two lines in length, sits on the book's closing pages and offers little more information than where the author grew up (Wisconsin), went to university (Harvard) and what he does when he's not writing novels (he co-edits a literary magazine). Little more is needed. His work, polished over more than a decade and almost universally lauded as a stunning piece of fiction, requires almost no embellishment.

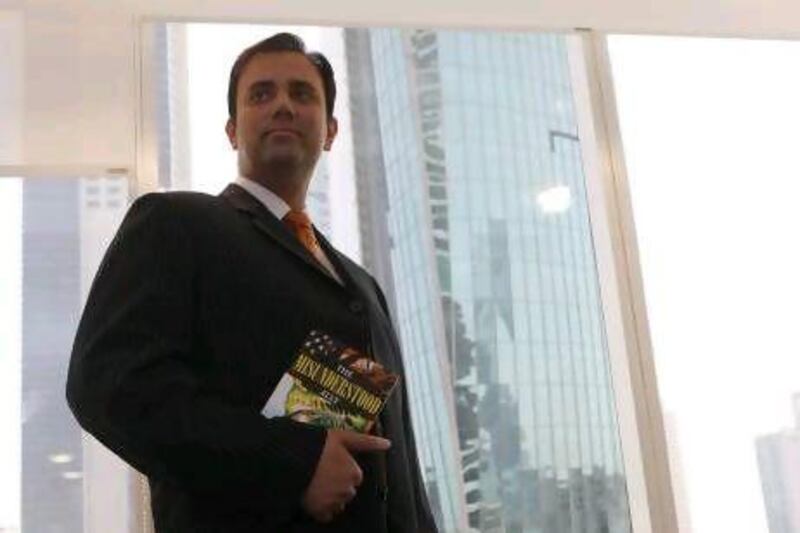

Now consider Faraz Inam. A Dubai-based expatriate and banker, his debut novel The Misunderstood Ally was published recently and its author bio yields a wonderful (for that read spectacular) curio: "Having played major roles in two blockbuster television series in Pakistan in the 1990s, Faraz now leads a humble life."

Inam is one of a small but growing community of "cit-lit" authors in the emirate. PG Bhaskar, an Indian expatriate who prefers not to name which financial institution he works for, released his first novel Jack Patel's Dubai Dreams earlier this year via Penguin India to warm notices and solid sales. He has a sequel in the works.

Meanwhile, Carlos Henrique Machado, the head of the Bank of Brazil's UAE operations, recently published The Rise of a New Order, a philosophical take on global economics.

Clearly financial crises help foster the right creative environment for bankers to blossom into budding writers and social commentators.

Inam's book, published by Strand Publishing, arrives with a sticker placed on its inside pages instructing the reader to "ignore the hiccups [and] grasp the message".

The first edition of The Misunderstood Ally is, by definition, a work in progress, but its intent is crystal clear.

The novel concerns itself with the rocky landscape of recent Pakistan-US relations and is told through the eyes of three characters.

First we meet Lt Col Dhilawar Hussain Jahangiri, commanding officer of a "crack" commando battalion of the Pakistani army deployed on the Af-Pak border. He is "strong, well-built, with deep brown intense eyes, thick black moustache cutting across a hardy facial structure". Dhil is the very picture of unflinching devotion to the military cause.

Then we encounter Mullah Baaz Jan, a "son of a Mujahid" militant who has been "fighting one enemy or another since he was an adolescent". His father, who had fought the Soviets in Afghanistan, is killed in combat when Baaz is merely a young boy, but his dying wish is that his son carries on "the family legacy of defending your honour, your family and your country. Remember, guard your homeland till the last drop of your blood. Prefer death to dishonour".

Finally, we meet Special Agent Samantha Albright, 34, who is stationed deep inside the Nevada desert in a gloomy drone operations control room. Albright is "married to her job and country", Inam tells us. "Patriotism runs in her blood. Her family heritage has been to protect America from her enemies."

Three characters, two in Pakistan, one in the US, bound together by blind loyalty. An assignment soon pushes Albright into Pakistan and the trio's separate storylines begin to circle one another.

The Misunderstood Ally is then a story of convergence and a long unravel of the complexities of international relations between the two nations, a subject that Inam talks passionately about.

"People in the West need to know the real Pakistan and people in Pakistan need to know the real intentions of the West. It has to be both ways. The media often presents a very skewed picture. This book was an endeavour to clarify certain perspectives and straighten out certain records," he says.

Towards the book's end, Albright offers an open letter to the US agency she works for. In essence, this is a thinly veiled piece of political commentary. Her prescription for a better future asserts that "violence only begets violence and hatred only begets hatred ... we cannot buy allegiance unless we listen as well".

It is a viewpoint with which the author naturally concurs: "What I've said in this book is exactly what needs to happen. First of all, stop the drone attacks. Yes, they are effective, yes, they have been able to kill militants. Yes, they have curtailed the war machinery of the terrorists, but there is a price the Americans have paid for it and that price is getting a bad name in Pakistan."

Inam moved to Dubai in 1997 but not before he had seriously considered a career in Pakistan's armed forces.

"My father was a very decorated, high-achieving fighter pilot," he says. "To me, there was no life beyond the air force and flying combat jets. Ever since my childhood their noise was music to my ears.

"But I guess fate had other plans for me. When I was about to join up, my eyesight turned weak and I couldn't be a pilot."

His wings clipped, he enrolled as a trainee aeronautical engineer, "but my heart wasn't in it," he says. "All I wanted to be was a fighter pilot. I didn't foresee a life on the ground maintaining planes while others flew. I found it very frustrating and I left."

He subsequently took a master's degree in business administration and accepted a job with a bank. But there is a twist in the path that leads from flight support to financial services.

"When I left the air force, a colleague of mine also quit and he got this offer of a role as a cadet in a [television series] about the Pakistan army. Before shooting was about to commence, he had to take up a place at an American university and he gave my name [to the producers]."

Inam auditioned and was offered a role in Sunehre Din (Golden Days) a mid-1990s 10-episode drama about a bunch of raw recruits. Broadcast on PTV, the show became a moderate hit - "the army liked it, the nation liked it," according to Inam - and the producers were commissioned to write a sequel. The follow-up, Alpha Bravo Charlie, was aired in 1998 and tracked the cadets into the field. Inam, possessed of matinée idol good looks, starred as Alpha (as in alpha male) in the 15-episode show.

He might easily have carried on acting, but just as his TV career could have reached for the skies, Inam moved to Dubai to take up a role in banking. It takes a rare man to get out when the going is good, but that's exactly what he did.

Fourteen years later, Inam says he likes his relatively "low-key life" and, more than that, he enjoys writing.

"A lot of people are encouraging me [to write a sequel]," he says. "They say that I need to write more." He is coy about the exact nature of what that second novel might consider, but it would be reasonable to expect another take on US-Pak relations.

All he will say for now is that there is "more to come". And, in every sense of the words, there will be.

Nick March is the editor of The Review.