When Aatish Taseer arrived in his native Delhi in 2007 after a long stint abroad, he returned to discover, he says, a "double shock". First, the years away - spent at Amherst College in Massachusetts, and later working for Time magazine in London - had shifted his perspective on his home city, so that even familiar sights now seemed somehow alien. On top of this, though, came the second shock: the city to which he had returned, Taseer realised, was going through a profound and inescapable transformation, a transformation that was sweeping the entire country and that rendered much of what he knew - even who he was - outdated.

In short, Taseer had returned to the supercharged, cacophonous, sometimes brutal metropolitan sprawl that is called the "New India". This month, readers have some reason to be grateful that Taseer experienced that double shock. It helped give rise to his first novel, The Temple-Goers, published in the UK by Viking, and set amid the shifting class, caste and religious terrain in contemporary middle-class Delhi.

Taseer is well placed to handle issues of Indian identity: he is the product of a brief relationship - which ended before he was born - between the Muslim Pakistani politician Salman Taseer and the well-known Sikh Indian journalist Tavleen Singh. He grew up, on the one hand, closeted inside the Indian, westward-looking upper-middle class; and on the other, mindful of an absent Pakistani father and the Muslim faith he chose to embrace despite that absence.

Taseer has already written about that background in a 2008 memoir, Stranger to History, which caused a minor storm in India, thanks to the portrait it painted of Salman, who is currently the governor of Punjab. His first novel, then, bears the weight of considerable expectation in Indian literary circles; it even comes adorned - if all that were not enough - with a cover blurb from no less a Grand Old Man of Letters than VS Naipaul (and friend of Taseer's), who calls Taseer a "young writer to watch".

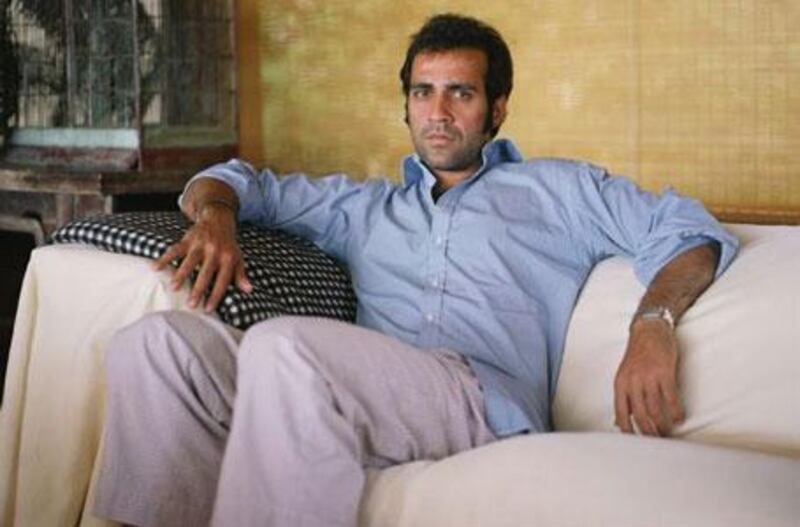

How gratifying to discover, then, that there's much more to The Temple-Goers than pre-publication hype. Taseer is in London for the UK publication, and settling down in the hushed, artfully book-strewn offices of Penguin, he is considered, thoughtful, eager to apply himself to my questions. His novel is being published upon a wave of interest in the changing India. The Temple-Goers is bound to draw comparison, foremost, with that other recent novel of the New India, the Booker Prize-winning White Tiger, which catapulted Aravind Adiga to fame in 2008.

In fact, Taseer's novel is the more fully realised of the two. We follow our narrator, also called Aatish, and also returning to Delhi after years abroad, as he befriends a brash, ambitious personal trainer called Aakash, and charts a course through the new social highs and lows of his home city. Plot comes by way of a murder, in which Aakash is implicated; but Taseer is quick to point out that this novel's real significance resides in what lies around the murder - that is, Delhi, in all its beauty and brutality - rather than in the murder tself.

There's no doubt, says Taseer, that his own return to Delhi, and the shocks it gave rise to, were the fuel that powered his writing. "Coming back to Delhi was arresting for me," he says. "First, I realised that growing up in the city I had been blind to certain aspects of it, which I now saw: the dirt, the poverty, the casual violence built into relationships between privileged people and servants.

