The photographer Xenia Nikolskaya had an idea for her book after a visit to an empty museum: "I realised that absence could stand out as a theme - that it has been my theme all along."

She refers to absences in her own story: the country where she was born, the Soviet Union, which is no more, and her native city, Leningrad, now known as St Petersburg. It was there that Nikolskaya studied the art of Ancient Egypt, and this background informs her work, which expresses the viewpoint of someone who grew up surrounded by fine architecture and is able to see Egypt through western eyes. In fact, the Cairo she captures with her lens is a European city, its grandeur and dilapidation devoid of exotic oriental motifs and shown as somehow frozen in time.

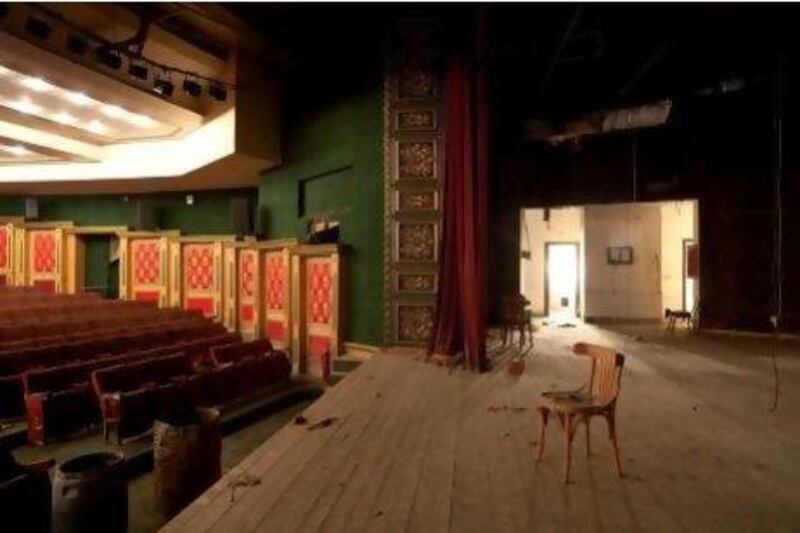

Dust contains 68 photographs taken at a few dozen locations in Egypt: Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor, Minya, Esna, Port Said and villages around the Delta. The main theme that binds her images is an empty space where past and present coexist and memories abound.

Dust is seen here as a kind of sundial that measures not diurnal rhythms but epochal ones. Some of the palaces featured in the book have been neglected for decades - a result of nationalisation and rental laws introduced by Nasser's regime. If in the photographer's home country "War to Palaces" was declared in 1917, in Egypt the revolution did not happen until 1952.

The differences between that early 20th century period and today are striking, but to see them for what they are you need to get a picture which is broader than a holiday postcard. Nikolskaya's camera provides just such a view.

The buildings pictured in the book include the Serageldin family palace in Cairo, which was built in 1902. It was intended as Kaiser Wilhelm's residence during his visits to Egypt (which were thwarted by the First World War) and bought by Serageldin Pasha afterwards.

At one time, the mansion served as the headquarters of the influential Wafd party headed by Fuad Pasha Serageldin. Since his death in 2000, the residence has been unoccupied, a belle époque monument which no one seems interested in preserving. Such are Egypt's realities; the property boom in the country has everything to do with the price of land, while the value of old houses built on it is considered negligible.

Looking at the picture of one of the palace's huge salons, with its moth-eaten carpet lit by a luxurious chandelier, you can almost smell its musty air. Another spacious room, discovered in Diwan al-Hozayen, a guesthouse in the small town of Esna, still has the furniture ordered by its owners from Paris a century ago, in line with the Europeanised nature of old Cairo. The Tiring Department Store, opened in 1912, was also envisaged as a place of Parisian chic. Now, more than half a century after it was nationalised in 1952, it is partly abandoned and partly used by squatters, mainly as tailors' workshops. The grand staircase is rotting away, surrounded by the detritus of several layers of life, all covered with dust.

Many stately homes, such as Sultana Malak Palace in Cairo's Heliopolis neighbourhood, were converted into schools after the revolution, and classroom paraphernalia is still visible in the photographs. How did pupils manage to concentrate in these opulent surroundings? Prince Said Halim's Palace, a secondary school for boys that produced a number of government officials, looks a lot more austere.

In the photo taken in 2007 there is a portrait of Hosni Mubarak above a door. "When I returned in May 2011, the room looked exactly the same as in 2007, except that Mubarak's portrait was now on the floor," remembers Nikolskaya.

In his essay accompanying the photographs, On Barak writes about "the pre-1952 cosmopolitan rainbow grey", which contributes to contemporary dust colours and lends different meanings to the substance that gave the book its title.

The state of Egypt's colonial architecture may seem static in these photographs, the idea of which is to explore spaces where life appears to have stopped half a century ago. However, since the project was started in 2006, a number of these places have been demolished. Decay and an overpopulation crisis also pose threats to the endangered urban spaces documented by Nikolskaya.

Dust was completed just before the Arab Spring stirred last year, and its message can be read as the opposite of "War to Palaces". This sentiment is strengthened by Barak's afterword, which finishes on an optimistic note with the hope of a new Egypt emerging from under the layers of dust accumulated here.

Anna Aslanyan is a freelance writer and co-editor of 3:AM magazine.