"But there was also shock at what was changing. It was a social change that was creating kinds of people who simply didn't exist before. I grew up in India amid a class sealed away by the English language, by certain ideas of dress, and culture, and westernisation. And outside of that class were people who had very little. Now economic activity was changing that; you see all sorts of people developing their own ideas of vocation, and aspiration, and what should be theirs.

"It was, in the end, very moving to see people shrugging off wretchedness and finding a sense of hope, of self-improvement. But, of course, that process is fragile. And all of this is what makes a character like Aakash possible." It is via Aakash that Taseer can, in The Temple-Goers, investigate one of his major concerns: the falling away of old Indian identities, and the space this has left for a new kind of explicit, relentless personal self-creation.

Aakash - viciously ambitious, a Brahmin, but without material wealth - tells us repeatedly that he wants to become a new, better man. He is, he tells us, "upgrading himself". "You see this everywhere in India at the moment," says Taseer. "People's local ideas of themselves are running up against a new, bigger Indian idea, which is free of caste, free of old constraints. You might say that nothing can survive the coming of money to India at this moment."

Given all this, then, how did Taseer himself feel when he returned home in 2007? Was he liable to wonder about his own place, and identity, in the New India? "There was a certain fear of irrelevance, of removal from what India is becoming," he says. "A great feeling of having to catch up, and get over that shoddy world that I grew up in, that had a great contempt for civilisational India, for Indian dress and music. It felt as though I would have to work hard, now, to make a contribution."

While The Temple-Goers handles these questions via fiction, Taseer addressed his own identity more directly in Stranger to History: part travelogue, part memoir, part analysis of contemporary Islam. In that work, Taseer recounts his travels through a series of Muslim countries, in a quest to better understand the religion and his place in it. The emotional heart of the narrative, though, is his continuing attempt to effect reconciliation with his Pakistani father. The two did not meet until Aatish was an adult, and thereafter their relationship was troubled: Salman reportedly wrote his son a furious letter in 2005, after reading an article that Aatish had written for Prospect magazine about British Muslims, accusing him of, "invidious anti-Muslim propaganda".

Both Stranger and the new novel are surely, in part, Taseer's attempts to make sense of himself as both a Muslim and an Indian, a dual identity that Taseer has lived since childhood, long before anyone ever spoke of a "New India". "Childhood has its protections, but certainly as I grew older I felt that there was no big majority group that I could instinctively be a part of," he says. "I was something of an outsider, but I felt this could be an advantage.

"The decision to write Stranger was an attempt to understand what had happened with my father, and my family, and to understand more about how Islamic identities are changing. "It all seems so tied up with the Partition, and the attitudes that existed among my father's generation that helped bring that event about. And part of what I conclude is that if there is to be an Indian reassertion, we have to accept the hybridity of India, the multiple histories. India is a country of 180 million Muslims: it can't ignore them."

All writers of the most serious intent, though, ultimately must allow one aspect of themselves preeminence: that is, the unseen, mysterious part of their character that sends them to their desks each day to write. The process of becoming a writer is clearly a subject deeply impressed on Taseer's mind; indeed, the narrator of his novel is also a young man called Aatish Taseer, struggling with the idea, and the practicalities, of writing.

This narrator is no alter-ego, says Taseer - "he is really adrift, a very compromised character" - but it is nevertheless clear that Taseer's decision to return to India in 2007 was intimately connected with his determination to write fiction. While Stranger to History saw Taseer in search of his historic identity, this new book, it seems, has helped him forge a new one. "I had to return to India to become a writer," he says. "In London, I didn't feel the same connection to my surroundings: I couldn't look at a man on a park bench and feel something of his story. I realised that my most powerful material, and my deepest connections, were in Delhi. Also, I want to be read in India. If my writing had no impact there, I would have to change course."

Taseer says that his father has so far not responded to the book: "Perhaps when he's no longer in politics, he'll be able, on a personal level, to make a gesture, but that doesn't feel very possible at the moment." In the meantime, it seems that via his return to Delhi, and just as with his fictional creations, this young author has set about the business of self-creation. The New India needs a writer that will explain it to the world. Right now, Aatish Taseer is fashioning himself into the latest, most promising candidate.

The Temple-Goers by Aatish Taseer is published by Viking and costs Dh51 from www.amazon.co.uk.